Except, that is, for G6AQR—“Mr. Cheerio,” as Vincent calls him. “He must have an encyclopedia just on Diu right next to him. Dozens of questions—about street intersections, museum idols, even the number of cannons at the fort, to check on me. I’ve never seen a ham so suspicious—all to confirm I wasn’t some other nationality.”

To Vincent’s chagrin, Mr. Cheerio refuses to reciprocate. “He claims to be a former BBC broadcaster, says it’s too dangerous to announce where he’s located. For all I know, he could be a jihadi hatching a terrorist plot from somewhere in Iran or Yemen.”

What Mr. Cheerio does share is news about the rest of the world. The most serious loss of life, wide swathes of it, has resulted from nuclear plant explosions. “Two confirmed reactors in each of Canada and France—a near-affirmative on at least a dozen more.” The cyber viruses have ravaged the more computerized countries of the globe, incinerating power lines, transformers, anything plugged in, down to kitchen blenders and laptops. “They say the plague was bad, but this epidemic is worse. Enormous electric surges in alternating directions—that’s how the basic strains work. No easy way to repair the grid—things will continue like this for months.”

Mr. Cheerio does have some cheerier news, however. “Don’t believe all those lids babbling about EMPs—or for that matter, tsunamis or earthquakes or locusts. As for the terrorism, it’s pretty much faded. Dirty bombs have become superfluous, the jihadis retreated to their caves.”

He’s philosophical about the India-Pakistan exchange. “It was time. Too much tension had built up. Not just in your corner, but the world over. For quite long, the mere prospect was deterrence enough. But eventually the memory fades, there arises the need to see and smell and taste blood.” He points out that the bombings immediately cut off combat not only between the two countries, but across the globe. “It stopped World War III in its tracks—hopefully, for at least a few decades to come. Even the civil war insurgents in Pakistan have forgotten what they were fighting for.”

So far, although we can’t verify any of his claims, Mr. Cheerio has spoken in the measured, authoritative voice of a seer, an oracle. But now he starts spouting a mess of allegations, for which he freely admits he has little or no evidence. “It all comes down to the Chinese—not just the computer viruses but also the scare of October nineteenth. Operations meant to blow off steam, kick up the sand, take their rivals down a few notches.” He believes it had to be the Youth Democratic League. “They recently executed all the group’s hothead leaders according to my Hong Kong old man. It might be a while before they go the liberalization route again—democracy isn’t for the fainthearted.”

Like a conspiracy theory buff, Mr. Cheerio has an answer for everything, even for the facts that don’t quite fit comfortably. Since jihadis appear to have been involved, the young Chinese renegades had doubtlessly forged links with Islamic terrorists. The September 11 anniversary date must have been chosen, quite plainly, to draw suspicion away. He believes the Chinese had been funneling in support to both the HRM and the Limbus to keep India in a state of ferment. “Maybe even with their government’s blessing. At least until things spun out of control, until the nukes got wheeled out and the viruses went crazy.”

At first, my inclination is to dismiss everything—Mr. Cheerio seems to suffer from a particularly virulent case of Yellow Peril Fever. But then I start wondering. Ascribing sophisticated cyber sabotage techniques to jihadi organizations like Al Qaeda always seemed a stretch. And the communiqués that contained such accurate information of attacks coordinated with Pakistan—who else but the Chinese could supply such details? Come to think of it, didn’t Rahim mention something about Chinese guests visiting his guesthouse? And weren’t there reports that when the Indica faced bankruptcy, a Chinese company had saved it? Could they be the puppeteers who forbade its bombing, the protectors Sarahan refused to name?

“Let me tell you how I think the nuclear exchange played out. The Chinese must have owned up when they realized how far their pit bulls’ juvenile scare had gone. Egg on their face, it’s true, but they hardly would want to actually blow up either India or Pakistan. Unfortunately, even a warning issued well in advance would have trouble trickling down through all the communication breakdowns. Who knows what Pakistani general, blinded by the fog of war, triggered that one errant bomb?

“Of course the missile partially malfunctioned—I’m still trying to verify what happened and how. But could the Indians believe it inadvertent, even if the Pakistanis themselves sent an apology before it came down? There was good proof it was an accident: instead of the multiple warheads trained on Mumbai, Islamabad had made only a single launch. The Indians retaliated, as they must—they bombarded Karachi with four to Pakistan’s one. Not just to ensure against malfunction, but to warn against further escalation, to punish for the insult.

