He asked about my family, so I related how my mother was the religious one, how Uma claimed to be an agnostic yet went to the temple regularly, how my father, at the opposite end of the spectrum, still ranted, all these years later, against replacing the secular “Bombay” (which he was only too eager to explain came from the Portuguese for “good bay”) with the goddess-inspired name “Mumbai.” “As for me, I’m somewhere in between—some days I call it Bombay, other days, Mumbai; some days I pray, other days, I don’t believe.”

“A probabilistic approach—how very apt. A statistician through and through, I see.”

“Not quite. One day I’ll tell you about my disastrous management degree.”

The sun had begun to turn the waves orange by the time we left the beach. Perhaps it was the imminence of the 123 bus whisking me away, like it had every evening this week, leaving me again unfulfilled about Karun’s romantic background. But as we walked to the bus stop, the question eating away at my mind abruptly broke free. “Did you leave behind a girlfriend back in Delhi, Karun?” I blurted out, then stared at the ground, mortified.

“No,” he replied. I couldn’t tell if he’d taken offense.

I should have stopped, but something about the lurid pinkness of the evening sky goaded me on. “I’m sure you must have had many girlfriends before, though.” This time, I looked up to gauge his reaction.

His face fell, as if I’d exposed a hidden inadequacy. “No, not really.” He looked away, blushing. “I’ve never had a girlfriend.”

Was that it, then? A past so uncomplicated that it could be summarized so succinctly? And why not? The history of my own romantic life was just as concise, containing a single entry, that too uncertain: Karun.

Something opened inside me, much deeper than the girlish fantasies I had indulged in until now. I felt a swell of empathy towards him—at our shared lack of worldliness, at the inexperience that linked us, at the crushing mantle of studiousness he must have labored under as well. Sweat dampened his armpits, the hair at his temples looked inexpertly trimmed, a dark ring ran along the inside of his collar. I found each detail endearing, reassuring—the less perfect he was, the less I had to be. “I’ve never had anyone either,” I said, taking the palm of his hand in mine without thinking. “I’m glad you moved here from Delhi.”

He didn’t say anything, but didn’t withdraw his hand either. Behind us, the sun smeared and flattened at the horizon, losing all its fire as it sank. I didn’t look at him when the bus came, not trusting my face to hide the closeness I felt. Instead, I quickly squeezed his palm and clambered up the steps to the top deck. As the bus pulled away, I looked through the rear window to watch him weave through the hawkers on the pavement, the bag with his swim things swinging by its sash at his side.

THE BEATING HAS stopped for the moment. The victim lies crumpled in a corner of the basement—from his groans I know he is still alive. The Khakis stand around, discussing what more to do to him. There is not much else to occupy them in the basement, so I know they will come up with something. A few of the children, including the one interested in my pomegranate, advance cautiously to the victim. One of them spits at him, another bounces a rock off his back. “Beat the sisterfucker,” the woman next to me urges.

A doctor tries to get through, but the Khakis block his path. Nobody touches him, they snarl. “Do you hear, nobody touches the sisterfucker,” the woman next to me calls out. The doctor returns to his group. At least one of us tried, even if it wasn’t me, I think guiltily to myself.

Someone finds a rope. I know what comes next, and feel sick that I’m going to just sit there and let it happen. I don’t want to look, but my gaze remains transfixed. At the rope being knotted into a noose, at the other end being slung over a hook in the ceiling (so conveniently placed—was someone anticipating a hanging?). The man protests unintelligibly as the Khakis drag him from the corner by his hair. I catch a glimpse of his face, it seems to have caved in—only a mass of red remains where one might have seen a nose, a mouth.

He screams as they sling the noose around his head and begin to hoist him up. His feet leave the ground, and the screams turn to gurgles. His hands claw at his throat, then find the rope and begin to draw his body up it, so he doesn’t choke.

“You fool, you forgot to tie his hands,” says one of the Khakis pulling on the rope. The body, released, hits the ground with a thud.

They look around for more rope. The woman next to me produces some cord from her bag, “for the sisterfucker,” but it’s too flimsy. “Use his belt,” someone shouts, but he isn’t wearing one. So they rip off his pants, and for good measure, his underwear as well.

As they tie his hands with his trousers, one of them starts cursing. Apparently, the victim’s not Muslim—he isn’t circumcised. They decide to carry him back to his corner, where they prop him up against the wall. The noose still dangles from his neck. A Khaki tries shaking him awake to offer him a cigarette.

