BY THE TIME I got to the water’s edge, Uma had already entered the waves and was cavorting with Anoop some distance away. Unlike her, I hadn’t brought a swimsuit, so I pulled my salwaar up my legs as high as the openings would allow, and wrapped my dupatta around my waist. Karun stood with his back to the sun, the red of his shorts flaring in the tide. “I can only come in up to my knees,” I called out to him, but the wind blew my words away.

I raised my hand against the sky to shade my eyes, but the glare from the water was too strong to make out his face. Waves broke against him, their foam encircled his waist. He stood where he was, his darkened form emerging like the statue of a deity from the sea. Didn’t they used to say a woman’s husband was her god, her swami, didn’t people still believe a spouse embodied divinity? Was I standing on the sands on the floor of Karun’s temple, were those blessings that rippled across the water from him to me?

I waded in deeper. Coconuts bobbed and rolled on the water surface, their husks black from days at sea. A wave brought in a garland of brown marigold and wrapped it around my legs. I bent down to untangle it and watched it float away towards shore. Who had offered it to the sea, and why? Had someone been born, had someone expired, was it part of a marriage ceremony? A fisherman and his bride maybe, come to solicit a blessing from Mumbadevi? The goddess after whom the city was named, who some believed made her abode in this very sea?

I waved to Karun, but he still did not acknowledge me. I could see now that he’d folded his arms across his chest, holding them close to his body as if guarding against a chill. A chill which couldn’t exist, the sea being as warm as bathwater. “Karun,” I called, waving again, and this time, he waved back.

But he did not come to me. I stood there, wondering whether to venture in deeper. The water had already crept up my salwaar to my waist—any further, and it might begin the climb to my chest. I imagined the ride back home on the train, my clothes sticking to my skin, the outrage on my mother’s face as men crowded around to leer. I turned, half expecting her to wade in after me, all thoughts of her own clothes getting wet lost in the attempt to rescue me from shame.

Nobody stopped me. A group of children paddled by on a raft, in pursuit of a boy holding a basketball high above his head. A fully dressed woman swam purposefully through the waves, the folds of her sari ballooning around her like the whorls of a jellyfish. On the shore, I could make out the red and white segments of the umbrella under which my mother slept. In the distance, the figure of a lone child emerged from the smiling mouth of Mickey Mouse and slid down his inflated tongue.

I took another step in. A large wave, its head irate and foamy, slammed into my groin. I staggered, and for an instant wondered if I should fall. Surely then Karun would have to run to me. I would be drenched, but the distance between us would be dissolved. Would he reach into the water and pull me up in his arms?

Before I could further evaluate this ploy, he came sloshing up to me. “Do you like to swim? It’s something I’ve loved ever since my teens.”

Could this be the criterion he’d set for a spouse—someone aquatically adept? I thought back to all those wasted swimming sessions at school, spent splashing around in the shallow end of the pool. “I never did learn.” The confession brought with it that sinking feeling of having skipped over a topic, only to find it on the test.

Karun contemplated me silently. “I could teach you,” he finally said, and I felt myself flush. Perhaps he didn’t mean more than his offer stated. But how could he not see what an intimate invitation this was to extend to an unmarried woman my age? Fortunately, a wave thundered down upon us to hide the redness of my face. I fell over backwards, felt the sea squeeze into my ears and nose, tasted salt at the back of my throat. For an instant I was completely submerged—sand swept into my sleeves and packed itself in my hair. How would I face my mother now? I wondered, imagining the men on the train ogling me in my waterlogged clothes.

The water cleared to reveal Karun’s face. The wave had knocked him over as well, his body covered mine. He tried to disentangle himself, but stumbled, and fell face forward into my chest. The tip of his nose plunged into my bosom, as if trying to sniff out some scent, dark and hidden, from deep between my breasts.

He sprang back up before I could react. “Sorry,” he stammered, staring pointedly away.

A volley of small waves whitened the water around our knees. He looked so perturbed, I wanted to soothe his hand in mine. “It was the tide. It’s too strong.” He nodded but did not turn. “Have you taught many people before how to swim?”

He raised his head and regarded me without speaking. Was he having second thoughts—could our physical contact have made him change his mind?

