Leaving Sarita proves harder than I think. She cuts off her pleas, stops talking to me. I expect her to enlist Sequeira to exert pressure on me, but she keeps scrupulously mum about her pregnancy. At night, she lies on her back and stares at the ceiling—sometimes, I notice her gently rub her belly. I rush to assist when she falls between the tables one afternoon, but she picks herself up, refusing my hand expressionlessly. Her silence makes me feel so guilty that I start spending my days away, stealing away from the house before she awakes.

Early one morning, I head down to the waterfront to check on Afsan’s progress with his ferry. I’m surprised to see a small crowd already gathered at the beach along the way, pointing out at sea. An enormous rectangular box-like object tosses in the waves—some cry out it’s a truck, others a shipping container. The edges rise high above the water, then crash back with great bursts of spray. For a while I think it will just lurch off, perhaps to heave up on another shore somewhere. But then, as if tired of playing with this toy, the waves lift it one final time and send it hurtling shoreward.

It comes to rest on the beach—a compartment from an electric train, as can be seen from the pantographs still attached to the roof. My heart lurches when I see the “Western Railway” logo on the peeling brown and yellow paint—indisputable evidence that it’s from Bombay’s suburban rails. For a while, I peer through the broken windows, at the metal floors and empty seats. I feel vaguely dissatisfied, as if a bottle has been delivered, but without the requisite message inside. Then I realize the message is the car itself, telling me I will not be returning, the city has not escaped. Curiously, the paint hasn’t scorched so much, so perhaps there’s hope that Mumbai has fared better than Karachi.

I walk along the water for much of the morning, thinking of Karun, seeing our story play out against the Mumbai vistas again. Then I go home and tell Sarita I will stay.

IN SHORT ORDER, the Jazter molts his curmudgeonly crust and gets more intrigued by the coming baby. Perhaps not as excited as Sequeira, who goes around touting it as the miracle child, the new seed for Hindu-Muslim unity, a symbol of religious tolerance to set us free. He somehow manages to procure all sorts of fruit—bananas and guavas and yes, even her obsessively coveted pomegranates, which I peel and de-seed and sometimes juice for Sarita. Her teeth turn crimson, her eyes tear a little each time.

On nights when the dusty haze rolls in to fill the air, I cover Sarita with a dentist’s X-ray apron Sequeira has found, to protect the unborn baby from any lurking radiation. She lies under it, sweating in the dark, and I fan her with an old newspaper to cool her off. Sometimes, she gets so warm that I have to sponge her forehead with a wet towel. It’s probably overkill, we both realize—we simply don’t want to take a chance. The heat is good, I tell her—she’ll hatch her egg more quickly, like a chicken. She must be developing a sense of humor (Allah be praised), because she laughs.

For the first time, I get a sense of her physical self. The sense that eluded me when I lay next to her on our “suhaag raat” at Sequeira’s club (even sniffed her, as I embarrassedly recall). I feel the familiarity in her touch as she holds on to me for support, the intimacy in her gaze as she waits for me to lay the apron over her. Her expression expectant, her body compliant, like someone being packed in sand at the beach for a play burial.

Sometimes, while she sits up to read in bed, I can glimpse what Karun might have seen in her. Her brow smooth as she gazes at the page, her skin lustrous in the window light. The curve of her neck leading like a fluid brushstroke to the roundness of her breast, the rise in her belly. A certain shy voluptuousness she may not even be aware of, which I can envision Karun may have found appealing. Of course, in the rosy bloom of her pregnancy these days, she simply radiates beauty. The Jazter blushes at his former ungenerous assessments—made, he sheepishly admits, in the heat of jealousy.

Every so often I imagine hugging Sarita as we lie together at night. Not in a sexual way or as an erotic experiment, but just because I think her softness would feel nice. I remain on my carefully separated mat, however—I suspect it would confuse her otherwise. As it is, Sequeira hints that given the country’s probable need for repopulating, we should already start thinking of having more children (an entire litter of mixed-breed pups, why not?). I stay on the lookout for opportunities to convey my lack of romantic intentions to Sarita. Fortunately, the Hindus have endless brother-sister festivals like Rakhi, perhaps to express precisely such sentiments.

