MY MOTHER’S REACTION to the swimming lessons from Karun disappointed me. I had hoped for tantrums, for drama, perhaps even a curfew, like my parents tried to enforce on Uma when she first started spending evenings late with Anoop. “It looks like a pillowcase,” my mother declared upon seeing me in my high school swimsuit. “Can’t you get something that better shows off your figure?” I realized then how old thirty-one was, how dire my prospects must seem to her.

So that weekend, Uma helped me pick something suitably revealing from a boutique in Colaba. Its blue and white stripes stretched over my breasts to remind me of yacht sails, of beach umbrellas. I imagined emerging from the showers like a Danielle Steel vixen, the water trickling down my neck and beading on my bosom as I walked seductively towards Karun. But at the pool, my courage evaporated as soon as I left the locker room. I covered myself with my arms as best as I could and scurried across to the shallow end.

Karun stood against the swimming pool wall, his knees bent, so that the water lapped against his throat. Sunlight set his body ablaze, the tiles burned blue and bright all around him, ripples spread glittering towards and away from his chin. “Come in,” he said. “The temperature’s nice.” Although his gaze flickered over my swimsuit, he didn’t comment on my new nautically themed breasts.

As usual, our bodies hardly touched. Each time I thought they would, he managed to skirt contact without making it look like a purposeful move. Today, we worked on the dreaded amphibian kick—he demonstrated the entire sequence without even grazing my leg. Was it just shyness that kept us so chastely separated, or lack of interest on his part? Where was Mumbadevi to transport me back into his arms?

“You worry too much about sinking,” Karun announced. “Let’s try it with a life ring around your waist.”

For a while I paddled around like some hapless circus animal stuck into a prop for an aquatic trick. Finally, after slipping out for the fifth time, I voiced the obvious. “Don’t you think it would be better if you kept me afloat with your arms?”

He touched me then, setting his palms against my stomach, sparking off all the right chemicals in my brain. I sensed a delicacy in the way he handled me, as if, made of china, I might drop to the bottom of the pool and break. This decorum worried me—how distressing if the only outcome of these lessons turned out to be my learning to swim.

We walked over to the beach at Chowpatty afterwards. I’d waited in vain each evening for Karun to take my hand—he didn’t do so today, either. More than hand-holding, though, I felt the greatest longing towards the couples sharing snacks at the food stalls. Swimming left me ravenous, but it seemed too forward to suggest we split a bhel puri or dosa.

“Should we get something to eat?” Karun asked, and I almost swooned. I steered him to the vegetable sandwiches—the safest, I figured, given the staidness he projected. “I know from the picnic how much your family adores sandwiches,” he said. “But would you mind if we tried something spicier, like dosas?”

The dosas tasted so good with their fiery coconut chutney that we ordered a second round. I boldly suggested we finish with kulfi, even deciding on the flavors—mango and saffron. The kulfiwalla rolled the frozen metal cones deftly between his palms to loosen the ice cream inside. He unmolded them on the same leaf for us to share, the intimacy of which prospect made us both blush.

We strolled along the beach, scooping up bites of the kulfi from the leaf with our plastic spoons. Karun ate more of the saffron, leaving the mango for me, since it tasted better. “I haven’t had kulfi on the beach like this in ages, not since my college years in Bombay.” He shook his head when I asked him if he’d kept in touch with his friends from then. “They’ve all moved away—things never remain the same.”

Of course, I really wanted to ask him about girlfriends—here in Bombay, or back in Delhi, or even while growing up in Karnal. But I couldn’t formulate a subtle enough way to pose the question. In three days, I’d ferreted out almost no useful information—Uma and my mother were appalled at my lack of data mining skills. We talked about such neutral topics like his research in particle astrophysics (studying quark densities to understand the origins of the universe) and the reason I chose statistics (all those exotic-sounding curves, from Gaussian to gamma to chi, I sheepishly confessed, drew me in).

As I tried yet again to think of some artfully camouflaged way of bringing up the girlfriend question, Karun stopped. “Look, it’s the Trimurti.” He pointed to a three-headed tableau in the sand. The sculptor had already completed two of the faces and was preparing to carve the third. “Vishnu the caretaker and Shiva the destroyer—my father had an interesting take on who should occupy the final spot in the trinity.”

