Marianne could tell from his dark-green uniform with red flashes, from the Cross of St Alexander on his high collar and the peculiar shape of his black cocked hat with its cockade, that the man was a Russian officer, although the Cross of the Legion d'Honneur gleamed on his breast.

He was a superb horseman. That much was clear from his easy seat, combining gracefulness with strength, and from the muscular thighs, beautifully moulded by white buckskins. His figure, also, was distinctive: his shoulders were extremely broad but his waist as slim as a young girl's. The most extraordinary thing about him was his face which was very fair with narrow side-whiskers that grew like faint slivers of gold on his cheeks. The features had the absolute regularity of a Greek statue but the eyes, set at a slant, were fierce and of an intense green which betrayed Asiatic blood. The man had some Tartar in him. He was coming towards Marianne's carriage and as he neared it, he rode more slowly.

At last, he stopped altogether, only a few paces away from Marianne, but it was to look curiously and with great attention at her horses. He examined each one carefully, from head to tail, moved slightly back to study the effect as a whole, and then edged closer again. Then his eyes turned to her. The same procedure was repeated. The Russian officer sat his horse two yards away, inspecting her with the attentive look of an entomologist discovering some rare insect. His eye roved in insolent appreciation from her thick, dark hair to her face, already flushed deep red, to the slender column of her neck, her shoulders and her breast, which Marianne hastened to cover with the black and gold cashmere. Bursting with indignation and feeling unpleasantly like a slave put up for sale, Marianne tried to annihilate this unmannerly individual with her glance, but, lost in his contemplation, he seemed not to notice it. More, he actually extracted a glass from his pocket and put it to his eye the better to scrutinize her.

Marianne leaned forward hastily and dug the tip of her sunshade smartly into Gracchus's arm.

'I do not care how you do it,' she said, 'but get us out of here! This person seems determined to stay where he is until Judgment Day.'

The youthful coachman glanced over his shoulder and grinned.

'It would appear your Serene Highness has an admirer. I'll see what I can do. In fact, I think things are beginning to move.'

The long line of carriages was indeed beginning to move again. Gracchus flicked the reins but still the Russian officer did not stir. He merely turned slightly in the saddle so as to follow the carriage and its occupant with his eyes. This was enough: 'Boor!' Marianne flung at him.

'Don't you upset yourself, Highness,' Gracchus told her. 'He's a Russian and everyone knows Russians don't know what's what. They're all savages. I dare say that one doesn't speak a word of French. It was his only way of telling you he thought you were beautiful.'

Marianne said nothing. There could be no doubt of the man's ability to speak French. The language was part of the normal education of all noble Russians and this one was evidently not born in a hovel. He was a thoroughbred, for sure, but his behaviour merely went to prove that it was possible to belong to the Russian nobility and remain horribly ill-bred. Oh well, she told herself, the important thing was to have got rid of him! It was lucky he had not been going her way.

But when her carriage passed through the handsome triple iron gate of the Porte Mahiaux she heard her coachman say casually that the Russian officer was still there.

'What? Is he following us? But he was going towards Saint-Cloud?'

'Maybe he was but he's not going there now. He's right behind us.'

Marianne looked round. Gracchus was right. The Russian was there, a few yards behind, following the carriage as calmly as if that had always been his place. When he saw her looking at him, he even had the audacity to give her a beaming smile.

'Oh!' Marianne cried aloud. This is too much! Spring 'em, Gracchus! As fast as you can!'

'Spring 'em?' Gracchus said in horror. 'We'll have someone over if I do.'

'You can avoid them. Spring them, I said. Now is the time for those horses to show their paces, and you your skill!'

Gracchus knew that it was useless to argue with his mistress when she spoke in that tone. The whip cracked. The carriage set off at a spanking pace along the route de Neuilly, traversed the place de l'Étoile, and thundered down the Champs Elysées. Gracchus, standing up on his box like a Greek charioteer, shouted out warnings with the full force of his lungs whenever he perceived a pedestrian. All these, indeed, stopped in their tracks and stared, spellbound, at the sight of the smart barouche tearing past, drawn like the wind by four snow-white horses, with a horseman riding hell for leather in pursuit. The Russian's quiet following after the carriage had turned into a mad race. When the officer saw the barouche break into a gallop, he set spurs to his horse and set off in enthusiastic pursuit. His cocked hat was gone but he showed no sign of caring. His fair hair streamed in the wind as he urged on his mount with barbaric cries that matched Gracchus's shouts. It was not a sight to pass unnoticed.

