Katherine frowned when she read that part of Wolsey’s account, calculating that Henry would hire the emperor at an inflated amount and would thus have to pay an ally who had promised to come at his own expense for a mercenary army. She recognized at once the double-dealing that had characterized this campaign from the start. But at least it would mean that the emperor was with Henry in his first battle, and Katherine knew that she could rely on the experienced older man to keep the impulsive young king safe.

On the advice of Maximilian, the English army laid siege to Thérouanne—a town which the Holy Roman Emperor had long desired, but of no tactical value to England—and Henry, safely distanced from the short-range guns on the walls of the little town, walked alone through his camp at midnight, spoke comforting words to the soldiers on watch, and was allowed to fire his first cannon.

The Scots, who had been waiting only until England was defenseless, with king and army in France, declared war against the English and started their own march south. Wolsey wrote with alarm to Katherine, asking her if she needed the return of some of Henry’s troops to face this new threat. Katherine replied that she thought she could defend against a border skirmish, and started a fresh muster of troops from every town in the country, using the lists she had already prepared.

She commanded the assembly of the London militia and went out in her armor, on her white horse, to inspect them before they started their march north.

I look at myself in the mirror as my ladies-in-waiting tie on my breastplate, and my maid-in-waiting holds my helmet. I see the unhappiness in their faces, the way the silly maid holds the helmet as if it is too heavy for her, as if none of this should be happening, as if I were not born for this moment: now. The moment of my destiny.

I draw a silent breath. I look so like my mother in my armor that it could be her reflection in the mirror, standing so still and proud, with her hair caught back from her face and her eyes shining as bright as the burnished gilt on her breastplate; alive at the prospect of battle, gleaming with joy at her confidence in victory.

“Are you not afraid?” María de Salinas asks me quietly.

“No.” I speak the truth. “I have spent all my life waiting for this moment. I am a queen, and the daughter of a queen who had to fight for her country. I have come to this, my own country, at the very moment that it needs me. This is not a time for a queen who wants to sit on her throne and award prizes for jousting. This is a time for a queen who has the heart and stomach of a man. I am that queen. I shall ride out with my army.”

There is a little flurry of dismay. “Ride out?” “But not north?” “Parade them, but surely not ride with them?” “But isn’t it dangerous?”

I reach for my helmet. “I shall ride with them north to meet the Scots. And if the Scots break through, I shall fight them. And when I take the field against them I shall be there until I defeat them.”

“But what about us?”

I smile at the women. “Three of you will come with me to bear me company and the rest of you will stay here,” I say firmly. “Those behind will continue to make banners and prepare bandages and send them on to me. You will keep good order,” I say firmly. “Those who come with me will behave as soldiers in the field. I will have no complaints.”

There is an outburst of dismay, which I avoid by heading for the door. “María and Margaret, you shall come with me now,” I say.

The troops are drawn up before the palace. I ride slowly down the lines, letting my eyes rest on one face and then another. I have seen my father do this, and my mother. My father told me that every soldier should know that he is valued, should know that he has been seen as an individual man on parade, should feel himself to be an essential part of the body of the army. I want them to be sure that I have seen them, seen every man, that I know them. I want them to know me. When I have ridden past every single one of the five hundred, I go to the front of the army and I take off my helmet so that they can see my face. I am not like a Spanish princess now, with my hair hidden and my face veiled. I am a bareheaded, barefaced English queen. I raise my voice so that every one of them can hear me.

“Men of England,” I say. “You and I will go together to fight the Scots, and neither of us will falter nor fail. We will not turn back until they have turned back. We will not rest until they are dead. Together we will defeat them, for we do the work of heaven. This is not a quarrel of our making; this is a wicked invasion by James of Scotland, breaking his own treaty, insulting his own English wife. An ungodly invasion condemned by the Pope himself, an invasion against the order of God. He has planned this for years. He has waited, like a coward, thinking to find us weak. But he is mistaken, for we are powerful now. We will defeat him, this heretic king. We will win. I can assure you of this because I know God’s will in this matter. He is with us. And you can be sure that God’s hand is always over men who fight for their homes.”

There is a great roar of approval and I turn and smile to one side, and then the other, so that they can all see my pleasure in their courage. So that they can all see that I am not afraid.