“You might think me cold-blooded, but this is one of the best possible outcomes in terms of human cost. Only one or two cities struck, that too almost empty—can you imagine the minuscule probability? There was bound to be an exchange, either now or in the future—things had gone too far. Every war-game simulation I’ve ever seen predicted results more final, more unthinkable, than how this seems to have played out.”

SARITA TALKS A LOT about Karun’s triangle—the trinity the three of us formed, the one the baby will restore. In fact, she gets a bit obsessed with the idea, seeing triads everywhere she goes: sea, land, air; earth, sun, moon; even India, Pakistan, and China. It’s as if she can only deal with the universe now by breaking it down into these triangular building components. “We’re going to have a son,” she announces so often that she might be trying to browbeat her belly into this outcome. The choice of “we” instead of “I,” so alarming to the Jazter sensibility of yore, now gives him a feeling of reassurance. Sarita even claims to have the perfect name: “Karun”—a prospect that completely weirds me out. Too Freudian, I finally get across, and she reluctantly agrees to think of another.

A jag appears in our triangle. Now that life returns to normal, isn’t it time to enrich it once more with the venerable custom of shikar? The Jazter finds Rohil on the dunes of Nagoa Beach one afternoon. Rohil of the long hair, Rohil of the green eyes, Rohil of the olive ancestry that shows in his skin. He’s very young, only twenty or so—but oh, such a promising student.

We start meeting every afternoon in one of the crumbling barracks of the fort. There are no tourists these days, so the guards have gone, the gates never close. The Jazter teaches his eager disciple everything he knows. We mostly just lie in each other’s arms—it’s not really shikar, those days have grown too old. Afterwards, perhaps as a substitute, we play hide-and-seek (though sometimes soldier and sergeant) through the nooks and crannies of the fort.

Perhaps the experience with Karun has sharpened her instincts, because all of a sudden, Sarita knows. “About your friend,” she says one night as I arrange the apron over her. I begin to ask whom she means, but she simply breathes in deeply. “Whoever it is, I just want to tell you it’s OK. I’ve been through this before, and I’m not going to make the same mistake again. I know you have your needs—it’s actually good for us all if someone ties you to this place.” Her forehead creases, but neither anger nor jealousy colors her face.

“Ordinarily, I wouldn’t impose. But these times are hardly normal. The baby’s chances will be so much better with two parents behind him instead of one. If you ever think of leaving, you have to let me know. With Sequeira expecting so much from us, we’ll have to think of what to say.”

I try to assure her of my intention to stay, but can’t quite clear the worry from her eyes. She lies there like a doll with her arms tucked close to her sides under the apron. “I know I might not have much you want. I only have the baby to give.”

The night is much cooler than any so far, and Sarita soon relaxes into slumber beside me. But I cannot sleep. I toss and turn. I stare at the ceiling. Perhaps doing so intently enough will allow my gaze to penetrate through to the sky beyond.

At dawn, I finally get up. I’ll go to the water, I think. The haze swirls around in the incipient light, lifting like mist from the sea. Although a few pieces of wreckage still bob against the dock, by now the tides have swept the bay clean. I look for Afsan’s boat with its mismatched sails and newly fitted mast, before remembering he left last week. I told him he was lucky to have such an adventure ahead. A pioneer embarking into the unknown, like Vasco da Gama, like one of the original Portuguese. “Why don’t you come along?” he replied, glancing at me slyly.

I make my way east, to the jetty below the fort. Steps lead down on either side of the strip, a lone cannon rolls on its side at the end. Across the water floats the old prison island, the sun bubbles on my right under the sea.

I think of Afsan in his boat. Waiting to see the same sunrise. What if I’d taken him up on his offer? What would I have found, how far would I have reached? Sailing along the coast with him, the explorer within me set free?

But there are discoveries waiting here as well. The future is just as uncharted, as unrevealed. The step I have committed to, the role I’ll assume—becoming a father, taking on responsibility. Isn’t it precisely the newness of this experience that attracted me?—the rung towards adulthood, towards filling the gap I sense inside? Had Karun recognized this need, tried to communicate it to me from the beginning? Could he have seen into the future as Sarita claimed, set up this opening as a gift to me?

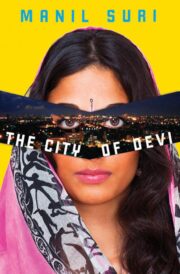

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.