Wary that the evening’s investigative opportunities might get sidetracked again, I didn’t respond. But Karun pressed on. “Go ahead, take a guess—who do you think should rightfully be called the creator of the universe?”

“Not Brahma? Isn’t he the one who blows everything out in a single breath?”

“Ah, but creation comes from the womb, not the mouth—a simple matter of anatomy, as my baji would say. So logically, the true third should be the mother goddess, Devi.”

“I think your baji was just pulling your leg. It’s Vishnu, Shiva, Brahma, everyone agrees.”

“Not everyone. Majumdar was one of the first to point out that Brahma’s inclusion wasn’t quite so successful, and other scholars have agreed. The fact is, few worship Brahma—not compared to the millions of Devi followers. Just think of all the temples she has in even the remotest spots of the country.”

“So we should tell sculptors everywhere to forget about Brahma, to compose their Trimurtis based on a popularity contest?”

Karun laughed. “Absolutely. In a way, it’s already happened. All those paintings and statues you’ve probably seen—it’s always Shiva fused with Vishnu, or Devi fused with Shiva, or half Vishnu, half Devi. They’re always trying to complete themselves, Baji said—find the attributes they’re missing, the ones they crave. Brahma rarely gets invited to enjoy such intimate couplings.”

Sensing the conversation veering away on a tangent, I tried to turn things to my advantage by squeezing out more information about Karun’s family. “Was he quite religious, your baji?”

“By most standards, yes, but more than religion, I think he loved mythology. He’d relate a legend to me every night—the sea of milk that churned up jewels, the giant fish Matsya who saved mankind during the flood. It was such a magical way to understand the world.”

“But not a very scientific one—not the best training for a physicist.”

“Actually, he often added a scientific twist. Like relating the flood in Matsya’s story to actual periods on earth when the oceans rose. Or using Vishnu’s incarnations—first fish, then reptile, then mammal, then man, to tell me about evolution—I still remember that.”

“So he was a scientist as well?”

“No, not really, though he probably would have made an excellent one if he’d received the opportunity. Family problems forced him to leave college after the first year—he ended up as a purchaser for a construction firm. But he never lost his interest in books, his curiosity—he dabbled in so many things. Gardening, for one—we actually had a pomegranate tree growing right there on our balcony. Mythology and science were his favorites, though—he found all sorts of colorful ways to combine them. For instance, he’d say that three was the magic number of the universe, its most intrinsic configuration—not just because of the triad of primary colors or our three space dimensions, but also because of all the trinities in different religions, especially the Trimurti. He was convinced that everything derives from the basic building blocks of Vishnu, Shiva, Devi. Pseudoscience you might say, or mystical nonsense, even—but it had a charming ambitiousness to it, sort of a layman’s Grand Unified Theory. Perhaps that’s why I went into physics—to get the training Baji never received.”

Brahma had begun to emerge from the sand, and with him, a fundamental question arose in my mind. “And what about you—do you believe at all? The religion, the mythology—did you inherit any of that from your baji?”

Karun watched the sculptor pat one of Brahma’s eyebrows in place. “When I was a child, I accompanied Baji in everything. The incense, the temples, the praying—it was such an essential part of my life. But things began to change soon after he died—I began to question more, notice contradictions I couldn’t reconcile. Now it would be hard to feel the same, even if I tried. Take this carving. I know people might worship it as the Trimurti but I can’t help think of the individual grains of sand of which it is made. Of the multitudes of molecules and atoms and electrons in each grain, the drama being performed invisibly at the levels we don’t see. A trinity of gods emerging from the sand is one way of interpreting the universe’s wonders, but perhaps other, more subtle ways can explain it all more usefully.”

“So you’re an atheist, then?”

“I suppose I fit that old physicist cliché of equating God with the laws of the universe—who said it first, Einstein? Baji’s myths, I know, will never play out before my eyes, but as metaphor, they’re still enchanting. Devi emerging resplendently from the sea, these sand carvings miraculously coming to life, even Baji’s obsession with the number three. Which the universe seems to endorse, he’d be pleased to know—there are exactly three generations of fundamental particles that make up everything.”

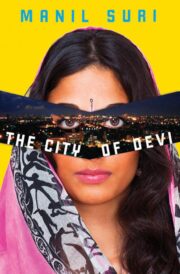

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.