“Good. Forward march,” I say simply to the commander at my side and the army turns and marches out of the parade ground.

As Katherine’s first army of defense marched north under the Earl of Surrey, gathering men as they went, the messengers rode desperately south to London to bring her the news she had been expecting. James’s army had crossed the Scottish border and was advancing through the rolling hills of the border country, recruiting soldiers and stealing food as they went.

“A border raid?” Katherine asked, knowing it would not be.

The man shook his head. “My lord told me to tell you that the French king has promised the Scots king that he will recognize him if he wins this battle against us.”

“Recognize him? As what?”

“As King of England.”

He expected her to cry out in indignation or in fear, but she merely nodded, as if it were something else to consider.

“How many men?” Katherine demanded of the messenger.

He shook his head. “I can’t say for certain.”

“How many do you think?”

He looked at the queen, saw the sharp anxiety in her eyes, and hesitated.

“Tell me the truth!”

“I am afraid sixty thousand, Your Grace, perhaps more.”

“How many more? Perhaps?”

Again he paused. She rose from her chair and went to the window. “Please, tell me what you think,” she said. “You do me no service if, thanks to you, trying to spare me distress, I go out with an army and find before me an enemy in greater force than I expected.”

“One hundred thousand, I would think,” he said quietly.

He expected her to gasp in horror but when he looked at her she was smiling. “Oh, I’m not afraid of that.”

“Not afraid of one hundred thousand Scots?” he demanded.

“I’ve seen worse,” she said.

I know now that I am ready. The Scots are pouring over the border, in their full power. They have captured the northern castles with derisive ease; the flower of the English command and the best men are overseas in France. The French king thinks to defeat us with the Scots, in our own lands, while our masking army rides around northern France and makes pretty gestures. My moment is now. It is up to me, and the men who are left. I order the royal standards and banners from the great wardrobe. Flown at the head of the army the royal standards show that the King of England is on the battlefield. That will be me.

“You will never ride under the royal standard?” one of my ladies queries.

“Who else?”

“It should be the king.”

“The king is fighting the French. I shall fight the Scots.”

“Your Grace, a queen cannot take the king’s standard and ride out.”

I smile at her. I am not pretending to confidence: I truly know that this is the moment for which I have waited all my life. I promised Arthur I could be a queen in armor, and now I am. “A queen can ride under a king’s standard, if she thinks she can win.”

I summon the remaining troops: these will be my force. I plan to parade them in battle order, but there are more comments.

“You will never ride at their head?”

“Where would you want me to ride?”

“Your Grace, perhaps you should not be there at all?”

“I am their commander in chief,” I say simply. “You must not think of me as a queen who stays at home, influences policy by stealth, and bullies her children. I am a queen who rules as my mother did. When my country is in danger, I am in danger. When my country is triumphant, as we will be, it is my triumph.”

“But what if…?” The lady-in-waiting is silenced by one hard look from me.

“I am not a fool. I have planned for defeat,” I tell her. “A good commander always speaks of victory and yet has a plan for defeat. I know exactly where I shall fall back, and I know exactly where I shall regroup, and I know exactly where I shall join battle again, and if I fail there, I know where I shall regroup again. I did not wait long years for this throne to see the King of Scotland and that fool Margaret take it from me.”

Katherine’s men, all forty thousand of them, straggled along the road behind the royal guard, weighed down by their weapons and sacks of food in the late-summer sunshine. Katherine, at the head of the train, rode her white horse where everyone could see her, with the royal standard over her head, so that the men should know her now, on the march, and recognize her later, in battle. Twice a day she rode down the length of the line with a word of encouragement for everyone who was scuffing along in the rear, choking with the dust from the forward wagons. She kept monastic hours, rising at dawn to hear Mass, taking Communion at noon, and going to bed at dusk, waking at midnight to say her prayers for the safety of the realm, for the safety of the king, and for herself.

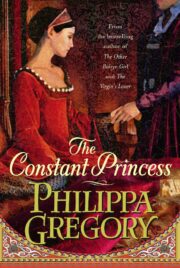

"The Constant Princess" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Constant Princess". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Constant Princess" друзьям в соцсетях.