‘You have just proved that you lack faith in the Lord,’ he says brusquely. He looks at the girl and at me as if there is something repugnant about us. ‘That was wicked of you, a bad example to your classmates. And it is also most ungrateful to the people here who have taken you into their homes so lovingly. If anything like this should ever happen again,’ he sticks his hands into his brown dustcoat and nods curtly, ‘then I shall feel obliged to talk to your foster parents about it.’ He gives an angry cough. ‘That’s all for now. But don’t you forget it.’

We slide out of our desks and disappear from the room. The girl’s reproachful gaze is red and tear-stained now. We say nothing to each other and walk across the playground and up the road without a word. I look for Jan.

Warmth seeps down between the branches of the trees, and I breathe in the strong summer smells: grass, dung and fat, well-fed cattle. The light is dazzling. Meint is standing at a corner waiting patiently for me. I run up to him with relief: the first sign of brotherhood!

Chapter 5

Dear Mummy and Daddy,

Best wishes from Friesland. We got here all right and it was a nice journey. I’m fine, and being well looked after.

I am with a family with seven children.

Five of them are at home. The oldest daughter works on a farm near here. She lives there too, but sometimes she comes round here. She is very nice.

They have a little brother but he doesn’t live at home either. He had to be boarded out with another family when one of the girls here got polio. After that the family refused to let him come back home because they’d grown too fond of him. Isn’t that strange?

I eat a lot, plenty of everything. They want me to grow big and fat. Tonight we’re having a duck that got caught in Hait’s nets. Oh, I forgot, the father here is a fisherman. He goes out to sea every day in his boat.

I call the father and mother here Hait and Mem, that’s Frisian. Luckily I knew that from Afke’s Ten and other books I got out of the library. Frisian is a very difficult language. When they talk to each other I can’t understand a thing.

Jan Hogerforst lives around here too. There is a large farm and that’s where he works. I can see his farm from here, far away in the distance. We are good friends and often play together. I’m glad he lives close to me, because now I can visit him a lot. We talk about home. Jan says that Amsterdam is a long way from here, but that isn’t true because I looked it up in the atlas at school. If I got into the sea at Laaxum, all I’d need to do would be to swim across at an angle, and I’d be back home with you.

If it lasts for a very long time, the war that is, then we’ll escape from here. Jan has it all planned, how to get back to Amsterdam. That’ll be a surprise for you, won’t it?

Jan is the nicest boy I know, and so is Meint (my Frisian brother).

Jan hardly ever goes to school. I do. It’s a good half hour’s walk away, in a different village, and if we have to go back in the afternoon as well we walk nearly two hours a day.

School isn’t difficult. I can keep up with everything easily and we hardly ever get any homework. The master is very nice and is pleased with the way I’m getting on.

They use oil lamps here, and the water comes from a pump. There are sheep here as well and in the mornings before we go to school we have to clear up their droppings.

And I also have to make butter, in a bottle. You have to shake the milk for a very long time until it gets thick.

We have a rabbit and yesterday Meint and I had to take it in a sack to another rabbit. They had to be put together in a hutch and tomorrow we’ll fetch ours back.

I’ve lost my registration card, and the coupons as well. Is that going to get you into trouble?

The weather is fine and we often play outside. By the harbour is best. I help quite a lot with the nets as well. They stink of fish. Luckily we don’t get all that much fish to eat.

How are you? Did Mummy bring a lot of food back with her? I hope so. Just as soon as the war is over I’ll be coming back to you.

I miss you.

P.S. I sleep in my underwear, you have to here.

I seal the envelope carefully. I’ll post it tomorrow on my way to school.

I didn’t say anything about my little brother, nor about my wetting my bed.

Chapter 6

I don’t know why, but Sundays are the hardest. On the one hand it’s all very nice: Sunday breaks the dull monotony of ordinary weekdays and is the only day when the constant bustle in the house lets up for a little bit, as if all of us need a chance to get our breath back.

But it is difficult to say whether or not that makes up for church and Sunday school. Some Sundays are downright awful, but on others I get the feeling that I am being nicely uplifted and helped to look at everything through different eyes. When that happens, I step out of the church service with a lovely feeling, as if wings were growing under my shirt: God is merciful and everything will turn out fine in the end, including even me!