With a thunderous roar, the barouche swept over the Pont de la Concorde, and rounded the corner of the Palais du Corps Législatif. The Russian was gaining on them, and Marianne was almost bursting with rage.

'We'll never shake him off before we reach the house,' she cried. 'We are nearly there.'

'Don't lose hope!' Gracchus yelled back. 'Help is coming!'

He was right. Another horseman was converging on their path, a captain of Polish Lancers who, seeing the smart barouche evidently pursued by a Russian officer, instantly decided to intervene. Marianne watched with delight as he cut across the Russian's path, forcing him to stop in order to avoid a collision. Gracchus's hold on the reins slackened instinctively and the carriage began to slow down.

'My thanks, monsieur,' Marianne called out, while the two men faced each other with obvious hostility.

'A pleasure, madame,' the lancer responded gaily, raising a gloved hand to his hat. A moment later, the same hand was applied to the Russian officer's cheek.

'That looks like the beginnings of a nice little duel.' Gracchus observed. Well, a sword thrust is a lot to pay for one smile.'

'Suppose you mind your own business,' Marianne snapped back. 'Take me home quickly and then come back and find out what has happened. Try and discover who both these gentlemen are. I will do what I can to prevent the duel.'

In a very few moments, she was standing in the forecourt of her own house, having despatched Gracchus to the scene of the quarrel. But when he returned not many minutes later, her young coachman could tell her nothing more. The two parties to the quarrel had already disappeared and the small crowd attracted by their altercation had melted away. Fearing the incident would attract a good deal more notoriety than it deserved and might even reach the Emperor's ears, Marianne did what she had always done in such a case and waited for Arcadius to come home to confide her troubles to him.

When he returned, Arcadius found himself entrusted with a confidential mission to prevent an absurd duel between a Russian and a Polish officer. This mission he accepted with his twinkling smile, merely asking Marianne which of the two adversaries she preferred.

'How can you ask!' she exclaimed. The Pole, of course! Didn't he rescue me from a man who was molesting me, at the risk of his life?'

'My experience of woman, my dear,' Arcadius retorted calmly, 'has not shown me that rescuers inevitably receive the gratitude they deserve. It all depends on who has done the rescuing. Take your friend Fortunée Hamelin. Well, I would stake my right arm that not only would she have felt not the faintest desire to be rescued from your pursuer, but she would actually have regarded any man who was fool enough to try it as a deadly enemy.'

Marianne shrugged.

'Oh, I know. Fortunée adores all men in general and anyone in uniform in particular. She would think a Russian a great prize.'

'Not all Russians perhaps, but this one, most certainly.'

'Anyone would think you knew him,' Marianne said, staring. 'Yet you did not see him, you were not there.'

'No,' Jolival agreed pleasantly, 'but if your description is correct, I know who he is. Particularly as Russians who wear the Legion d'Honneur are not exactly two a penny.'

Then who —?'

'Count Alexander Ivanovitch Chernychev, Colonel of Cossacks of the Russian Imperial Guard, aide-de-camp to his majesty Tzar Alexander I and his customary emissary to France. He is one of the finest horsemen in the world and one of the most inveterate womanizers of two hemispheres. Women adore him.'

'Do they? Well, not this one!' Marianne cried, reacting with fury to Jolival's complacent introduction of the insolent rider of Longchamp. 'If this duel does take place, I hope very much that the Pole will skewer your Cossack as neatly as a tailor sewing thread. Attractive or no, his manners are atrocious.'

'That is what pretty women generally say of him the first time. It is odd, though, how often they tend to change their minds later on. Come now, don't be cross,' he added, seeing her green eyes grow stormy. 'I will go and see whether I am able to prevent a massacre, although I doubt it.'

'Why?'

'Because a Russian and a Pole have never yet been known to renounce such a splendid opportunity for killing one another.'

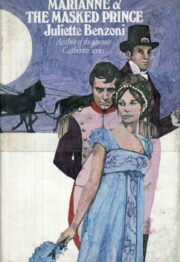

"Marianne and The Masked Prince" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Marianne and The Masked Prince" друзьям в соцсетях.