'I hope he will not make me wait too long! Of course I want a boy. I hope you will give me a fine boy, also. We will call him Charles, if you agree, after my father.'

Marianne was dazed. He was talking of children now, and as naturally as if they had been married for years. She had a perverse urge to contradict him.

'It may be a girl,' she said. It was the first time such a possibility had occurred to her. Until then, she had always been convinced for some reason that the coming child would be a boy. But tonight it was quite impossible for her to put him out of temper. He answered gaily.

'I should be delighted to have a girl. I have two boys already, you know.'

'Two?'

'Why, yes. Young Leon, who is some years old now, and little Alexandre, born last month, in Poland.'

Marianne was silent at this, more deeply hurt than she cared to show. She had not been aware of the birth of Marie Walewska's son and she was inexpressibly shocked to find herself put on the same level as the Emperor's other mistresses, her child placed firmly in a kind of nursery for imperial bastards.

'Congratulations,' she said grittily.

'If you have a daughter,' Napoleon went on, 'we will call her by a Corsican name, a pretty name! Letizia, like my mother, or Vannina – I like those names! Now, hurry up and get dressed or people will start to wonder at the length of this audience.'

Now he was worrying what people would say! Oh, he had changed, he had thrown himself wholeheartedly into his role of married man! Marianne dressed herself with angry haste. He had left her alone, perhaps out of gallantry but more probably because of his own impatience to be back in his office. He merely told her to come down when she was ready. Marianne's haste was as great as his. She was eager now to be gone from this palace where, she knew in her heart, a perilous rift had occurred in her great love. She would find it hard to forgive him for this hurried interlude.

When she returned to the office, Napoleon was waiting for her, her shawl over his arm. He settled it tenderly about her shoulders, asking in a voice that was suddenly coaxing, like a child asking to be forgiven: 'Do you still love me?'

She merely shrugged and smiled a little sadly.

'Then, ask me for something. I want to make you happy.'

She was about to refuse when all at once she remembered something Fortunée had told her the night before, something which was much on her mind. Now or never was the moment to do something for her most faithful friend, and also to annoy the Emperor a little. Looking him very straight in the eye, she gave him a wide smile.

'There is someone you could make very happy through me, sire.'

'Who is that?'

'Madame Hamelin. It appears that when the banker Ouvrard was arrested in her house, the men also arrested General Fournier-Sarlovèze who chanced to be in the house.'

If Marianne had hoped to annoy Napoleon, she had succeeded abundantly. The smiling face of a moment before was instantly transformed into the mask of Caesar. He did not look at her but turned back to his desk, saying curtly:

'General Fournier had no business to be in Paris without permission. His home is Sarlat. Let him stay there.'

'It would seem,' Marianne said, 'that your majesty is unaware of the ties of affection which exist between him and Fortunée. They are deeply in love and —'

'Rubbish! Fournier is in love with every woman he meets and Madame Hamelin is besotted about men. They can perfectly well do without each other. If he was in her house, there was probably some other reason for it.'

'But of course,' Marianne said blandly. 'He desires quite desperately to be restored to his place in the army, as your majesty well knows.'

'I know he is a troublemaker, a mischievous hot-head – and one that hates me and will not forgive me because I wear the crown.'

'But one that dearly loves your glory,' Marianne said softly, astonishing herself by her ability to produce arguments in favour of a man whom she personally detested. But Fortunée would be so happy.

Napoleon's eye was turned on her in sudden suspicion.

'This man – how do you come to know him?'

A devil came to tempt Marianne. What would he do if she were to tell him that on the night of his august nuptials, Fournier had tried to ravish her behind a garden gate? No doubt he would be furious, and his rage would repay her for many things, but Fournier might well pay with his life or by perpetual disgrace, and he had not deserved that, however odious and impossible he was.

'Know him would be rather too much to claim. I saw him one evening at Madame Hamelin's. He had come from Périgord to beg her to intercede for him. I did not stay long. I had the impression that the general and my friend were anxious to be alone.'

The Emperor's shout of laughter told her she had succeeded. He came to her and took her hand, kissed it and, still holding her, led her to the door.

'Very well! You win. You may tell that urchin in petticoats that she will have her handsome cockerel back soon. I will have him out of prison and he shall have his command again before the autumn. Now, be off with you. I have work to do.'

