“What is it?” said Mandelstam.

“Our beloved critic,” said Bulgakov. “Among his many crimes, he is an appalling flirt.”

“My wife seems to be immune to his advances.”

“You are fortunate.”

“In some ways, Nadya is like a nun. How is your Tatiana?”

The waiter appeared and replaced his drink. Bulgakov waited until he’d receded. “She’s moved in with her sister and her husband.”

Mandelstam seemed to check his surprise. It occurred to Bulgakov that this was already common knowledge. Their wives had been friends of a sort, sharing the burden of writer-husbands.

“Their apartment is larger,” said Bulgakov. “And—they have a private bath.”

Mandelstam nodded in feigned support of the wife. “I would leave you, too.”

Likovoyev moved on from the librettist and was embracing a young poet. Bulgakov emptied his glass again. He remembered the precise moment he had fallen out of love with his wife. An acquaintance had introduced them at Bulgakov’s request. For weeks she’d gently rebuffed his advances with teasing words he’d found endearing, then one evening, without explanation, she’d stayed. He remembered her sitting on the edge of his bed, the pearl-shaped buttons of her blouse between her fingers, undressing for him; he remembered the low angle of orange sunlight through the dirty window. He remembered watching his desire fall away as the chemise dropped from her shoulders. If only she would leave, he thought. Perhaps if she had, his desire would have returned; but she’d remained.

He’d married her anyway. He felt their lovemaking had been a kind of agreement to this. And he felt sorry for her, for being unloved. And she was fine, really. They got along well. She left him alone to write and was sufficiently distracting when the loneliness turned on him.

Likovoyev was standing by their table. Startled, Bulgakov laughed aloud. “I thought you were the waiter,” said Bulgakov, lifting his empty glass.

Likovoyev bared his teeth in what might be called a smile.

Mandelstam interceded. “You look remarkable. Your time at Peredelkino served you well.”

“It did,” said the critic. “I banished all thoughts of this place, I must say, all—except—inexplicably, you.” He nodded to Bulgakov.

“Then you must return, immediately, and try again,” said Bulgakov. “I will petition the Union Chairman on your behalf, first thing tomorrow.”

Likovoyev ignored this. “I understand you have a new play under production at the MAT. All is going smoothly, I pray?”

“We open at the end of the month.” Bulgakov didn’t bother to restrain a bit of swagger.

“So glad to hear. I’d heard mention of a delay.” Likovoyev hesitated as though he might say more, then changed his mind. “I was obviously misinformed.”

This was unexpected. “No,” said Bulgakov, rather too quickly. “No. Not at all.” Likovoyev looked again at Mandelstam as if for some sort of verification.

Bulgakov wanted to say that the play was progressing well, ahead of schedule, in fact, though this wasn’t true. They were behind, but not irrevocably. Perhaps seven or eight days; certainly no more than two weeks. But the delay wasn’t entirely his concern. The director, Stanislawski, had seemed to be avoiding him of late, locking himself in his office for hours until Bulgakov would bully his assistant to open it, only then to find that the director had somehow slipped away. Bulgakov had convinced himself this was all his imagining but now his worries bloomed afresh. He wanted to question Likovoyev further, but the other was already speaking.

“Frivolous gossip, then, no doubt. I knew it was nothing to heed.”

“Stanislawski has made no mention—” Bulgakov began. Mandelstam frowned.

“Yes? I am so relieved,” said Likovoyev. “And thankful to have spoken with you.” He nodded. “I will look forward to Moliere’s opening—and to my humble review.”

“Yes—to your review,” Bulgakov echoed. Some part of him vaguely wished the critic would stay. For the first time, he looked forward to a Likovoyev review.

“I won’t keep you from your meal.” Likovoyev seemed more jovial than when he’d arrived, as though he’d extracted the better part of their good mood. “Please give my regards to your lovely wives.” He bowed and turned away. Bulgakov watched him recede.

Mandelstam leaned forward. “He’s not the reason for your—for Tatiana’s—”

Bulgakov shook his head. “No, that was my fault.” The critic was already several tables away. He bent low, to address some other writer’s wife. At the woman’s words, he dropped his head to the side, his eyes boring into hers. Bulgakov recognized the harmless gestures. Now he could almost forgive him for them.

He turned to Mandelstam. “What about a delay? Have you heard such rumors? Have you?”

