When Mandelstam spoke his voice had taken an edge.

“Who are you with tonight?” He spoke as a brother might, or a father. Someone responsible for her in some way. Or as an ex-lover. Reminding her that without a Union membership, she could not have gained entrance on her own merit. But perhaps more meaningfully, he was demonstrating his right to ask that question in that manner.

An embarrassed smile fluttered across her face; she provided a name. Bulgakov didn’t recognize it, but Mandelstam nodded.

“You look well,” she said. She sounded mildly hopeful in this.

“Perhaps in this lighting I do.”

She continued with less certainty. “And Nadya?”

“She actually is quite well. But I don’t think I’ll tell her you asked.”

He was condescending to the point of contempt, Bulgakov thought. He reached for Mandelstam’s arm. She’d come to them, after all. Was there a need for this? Mandelstam moved his arm away.

“I simply wanted to say ‘hello.’” She said this without apology or defense, as if a little tired.

“And so you have,” he said flatly.

“I mean there’s no reason for us to pretend we don’t know each other,” she said. She seemed not to lose courage, but hope.

Mandelstam frowned at the cloth and swept its crumbs aside as though he no longer had patience for them. They bounced lightly off the skirt of her gown.

“You are far too willing to overlook my shortcomings, my dear,” he said. He smoothed the now-clean cloth with his hand.

Only her eyes revealed her distress, her unwillingness to believe his animosity and yet her acceptance of it. Her vulnerability was breathtaking. He wondered if Mandelstam saw this as well.

“Perhaps,” she said quickly. “That would be my shortcoming.” She turned to Bulgakov. “Please enjoy your meal,” she said.

“We’ve finished,” said Bulgakov, correcting her. “It wasn’t particularly good.”

“Ah, well then, enjoy—” She left her sentiment unfinished, unable to come up with a better idea of what they were to delight in. She’d already turned. He watched her recede, feeling as though he’d allowed her to escape.

Mandelstam watched her as well, his expression very different from the one just moments before. There was an old affection, perhaps one that had been retired, yet nonetheless remembered, and it occurred to Bulgakov that she was the reason they’d dined here this evening. She disappeared through one of the veranda doors and Mandelstam’s gaze found his. “She should know better,” Mandelstam said.

“I think she does now.”

“I suspect not.”

The door’s opening maintained its velvety darkness. Bulgakov looked for her to reappear but it remained empty.

“We were speaking of your play,” Mandelstam said.

Bulgakov thought that perhaps he’d rather talk about Margarita.

Mandelstam and Bulgakov left the restaurant together. The streets were wet and empty; the sky was low. Bulgakov felt the hum of alcohol out to his fingertips. He felt connected to the dense warm air that rose from the glistening asphalt. He wondered where Margarita might be at that moment. He imagined her alone, perhaps on a street like this one, then remembered she was with someone else. Was she holding his hand; his arm? Had he provided her comfort? He wondered how he might see her again.

Two uniformed men stepped into the street. Mandelstam stopped then immediately moved away from Bulgakov, and the four men stood apart, the points of some ill-formed square. Bulgakov was for a moment confused.

The gold threads of the police insignia glimmered in the light of a nearby streetlamp.

“Citizens. May we see your documents?” said the taller man.

Mandelstam provided a cache of papers. Bulgakov extended his as well and they were snatched up by the shorter of the two. This one mouthed the words as he silently read them.

“The poet Mandelstam,” said the taller policeman. He sounded genuinely pleased.

“You never know who you might find roaming the streets at night,” said the poet.

The other officer continued to review Bulgakov’s papers as if disappointed he’d not caught a larger fish. “Are you together?” he asked finally. He handed the papers back.

“No,” said Mandelstam. He seemed about to add something further then stopped. The taller officer studied Bulgakov with growing interest.

Bulgakov laughed. “You are Mandelstam?” he said. “I thought he was a much younger man.” He swayed suddenly and stepped back to regain his balance. The shorter officer shined a flashlight in his face and the world disappeared in its glare. He heard, “Stand to, Citizen.” The light moved and the street reappeared, muddled with spots. The shorter officer stepped closer. To Bulgakov it seemed this one was a clown’s version of a policeman. He laughed aloud at the thought.

The shorter officer was about to speak but the other interrupted. “Comrade Poet, you give us a poem. We’d like that.”

