This is the still I will carry with me, the image by which I will remember him. His eyes glistening with gratefulness, his smile joyfully lit, as if he can’t believe his luck, the fortune he’s hit. The unsureness that’s always lingered like an underlying shadow replaced by the new radiance of belonging on his face.

The sea spreads out as carefree as before, smoke from the smoldering deck tinges the spray. We rise and fall under the empty sky, borne back towards the land by the frisking waves.

JAZ

18

WHO KNEW THE JAZTER WOULD BE CONDEMNED TO COMPOSE THESE thoughts? That his story would be led so astray? This, then, is the harsh lesson he must learn. Endings need to be lived, they cannot be ordained.

Afsan manages to steer us into Arnala, a small port just north of Bombay. While Sequeira uses his mafia connections to wrangle another boat, Sarita and I search the brush above the shore for wood. Some of the pieces are too green, others too thick—many of the branches are little more than twigs. I try not to think of what they’re for, try to focus on the task at hand through my shock.

We set up the pyre on the beach itself, well above the tide line. Sarita says she will light it alone, but relents at the last minute, inviting me to assist. Together, we hold a burning branch to the stack on which Karun reposes—it seems to take forever to catch. As the flames leap up, singeing the body I’ve cradled and caressed and loved, I have to hold on to Sarita to be able to watch. She clutches me as well. Neither of us wants to leave before the embers cool, but Sequeira eases us away. He arranges for one of the fishermen to sort through the ashes in our absence and immerse the remains.

Back at sea, my grief gives way to rage. Rage against the enemy, rage against the war, rage against everything that’s conspired to snatch Karun away. How arbitrary, how wasteful and unfair, after the impossible gauntlet of hurdles we overcame. I scour the sky like King Kong, ready to reach up and pluck off Pakistani planes. Bring on your worst, I silently rail—bullets, bombs, nuclear explosions—I’m ready to confront them all.

But the horizon remains untroubled by jets or mushroom clouds. The sky doesn’t rend, no seaquake announced the arrival of the scheduled doomsday. We journey through the night, reaching Diu on the nineteenth around eleven a.m.

The town is in a panic, even though Ahmedabad, the nearest target on the list of eight, lies three hundred kilometers north. People crowd the dock waiting for long-departed boats to convey them to safe havens (where these might be located, nobody can probably pinpoint). Some hunker down in their houses, hoping their bolted doors and shuttered windows will persuade any impending malignancy to move on; others roam the streets with clubs and pellet guns and old muskets, searching, perhaps, for the leader seasoned enough to mobilize them. “Why did you leave Mumbai?” an acquaintance asks upon spotting Sequeira. “Hasn’t the Devi appeared there in person to keep away the bomb?”

Sequeira takes us to his family mansion off Fort Road, where his siblings Vincent, Paul, and Mildred live in a large joint household. He tells them about our recent bereavement, but enthralled by the approaching cataclysm, they barely register our grief. Vincent and his son take turns cranking a hand-generated emergency radio, only to get static no matter where they set the dial. Sarita and I crowd around as well—perhaps the future will distract us from our own mourning. But our attention quickly veers back—nothing can feel as real or compelling as Karun’s loss. The drama of Diu’s survival (or for that matter our own) is like a television show in comparison, one we find only moderately engaging.

The sun emerges as brightly the next morning. The heavens look clean and radiant. Relief washes through the streets and the docks, now that the nineteenth has passed, now that Diu has survived the date without any harm, any nuclear shockwaves. Sequeira’s sister Mildred complains of a smokiness in her throat, a greenish tinge to the air. But by the time the magnificent sunset lights up the seafront, with its golden rays reaching towards the old Portuguese church on the hill like the fingers of God, she agrees it has to be her imagination. The next evening, when the sun makes an even more spectacular exit, with eloquent streaks of orange and red and magenta, she’s ready to proclaim the end of the war. The local Jain community floats little earthenware oil lamps into the sea to give thanks—a ritual that soon encompasses Hindus and Muslims and Christians as well.

Sequeira drags us to the celebration by the water’s edge to cheer us up. I watch as people launch bits of candles on rafts, diyas made of wicks and tin cans. All I can think of, as the points of twinkling gratefulness carpet the bay, is Karun. Could we have remained safe in Bombay, did we lose him for naught? What if he’d survived just one more day?—would that have conducted him past the end of the war?