They parted at the door, he bowing slightly, she sinking once again into the deep, formal curtsey, as stiff and impersonal as if nothing had occurred behind that door but a polite conversation. Marianne found Duroc waiting in the Apollo gallery to escort her to her carriage. He held out his hand.

'Well? Happy?'

'Extremely,' Marianne said in a tight voice. The Emperor was – charming!'

'The whole thing has been a complete success,' the Grand Marshal agreed. 'You are wholly restored to favour. You do not yet know how far! But I can tell you that you will certainly receive your appointment before long.'

'My appointment? What appointment?'

'As lady-in-waiting, to be sure! The Emperor has decided that as an Italian princess you will join the group of great ladies from foreign countries who are now attached to the Empress's person in this capacity. It is your right.'

'But I do not want to!' Marianne cried helplessly. 'How dare he do this to me? Attached to his wife, obliged to serve her, keep her company? He is mad!'

'Hush!' Duroc spoke hastily, casting an anxious glance around him. 'Do not fly into a panic. The appointments have already been made but, for one thing, the decree is not yet signed, although Countess Dorothée has already taken up her post; and for another, if I know anything of the Duchess of Montebello's exclusiveness, your duties will not take up much of your time. Apart from grand receptions, at which you will be obliged to attend, you will see little of the Empress, you will not enter her bedchamber, or converse with her, or ride in her carriage. It is, in fact, largely an honorary appointment but it will have the advantage of silencing busy tongues.'

'If I am obliged to have a post at court, could I not have been given to some other member of the imperial family? Princess Pauline, for instance? Or, better still, the Emperor's mother?'

At this, the Grand Marshal laughed quite openly.

'My dear Princess, you don't know what you are saying! You are a great deal too pretty for our charming, scatterbrained Pauline, while as for Madame Mother, if you want to die a speedy death of boredom, then I advise you to join the company of grave and pious ladies who make up her entourage.'

'Very well,' Marianne said with a sigh of resignation. 'I admit defeat once more. I will be a lady-in-waiting. But for the love of heaven, my dear Duke, do nothing to hasten the signature of that decree! There will be time enough.'

'Oh, with a bit of luck, I can drag it out until August, or even September.'

September? Marianne's smile returned at once. By September her condition would be sufficiently obvious to excuse her from appearing at court since, according to her calculations, the baby should be born early in December.

They had reached the steps and Marianne extended her hand impulsively for the Grand Marshal to kiss.

'My dear Duke, you are a darling! And, and what is more to the point, a very good friend.'

'I preferred your first,' he told her, with a comical grimace, 'but I will be content with friendship. Good-bye for the present, fair lady.'

The sun was setting in a blaze of orange light that made the sky behind the hills of Saint-Cloud seem on fire. The promenade de Longchamp was full of people, a gay, colourful crowd of gleaming carriages, handsome men on horseback, light-coloured gowns and brilliant uniforms. The evening was so mild that Marianne was glad not to hurry home. She was trying out a new carriage that day, an open barouche which Arcadius had ordered as a surprise for her homecoming. With its green velvet cushions and gleaming brass-work, it was both luxurious and comfortable. This splendid equipage attracted a good deal of notice, as also did its occupant. Women stared curiously, and men with an admiration divided equally between the ravishing young woman who reclined on the cushions and the four snowy Lippizaners handled with superb aplomb by Gracchus, glowing with pride in his new livery of black and gold.

Marianne lay back, lulled by the gentle movement of her carriage, and breathed in the warm air, heavy with the sweet scent of acacia and chestnut trees in bloom. Her dreamy gaze took in just enough of the brilliant, passing throng to enable her to recognize a face or return a bow.

At one point, however, the two lines of vehicles were brought to a halt to allow a passage to the numerous retinue of Prince Cambacèrés. During the enforced halt, Marianne's wandering attention was caught and held by a man on horseback who stood out oddly in the colourful crowd. Riding a beautiful chestnut at a gentle trot along the grass track beside the road, he seemed to take no notice of the blockage, merely bowing from time to time to one of the many women, who all smiled at him.

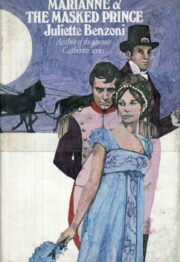

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.