Mandelstam shook his head. “I can’t think of one, friends. Perhaps another time.”

The taller officer didn’t move. It was clear he was unsatisfied with that answer.

“I know a poem,” said Bulgakov. “One you will like. ‘There once was a whore from Kiev.’” He paused. “No, Novgorod. Yes. ‘There once was a whore from Novgorod.’”

The officers stiffened. Bulgakov noticed this in his blur but went on.

“No, it can’t be Novgorod. The rhythm’s all wrong. I can see you gentlemen are not enthusiasts of great literature.”

Mandelstam spoke. “Enough.”

“You’re not so terribly funny,” chimed the shorter officer. “Perhaps you would like to be arrested for public drunkenness.” He hooked his thumbs onto his belt.

“Oh but I am funny,” said Bulgakov in a show of astonishment. “I am a satirist. Humor is my tool.” He lowered his voice as if conspiratorial. “It is my weapon.”

The policeman looked alarmed.

“But perhaps you think satire is a kind of fish that swims in the Volga.”

“Enough.” This time it seemed Mandelstam was speaking to the greater world. “I will give you a poem.” He touched Bulgakov’s sleeve.

The poet’s manner had a dousing effect and Bulgakov was given to the uncomfortable sense that this was something Mandelstam had intended; and even if it was not precisely intended, then perhaps it was quite simply an opportunity he would take.

The streets were empty, as if Moscow had availed them some privacy. Mandelstam’s voice rose as though he was speaking to a gathering of hundreds, as though this was his most beloved of works.

Mandelstam said:

We live, deaf to the land beneath us,

Ten steps away no one hears our speeches,

All we hear is the Kremlin mountaineer,

The murderer and peasant-slayer.

His fingers are fat as grubs

And the words, final as lead weights, fall from his lips,

His cockroach whiskers leer

And his boots gleam.

Every killing is a treat

For the broad-chested Ossete.

It was the shorter officer who made a sound, a sharp sigh.

Mandelstam licked his lips, as though he’d become parched. “I think even a Bolshevik can understand that much,” he said.

With that Bulgakov staggered forward and threw his arms around Mandelstam’s shoulders. He pressed the poet’s head into his neck.

“He’s drunk, Comrades. Can’t you see? What a night we’ve had! His words—what words—I could barely understand such slurring. Can’t you see—his wife left him, truly—just today. Left him for a younger man, a bookkeeper. The poor old goat. And his daughter is pregnant.” This he added in a whisper.

“Stand away,” said the taller policeman. The baton was in his hand.

It seemed ridiculous—could this be happening? He clutched Mandelstam harder. “No, no, no—he’s drunk, I tell you. I’ll take him home. I’ll tuck him in. The headache he’ll have tomorrow. I should drive a car over his foot so he can forget the pain in his head.” He looked from one officer to the other. He maneuvered Mandelstam past.

He broke into a jog, half-dragging the poet down the street. He imagined them following. They weren’t far from the DRAMALIT house where Mandelstam shared an apartment with his wife.

He thrust them both through the front door. The street behind was silent. Only then did he release him.

“You should come by tomorrow,” said Mandelstam. “There may be an apartment made newly available. A nice place, I hear.” He appeared to enjoy his joke.

Bulgakov was shaking. “I don’t think they followed us,” he said.

Mandelstam shook his head. He seemed suddenly quite weary. “They’re upstairs.” He glanced at the ceiling. “Can you hear them? Roaches in the walls.”

“Here? They cannot be here already.”

The poet stepped back into the hall under the ceiling light. His scalp shone brightly. He looked upward. “She’s alone with them,” he said. He meant his wife. “They will have a time of it.” He sounded mildly sympathetic.

“We must get you away. We’ll go to my place. It’s not far.”

There was a distant thump, then the thinner crack of breaking wood. Mandelstam closed his eyes. “The sideboard. What we went through to haul that monstrosity up those stairs.”

Bulgakov reached for the poet’s arm. Tentatively, as if in this gesture he might disappear. “What can I do?” he said.

Mandelstam looked at him as though he’d not considered this before and Bulgakov saw in his face his sad realization: there was nothing Bulgakov could do; there was nothing anyone could do.

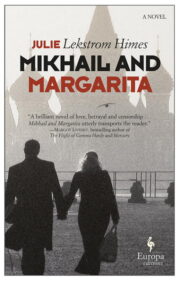

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.