Mildred interrupts my rumination to tell me about Diu’s charmed existence. Except for a stray air raid on some old office buildings in the center, the town has remained unscathed. Moreover, religious rancor has not been a problem—not like nearby Veraval, with its brutal massacres of Muslims. “Yes, our electricity’s gone, and our lifeblood of trade choked off—we can no longer find flour in the market, and half our workers have wandered away. But show me one place in the world that doesn’t have these problems now. Diu’s escaped the worst of it, thanks to the lord.”

More people turn out the next evening, drawn by the sunset, which now scintillates with an extended palette from yellow to purple. Even I’m amazed by the unusual striations of green, ribbing the sky like a sprawling celestial skeleton. Revelers throng the terraces of the old houses overlooking the harbor to watch the show below, the diya lamps now replaced by triumphant bonfires blazing from victory floats. Something about this escalating drama makes me uneasy. We have yet to receive any news from the outside, even from Ahmedabad (Vincent can still only crank static from his radio). I try to recall what I’ve read about particulates in the atmosphere, about dazzling sunsets after volcano eruptions. But caught up in the town’s festive mood, I decide I’m fretting for no good reason.

The fish start washing up at dawn. By midmorning, the shore is so thick with them that the water no longer flows in waves, sloshing instead against a solid rim of carcasses. Although most of the fish have decomposed or been partially eaten, several still have intact heads, their eyes clear and wide open, as if witness to a sight so shocking it has caused instant death. Given the scarcity of food supplies, some of the townsfolk go up with baskets to salvage the more edible-looking chunks.

The sea soon turns black, putting an end to the foraging. At first, it looks like a vast expanse of shadow, the kind that rolls in under approaching clouds. But the sky is clear, and the shadow turns out to have great density and substance—clumps of ash and filament and debris, as if a giant cremation urn has been emptied into the sea. Larger pieces float in as the tide intensifies—charred lumber and furniture, blackened corpses that joust with the fish for space on the beach, even an enormous banyan, its leafless branches as tarry as its roots, hurled onto shore by the increasingly angry waves. At some point, it starts looking like a tsunami, and residents gather at the fort, abandoning their low-lying houses. But although the sea advances all the way past the waterfront stalls and across Fort Road, it eventually subsides, leaving behind a profusion of listlessly floating objects. A mass one could almost walk across, like ice floes in an Arctic waterway.

Is the debris radioactive? The local government surveyor examines the depth of the char marks and declares it likely. Parents start shrieking at children to get away from the banyan, whose roots have somehow become irresistible playthings to swing from. A woman hysterically tries to vomit up the fish she’s ingested for lunch. A gang of urchins continues sorting through the wreckage for valuables, unmindful of the commotion.

Assuming the soundness of the surveyor’s diagnosis, a city has been hit. The question is which one? The only possibility can be Bombay—none of the other seven places on the list lie on the Arabian Sea. Except it’s October, when the monsoon currents are in the process of reversing. The debris could equally well have floated in from the other direction, down from Pakistan—in which case the city destroyed would be Karachi. Or even some place further, like Muscat, in Oman.

The panic, which bubbled off into euphoria just a few mornings ago, surges back. Nuclear bombs are like potato chips, nobody can stop at just one. Every scenario predicts that a country under attack will launch all its weapons at once to avoid losing them. Does this mean all eight targets on the list have been struck? What about the remaining two hundred or so warheads in the combined possession of India and Pakistan? With even a single missile fired, wouldn’t the two enemies have responded by launching this entire arsenal?

Continuing this line of thought, once such attacks started, wouldn’t other countries be unavoidably drawn in? Could they have set off enough devices to obliterate life on the entire planet?

The true horror of the bodies in the harbor starts sinking in: this just represents a speck of the hundreds of thousands already killed. How many untold more are set to perish?—does Diu have any chance of escape? All eyes turn to the sky, to keep watch for the legendary death clouds. The toxic masses which must now rove the globe like giant dinosaurs, devouring anything that moves in their path. Depending on how many bombs have detonated, the clouds will either dissipate over time or merge together to wipe us all out. Sure enough, the first smudge appears a day later, clotting the air from sea to sky in a sweater-like knit of grey. As some flee and others shutter themselves, the wind intervenes to blow the mass off to the north. A second cloud the next week blusters right into town. But it brings nothing more baneful than rain—perhaps a holdover from the long-expended monsoon.

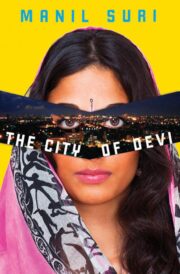

"The City of Devi" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The City of Devi". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The City of Devi" друзьям в соцсетях.