At meals we all sit down together, and most weeks Trientsje, the daughter who works at the farm, comes back home on Saturday evening and spends the night. She is like a gentle, warm-hearted mother, smoothing away all the sharp corners of my life. I can feel her deep care and concern, ‘Jeroen, have you had enough to eat?’ ‘Don’t fret, things at home are certain to be going well.’ ‘Meint, leave the boy in peace just for once!’

On Sunday morning we are all allowed to get up a little later. Hait stays in bed the longest of all, so we speak in hushed voices and tread cautiously through the room. The girls lay the table without a sound and cut the doughy wartime bread into crumbling, crustless slices untidily arranged on a shiny white plate. Mem brings a wooden board up from the cellar with a piece of cooked ham on it and a stone dish with a wet and sagging sheep’s cheese she has made herself.

Everyone is wearing their Sunday clothes, neatly creased and smelling of camphor. We are all scrubbed clean with slicked-down hair, spick and span, as if we were waiting to pose for a family photograph.

I am wearing Meint’s clothes because Mem says that the things I brought with me from Amsterdam are unsuitable for going to church. ‘Much too gaudy.’ I sniff at the sleeves: moth balls, sheep’s cheeses and God, all of them go inseparably and solemnly together, it is the smell of Sunday.

We wait around the table, my eyes travelling greedily over the mouthwatering display of food. My first dislike of fatty things has made way for a kind of gluttony. We wait for Hait, no one touching anything. He comes through the door, glossily shaved. Because he does not put his shirt on until just after breakfast, he is in his vest, his thin yet strong arms sticking out of the short sleeves. He closes the door with care and takes time to survey us all with a gentle smile. This is the first rite of Sunday, the return of the father to partake of our food with us.

‘Right, children, eat up now.’

With an approving look he watches his oldest daughter handing out the slices of bread and pouring tea from a grey enamel kettle. Grace has descended, it seems, I can feel it deep down inside me.

Mem sits with her arms folded across her heavy breasts. This is her free morning and she radiates contentment because of it. Every so often she shifts her false teeth about a little, her way of signalling that all’s well with her world and that she is allowing herself to drift away into pleasant reveries. Fascinated, I watch out for the moment when she pushes her lower teeth out, for then it looks just as if she were sticking her tongue out at us and smirking at the same time. Whenever she catches me spying on her like this she nods at me with her head on one side and closes her eyes for a moment. For all I can tell, she is winking at me.

That’s the best thing about Sunday, Mem’s transformation: he turns into a benevolent and uncomplaining mound of peacefulness from which all the furious weekday wrangling has slipped away.

After breakfast we go to church with Hait, the girls carrying hymn books, the boys walking in front, side by side. When we are in the road opposite the house, we wave to Mem who, large and dark, fills the whole of one of the windows and raises a languid arm, as if we were a ship that has put out to sea leaving the safe harbour behind.

In Hait’s company the walk to the village seems much shorter. He tells us stories about where he used to work and points out who lives where. If Pieke comes along, Jantsje pushes the disabled girl along on the bicycle next to Hait while lie tells her stories and makes jokes.

We wait among the people in the church porch to be let in. I inhale the smell of their Sunday clothes and the eau de cologne of the older women, trying to keep close to them for as long as possible because the smell reminds me of the time my grandma came to visit us in Amsterdam, when she would open her handbag and give me an acid drop.

Going into the church makes my heart and my throat throb, as if I am about to go on stage. To the low humming of the organ I walk up the aisle, my hands crossed reverently in front of my stomach. If, as I move past, I catch the eye of I people already seated in their pews, I nod to them gravely and they nod graciously back, while the prelude-playing organ fills the church with a familiar sense of fellow-feeling. I have the impression that I have been singled out to do something heroic, God looking down on me from the heights and thinking, ‘Any minute now I shall work a miracle through him.’ Gooseflesh shoots across my arms and back and my neck tightens with suspense. We slip into one of the pews. There are small cushions lying about and at every place there Is a black hymn book. I look up to see if I can spot Hait who had disappeared outside across the churchyard and round the back of the church. Trientsje opens her psalter for me and places it silently on my lap. She points with a stiff, proud finger to the words scribbled in the front: ‘For my daughter Trijntje. On her sixteenth birthday. Hait.’

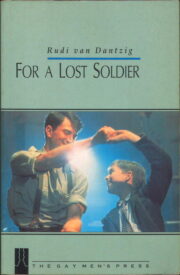

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.