In the event, ten o'clock was striking the next morning as Arcadius, who had gone out well before daylight, returned to inform Marianne that the duel had taken place that very morning at the Pré Catelan. The two parties had fought with swords and had returned unreconciled, one, Chernychev, with a thrust through his arm, the other, Baron Kozietulski, with a wound in the shoulder.

'You need not pity him too much,' Jolival added, seeing Marianne's distressed face. The wound is not severe and it will have the advantage of saving him from a tour of duty in Spain, where the Emperor would most certainly have sent him. And don't worry, I will send to inquire how he does. As for the other…'

'The other does not interest me,' Marianne interrupted curtly.

The faintly sardonic smile which was Jolival's answer to this so offended Marianne that she turned her back on him without a word and went out into the garden. Why, she wondered, had her old friend smiled like that? What was he thinking? Did he imagine that she did not mean what she said when she declared that the Russian did not interest her? Did he think she was like all those other women who had fallen such easy victims to the handsome Cossack?

She strolled a little way along the sanded paths, all leading to the little pool with its murmuring fountain. It was a small garden, made up of no more than a few lime trees and masses of roses basking in the summer sun. The fountain was also small, in the form of a bronze dolphin clasped in the arms of an enigmatically smiling cupid. It was certainly nothing to compare with the marvels of the Villa dei Cavalli. Here, no proud stallion made the ground echo at night to the thunder of his furious galloping hooves, no phantom rider streaked through the shadows on his lonely way, carrying with him to the end of the night some terrible secret, some awful despair. Here, all was peace and cheerfulness, ordered, companionable, as a small Parisian garden should be.

The cupid on the dolphin smiled through the shower of falling crystal drops and it seemed to Marianne that she read a kind of irony in his smile. 'You are mocking me,' she thought. 'But why? What have I done to you? I believed in you and you betrayed me cruelly. You have never smiled at me except to take away what you have given. I entered into marriage as other women enter religion, yet you made marriage nothing but a mockery to me. And yet, here I am, married for the second time, and still as lonely. The first was a villain, the second is no more than a shadow – while the man I love is merely another woman's husband. Will you never have mercy on me?'

But no, the cupid remained silent and his smile did not change. With a sigh Marianne turned her back and went to sit down on a bench of mossy stone where a climbing rose dropped its crimson petals. Her heart felt empty, like one of those deserts created in a night by a hurricane gust of wind, carrying everything away with it, obliterating even the memory of what was there before. And when she tried to revive the fire that was slowly going out within her by remembering the madness of her love, the delirium of joy, the blind despair which the very name, the very picture of her lover had once had power to evoke. Marianne found to her distress that not even the echo of her cries remained. It was as if – yes, it was as if it were a story she had heard, but a story of which someone else was the heroine.

From a great distance, as though at the end of a long series of vast, empty rooms, she seemed to hear Talleyrand's persuasive voice saying: 'This was never made to last…' Could he have been right, after all? Was he proved right already? Could it be that her great love for Napoleon was dying, leaving behind it only the small change of tenderness and admiration that remains after the burning, golden flood of passion has withdrawn?. The present day Place de l'Italie.

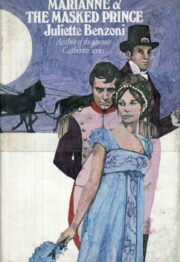

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.