Tonight, I squeeze her hand and pat the apron over her belly. She’s been pining not only for Karun, but also her parents and sister and infant nephew in the south somewhere. I reassure her they should be fine, that she will see them soon enough one day. Perhaps it’s the surging hormones, but she keeps latching onto thoughts that bring her down. “All that haze outside. Won’t it reduce our life spans?”

“Perhaps. But it’s a lot better than being dead. Besides, if everyone’s going to live a month or two shorter, what of it? Aren’t statisticians supposed to look at the average?”

On the contrary, she informs me somewhat severely, it’s the standard deviation that’s needed, to figure out what percentage might get shortchanged at the left end of the curve. “If, that is, the distribution is Gaussian,” she adds in warning, as if I’m raring to go out and commit a statistical crime.

I tell her it doesn’t matter. “We’re six hundred kilometers away from Karachi, three hundred from Mumbai. Where we still don’t know what happened, incidentally. If anything, you’ll be at the favorable end of the curve, with all the care Sequeira’s expending.”

This also makes her morose. “All the fruit he brings, this shelter, this safety. When so many are dead—I feel so guilty.”

I point out that the only alternative to survivor’s guilt is eternal serenity: the clear and happy-go-lucky conscience of a corpse. “Besides, why don’t you think instead of all the people saved? Lahore to Calcutta, Chennai to Rawalpindi—Vincent’s determined that every single one of the remaining cities came through all right. Remember, by then even Mumbai and Karachi had almost emptied. The Pakistanis got a warning too, just like we did—think of the ninety percent or more who fled in that fortnight.”

I do a quick calculation for her: the loss cannot be more than 0.4 percent of the combined population of the two countries, 0.08 percent of the world count. “It might sound callous, but one has to think of percentages at a time like this.”

She stares at my numbers. “It’s actually 0.3 and 0.06 percent. You made an arithmetic mistake.” She starts to show me all the people she’s saved, then puts the paper down. We both know there’s no way around the sickening magnitudes still represented by these decimals; the horror of all those burnt and twisted bodies cannot be juggled away.

ON HAZE-FREE NIGHTS when Sarita doesn’t need my ministrations, I descend to Vincent’s candlelit communications center in the basement. He has cannibalized the hand-cranked radio, along with various other pieces of equipment (some “borrowed” from the Diu airport) to construct a transceiver set. “Almost as good as the ham radio I had, before the power surges blew it out.” Wires leading outside can be connected to different antenna configurations laid out in the garden (his “aerial farm,” he calls it)—for nighttime hours, he finds the swastika shape works best. The family has dedicated the diesel generator, with its precious remaining supply of fuel, to his communications experiments.

With his enhanced setup, Vincent manages to put together a much clearer picture of what lies beyond Diu’s shores. The two-way communication allows him to quiz operators to test their genuineness. “What numbers do you see on the large sign at the end of the runway?” he grills someone claiming to be at Delhi airport, and they promptly go off the air. “From where did you say you viewed the bomb fall on Hyderabad, old man?” he asks VU2ARF, who confesses he only heard it thirdhand.

He succeeds in contacting not one, but two hams in Lahore, and they both talk about recently returning from the countryside. “Not just here and Rawalpindi, but also the other cities. People are still trickling back, after fleeing the Indian nuclear threat.” The modus operandi of the warnings sounds exactly the same—swamping of the internet, followed by a deluge of calls on mobiles. “But what your savages did to Karachi—who imagined anyone would actually go through with it?”

Mumbai remains resistant to revealing its fate. Vincent still hasn’t been able to find anyone transmitting while physically in the city. The most persistent rumors claim a warhead was indeed launched by the Pakistanis, but hampered by some sort of malfunction—the device detonated either too high in the atmosphere, or several kilometers off course. If so, the most severe destruction may have occurred within a smaller radius, the fallout leaving Mumbai virtually uncontaminated. Some of the airwave chatter sounds clearly wishful: the Devi has saved her city, the missile has fallen harmlessly into the sea, the Hindus have reconciled with the Muslims, even the cracks along the shoreline have begun to heal. More apocalyptic assertions, of shockwaves liquefying reclaimed land to plunge large sections of the city into the sea, appear just as spurious. Nobody can provide a plausible explanation as to why India and Pakistan each stopped at exactly one target instead of throwing their all into the melee.

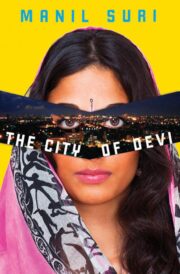

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.