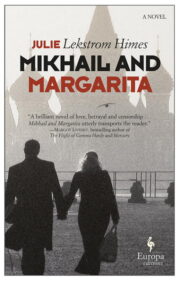

Julie Lekstrom Himes

MIKHAIL AND MARGARITA

For Len and Barbara

PART I

ENTER THE HERO

CHAPTER 1

History came late to Russia. Geography isolated her and isolation defined her. In the ninth century, pagan Vikings discovered her from the north; Muslim Khazars ruled her from the south. The Cyrillic alphabet, which was to craft her story, made its way across the Carpathian Mountains on the backs of Macedonian monks only in the winding years of the tenth century. Even nine centuries later, Pushkin and Tolstoy were yet inventing those words which in Russian did not exist: gesture and sympathy, impulse and imagination, individuality.

It would be the task of her subsequent writers to try to define them.

Mikhail Afanasievich Bulgakov sat with his back to an open window in the richly appointed restaurant of Moscow’s All-Soviets Writers Union. It was late spring of 1933. His friend Osip Mandelstam leaned across their small table to emphasize a point, but Bulgakov wasn’t listening. He was thinking instead of his friend’s young lover, imagining how he might steal her from him.

The day preceding had been blisteringly hot. By midday the waitstaff had tied back the heavy damask curtains and pushed open the high, triple casing windows that encircled the polygonal room. A series of French doors opened onto a wide verandah that was likewise arranged with tables and chairs for dining. Repeatedly, the restaurant manager stood in the dining room, then on the painted planking of the verandah, then back again, considering the temperature and ventilation of each space. Finally, by late afternoon, he set the staff to move half a dozen additional tables from inside, through the open doors, and onto the already crowded verandah. He went from table to table with his meter-stick, measuring and ordering adjustments and measuring again. Shortly before dusk, dense green-grey clouds filled the sky and opened themselves upon the streets of Moscow. The heavy drapes floated up in the wind and slapped down against the window moldings. Enormous raindrops like errant birds flew through the open windows and between the broad porch columns, spotting the tablecloths and napkins and puddling on the polished wood floor. The sun returned only to dip below the darkening outlines of buildings, steam rose from the sizzled streets, and frantic waitstaff hustled about, blotting and wiping and mopping. By the time the restaurant opened at ten that night everything that needed to be dried or replaced had been considered, save one—not a single grain of salt could be coaxed from its shaker. After the second request for fresh salt, it was clear there was no more to be found either in the back storage closets or in the basement, and the manager sent one of the younger dishwashers out to procure some from a nearby restaurant with an extra ten-ruble note to pay for the speed of a cab. Not a block from the restaurant the dishwasher discharged the driver with a few kopeks and pocketed the rest. When the first did not return, the manager sent a second dishwasher on the same errand, only now, two washers short, dirty plates and glasses began to accumulate and service noticeably slowed. With the continuing requests, he set two of the waitstaff to dump several shakers’ worth into a pestle and grind the grains apart, but the clumps reformed almost immediately. Meanwhile, the manager went from table to table apologizing and offering assurance they were only minutes from acquiring new salt that would be swiftly and equitably distributed. In any case, he told them, he hoped their meals were prepared to their satisfaction.

The manager paused from his rounds and stood in the doorway between the dining room and the verandah, scanning the guests. He recognized Mandelstam; otherwise there was no one of terrific consequence; the night could not be counted an utter disaster.

The air outside smelled of ozone, and, slightly cooled by the evening rain, it floated through the window behind Bulgakov. The squat alcohol lamps on each table were protected by small translucent shades and did not flicker. Other patrons, sweating in the dim light, moved little. The edges of conversations were muted as well. Several tables away, a young woman in a crumpled orange dress fed caviar to an older man with a poorly dyed goatee. To their right, another man, a minor poet, argued with his two companions, jabbing his finger into his palm, yet even this seemed vague and lacking conviction. Near the doors to the verandah, a band played a low and drifting melody.

Mandelstam sat back as though he’d made his point. The light from the lamp bloomed between them. Mandelstam’s thinning dark hair ringed his scalp in an untidy damp fringe. His face was pale and moist in the heat. He was forty-two, only a year older than Bulgakov, yet he seemed more aged as if he’d lived in a different time or under more difficult circumstances. How he’d been able to attract the much younger Margarita Nikoveyena had occupied Bulgakov’s thoughts on not a few occasions before this evening.