BY THE END OF MAY, I knew I had learnt to swim as well as I ever would, at least in this lifetime. I could make it to the deep end of the pool, splashing along at Karun’s side, using a medley of movements that bastardized both the breast stroke and the free style. Like someone learning a foreign language without concern for pronunciation or grammar, my swimming was free of grace or fluidity—I had found the crudest way of getting across without sinking.

We went to the beach after almost every lesson, eating our way through all the snacks (except the “cholera special” fruit plate). Sometimes, we sat on the sand to admire the sunset—every third day, we watched the sculptor embark on a new carving, tossing a five-rupee coin on the cloth he spread out on the sand. Karun would elaborate on his father’s own unique interpretation of the Trimurti—how Vishnu, with his sunny disposition, represented the dynamism to make things work, while Shiva personified introspection, solitude, the tendency to withdraw from life. Which left the rest of nature’s attributes for Devi to embody: since she received the power to create, she was the most versatile. “Baji said one of the three usually predominates in a person’s personality. He’d see a child full of fun and frolic, or mischievous like Krishna, and tell its parents, ‘You’ve got a lively little Vishnu there.’ Or call someone very dreamy, lost in his or her own little world, ‘a real Shiva.’” According to his baji, people went through the world searching for their complements. “A Shiva needs a Vishnu or Devi to pull him out of his shell so he can engage with the world, a Devi depends on a Shiva or Vishnu to provide her with seed, and poor Vishnu must constantly run after Shiva and Devi to ensure the universe keeps going. More than just pairing up, though, the universe needs the union of all three. When Shiva, Vishnu, and Devi find each other, when they all coalesce as one, then and only then is the circuit of the universe complete, its true power unleashed.”

“So were you his little Vishnu?”

“No, I guess I was more Shiva—too much the loner, even when little. The Vishnu in our trinity was definitely Baji himself—always on the move, always keeping my mother and me going. We’d enact out my favorite myth, where Vishnu takes the form of an enchantress to seduce Shiva into the swing of things. I’d pretend to meditate, but then roll around laughing the minute Baji sashayed by, draped in a sari.”

Despite these languorous evenings, our courtship didn’t advance to anything more formal, like a restaurant meal or theater outing. Karun and I did return to Juhu with Uma and Anoop, to test my new aquatic skills in the sea (a “double date,” Uma called it). We chose a Sunday, the most crowded time of the week, when a mass of humanity, dark and roiling, covered the beach. An ongoing battle raged against the sea, which churned at its most ferocious, the monsoon being only a week away.

We abandoned the idea of fighting the crowds and the thundering waves in favor of trying to sneak into the outdoor swimming pool at the Indica. Krishan Patel, a Silicon Valley–returned microchip entrepreneur, had announced the hotel as a grand celebration of India’s triumph in the new world order, an “awe-inspiring homage” that would showcase the entire history and roster of accomplishments of his country of birth. The exterior reflected this—turrets and crenellated parapets evoked Mughal forts and palaces, balconies with lace-like Rajput carvings floated from the sides, and the futuristic glass and steel penthouse suites even sported a few intricately chiseled gopurams, rising above doorways in the Vijaynagar style. The idea of the sari-clad Statue of Liberty replica was to beckon to the West, Patel said, rather than look towards it, India being the new beacon of achievement, of opportunity.

Unfortunately, the opening did not go smoothly. Critics ripped into the fusion of architectural and décor styles (“a schizophrenic monstrosity,” “Shah Jehan goes to the circus,” “more gaudiness and less taste than at a Gujarati wedding”), the computers for the much-hyped laser tribute to desi IT advances kept catching on fire (literally bursting into flame), and a near-riot broke out at the “Stomach of India” restaurant when Jain tourists found a chicken bone in their vegetable biryani. To top it off, Patel had apparently gone bankrupt during construction—rumor had it that the Indica had been bought up and completed by the Chinese.

None of this turned out to matter. The hotel proved such a success that already, an annex was being built in the lot behind. A busy stream of people headed to the pool through the glass doors of the atrium today. Uma strode boldly along, taking Anoop on her arm as well, but the guard challenged Karun and me to produce our guest cards, and we all ended up in the Sensex Bar, drinking coffee.

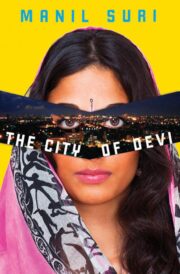

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.