Perhaps Mumbadevi herself sent in the next wave to set things right. She didn’t topple me, not quite, just made me stagger and thrust my hand out blindly through the foam. She knew Karun would grab for it by instinct, hold on to it so I didn’t fall. Prudently, she withdrew this time, without forcing an embrace like in her clumsy previous attempt.

“The tide’s a lot less rough farther out,” he said, as I tried to wipe the salt water off my eyes. “They’re just ripples there—they only swell into waves as they near the shore.”

“It must be very deep.”

“The drop is quite gradual, actually. I can take you. You just have to hold on.”

Somewhere from the beach came the call of a man selling shaved ice. “Gola, gola,” he cried, “limbu, pineapple, ras-bhari.” I pictured the two of us sharing a raspberry gola, taking turns to suck the syrup from the ice. The line between Karun’s lips getting darker with each intake, the same intense crimson as mine. When the ice was gone and only the stick remained, I would press together our lips. Not to kiss, but to see how the curves fit, his crimson aligned against mine. For who was to say this wasn’t the match that really mattered, more than horoscopes and birth charts and palm lines? That the compatibility between two souls couldn’t be reduced to this question of geometry, of mathematics?

“We don’t have to go if you’re afraid.”

In truth, I was a little nervous of water, had been since my school swimming pool days. But the iceman was far away on shore, my experiment there would have to wait. “As long as you think it’s safe.”

“It is,” he said. Then he took my hand and started swimming backwards towards the horizon, pulling me along into the ocean, past the coconuts and the garlands, past the woman with the billowing sari and the children diving into the breakers, past the point I could hear the iceman’s call or touch sand with my feet, until the waves were shorn of their foamy manes and the sea swelled silently against our chins.

2

A SCUFFLE BREAKS OUT IN A CORNER OF THE BASEMENT. THE Khakis have accused a man of being Muslim, they proceed to beat him. I see a doctor swing his stethoscope above his head like a whip, two women in nurse’s uniforms wield umbrellas and try to elbow their way in. Even the woman next to me does her share, hurling insults at the victim across the room. “Son of a pig sisterfucker,” she says, and aims a stream of spit in the direction of the commotion.

Although aware of the city’s partition along religious lines, I’ve never witnessed the hatred fueled by this division firsthand. I now understand the advice my watchman tried to impress upon me so emphatically this morning: only the very brave or the very foolish venture into the wrong area of town anymore. Still, this is a hospital, I feel like shouting—even if it lies in a Hindu sector, does that mean the only treatment administered to Muslims is this kind of battering? Had we been at Masina hospital in Byculla, would I be the one meted out such violent medicine instead?

They claimed this could never happen. Bombay was too cosmopolitan, its population too diverse, its communities too interdependent to ever become another Beirut or Belfast. “Just think of the financial give-and-take alone,” my father would say. “Without everyone’s cooperation the economy would simply dry up.” He’d point to the language riots of the fifties, the communal campaigns of the sixties and seventies, the waves of bomb blasts since the early nineties that blew up hundreds as they sat in trains or buses or offices. “Bring on whatever havoc you will—the city will remain united even if the rest of the country splits apart.”

For a long time, he was right—even the Pakistani guerrilla attack in 2008 seemed to only increase the city’s cohesive resolve. “See these people holding hands?” he asked, at the candlelight vigil outside the still-smoking Taj Hotel. “They’re neither Hindus nor Muslims, but citizens of Bombay first.”

I try to summon that spirit of unity now as I listen to the screams of the man being pummeled. How could we have fallen so far so quickly? Especially when Mumbai was on the verge of becoming such a world-class metropolis? The dazzle and architectural chic of the Bandra-Worli Sea Link, the City of Devi campaign that would fast-track us to international fame—who could have predicted that the seeds of our doom lay therein? I try not to loop once more through the arc of events that’s led us to our ravaged state, try to tune out the muffled crunch of metal meeting bone through cloth and skin. I must become more hard-hearted for survival’s sake, learn to channel my mind back to the memory of more pleasant days.

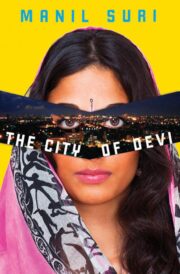

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.