Bulgakov glanced over the room. Beyond the doors leading to the veranda there was the turn of a pale gown; a flicker of bare shoulders. A slender neck, then gone. Could she be here this evening? “Who the devil is that?” he murmured.

“You’re not listening,” said Mandelstam. It seemed more a weary reflection than an accusation. He maintained what Bulgakov would consider a too-generous gaze.

“That’s true.” Bulgakov smiled a little with this admission. He felt some guilt about this. They met infrequently these days. Their friendship had evolved from a mentorship of sorts, begun over a decade earlier when Bulgakov had moved to Moscow and started writing. Years later and now with some success of his own, their friendship had dwindled rather than strengthened. Bulgakov blamed himself generally. Their dinner tonight had been Mandelstam’s suggestion. Bulgakov could not remember another meeting that had come at the poet’s request. Even so, he had almost declined at the last moment, for no better reasons than the poor weather and the mediocre meal which was to be expected midweek at the Writers’ Union. As he’d come across the room, unreasonably late and with an excuse forming, Mandelstam’s gaunt face was so at odds with the room’s richness that his first words were not a request for pardon but a pointed inquiry into the state of his health. Mandelstam assured him that he was fine, and yet it was the pleasure he showed at Bulgakov’s arrival, and his willingness to set aside the annoyance he must have felt for being made to wait, which caused Bulgakov to consider that there was something Mandelstam required from him. This was the first time Bulgakov had ever thought such a thing.

Mandelstam’s interest turned to Bulgakov’s well-being.

“Why don’t you get away? Go to Peredelkino—it’s quite nice this time of year,” said Mandelstam.

Six dachas—parceled out amongst three thousand writers. The privilege of Union membership for the politically connected. Bulgakov pretended this was a serious suggestion. “I’ve not had a turn.”

“I’ve been a number of times.” Bulgakov’s reluctance to engage in Union politics was an old conversation. “It’s not impossible. Who do you go to?”

Bulgakov laughed. “Who would have me?” His self-deprecation was false, but he had no desire for patronage. He preferred to remain in some way invisible. Not his work, of course, but for himself, this was fine; perhaps even best.

Mandelstam shook his head. “Everyone goes to someone. You don’t have to live in that place of yours. You could do better. Committee members, they love writers—makes them feel cultured. I could introduce you.”

Bulgakov glanced away again. “Is that Likovoyev? I haven’t seen him in months.”

“He’s been at Peredelkino.”

Of course. Bulgakov smiled. “And I thought he’d died.”

Mandelstam lowered his head, whether from the heat or the conversation, it was difficult to say. He seemed disinclined to pursue other old topics: the necessity of placating critics, of transforming editors and directors and producers into advocates. Bulgakov was grateful, though he considered that in this, and possibly in other ways, too, he’d plumbed the limits of a friend’s fortitude.

“Perhaps you should write poetry,” said Mandelstam.

“Aren’t you concerned I’d give you competition?” Bulgakov had intended this to be funny. He downed what remained of his vodka.

Mandelstam waited for his attention. “Only in this country is poetry respected,” he said. “There’s no place where more people are killed for it.”

He was prone to speak in such a manner. Bulgakov found it tiresome; he did not share his friend’s political discontent. This was not so much a stance, he told himself, as a lack of interest. He barely read the papers; he listened to the radio for its music. Yet because of this edge in Mandelstam a certain wariness was necessary, a constant recalibration of the space of their relationship. That was what was tiresome. He noticed that the poet had acquired a spot on his shirt since the start of their dinner. He was often careless, and Bulgakov found himself further annoyed by this. “One might argue, then, that writing poetry would not be such a good idea.”

Mandelstam smiled. Perhaps this was so, he agreed.

Likovoyev moved from table to table, clasping hands as each patron rose from his seat. Only brief exchanges, and Bulgakov observed with mild interest as shifts in the Union’s hierarchy were revealed. Likovoyev went next to the Art Theater’s new librettist; then bent low to ingratiate himself with the man’s young wife, a former countess, holding her hand for too long, ignoring her husband until she looked away, embarrassed. He was stork-like in his maneuverings; his awkwardness made him even more comedic. Bulgakov’s lips parted.

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.