Mandelstam was poking the remains of his dinner with his fork. “You’ve spoken with Stanislawski yourself. All is fine.”

“Yes, we’ve spoken.” Bulgakov tried to remember the last time they had. “I must speak with him again.” He needed this production. Other recent efforts had been poorly received and short-lived.

“I’m surprised he’s not here tonight,” said Mandelstam. He considered a nondescript piece of meat. “Of course, it is a Tuesday.”

Likovoyev kissed the hand of the writer’s wife. Bulgakov watched him straighten and bow to her, then to the husband, helpless beside her. The woman lifted her eyes to the critic in a kind of wonderment; a combination of mild loathing and speculation. Bulgakov looked away.

He’d thought nothing of Likovoyev’s flirtations with his wife. Nothing whatsoever, except some faint gratitude that the critic provided something which Bulgakov lacked all interest in supplying. That Likovoyev’s stilted affectations might satisfy her in some small way. They, he and Tatiana, had laughed about him, yet perhaps, she had laughed not as much. He’d considered her secret satisfaction with the critic’s attentions a kind of naïveté that should not have been surprising. He wasn’t surprised and hadn’t begrudged her those small pleasures.

There was no crime, no clandestine tryst that had come between them. Nothing save the briefest reluctance, the sparest of pauses, one afternoon as he’d stuttered through his regular tirade about him. For the first time she had not immediately agreed. For the first time she’d been quiet. And in that silence he saw her consideration for the critic, her alliance with him, and realized that this Likovoyev, though incapable of comprehending even the most lucid of writing, could nonetheless reveal in his boorish maneuverings a desolation in her far greater than some naïveté. Bulgakov turned to her for some explanation. She pressed her lips together and looked away as if something had passed their window.

Afterwards, he told himself she did not matter so much; it’d been a mistake from the start and it was easier to let her go. She did not leave right away, but drifted further and further, until one day her belongings slipped away as well. He came home that afternoon to those empty spaces. He left them that way for days, hangers in the wardrobe, the place by the door where her shoes had stood. He found reasons not to fill them; he told himself, though, it was not because she might return. It was not because her things might again need a place to stay.

He found his glass and tipped it forward to pool the remaining drops. He lacked the power to maneuver the world in his favor; he could not even will the waiter to sedate him with more drink. He started to lift it but found his hand restrained.

“Talk to Stanislawski,” said Mandelstam. He nodded as if he understood the problem.

Bulgakov considered his glass. “I will,” he said. Osip relaxed his hand and Bulgakov tipped back the last drops.

The musicians had begun to play again; they took up a jazz line. Music filled the spaces between conversations. Mandelstam frowned as if he’d been interrupted. Then he looked upward. Someone was by their table.

“Good evening, my dear,” he said. He sounded slightly annoyed.

The pale gown from before was beside them. It was Margarita Nikoveyeva.

Bulgakov had seen her before, though not with the poet. They’d tried to conceal their affair although many, even Mandelstam’s wife, it was said, knew of it. There had been the time, the previous fall, at a party in this very room. He’d watched as she’d put off the advances of another man. At one point she’d looked about as though for some means of escape, and caught his gaze. Bulgakov had smiled, both sympathetic and duplicitous, and across that space they had shared an understanding. Or so he’d thought.

Tonight she was different, though. Indeed, all of her seemed unreasonably pale. Her hair pulled back in a chignon was silvery in the dim light; her ivory-colored dress, unadorned, fell in simple lines. He became aware of her breathing from its gentle motion. Her fingers rested on the edge of the tablecloth, as if to steady herself. Behind her, the band seemed muted. She nodded to both men but addressed only Mandelstam. Bulgakov expected him to compliment her appearance; the light of the room seemed to soak into her. But it wasn’t this that gave her an unworldly appearance. She had the air of the ill-fated; of one about to step from a platform onto empty tracks, the sound of a train filling the air. Not with the purpose to end her life so much as to embrace the monstrosity. He wanted to pull her to safety and at the same time to stand back and watch her proceed. He stood to give her his chair; she smiled a little, shook her head, and returned her attention to Mandelstam. He had remained seated.

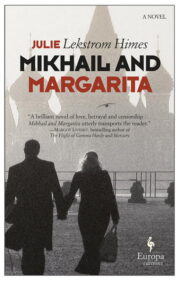

"Mikhail and Margarita" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Mikhail and Margarita". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Mikhail and Margarita" друзьям в соцсетях.