The low building has just four classrooms, tall, stark places with grey-painted walls, no pictures or drawings, nothing.

Plain and empty.

The windows start high up the walls and the window-sills are bare. It is as if everyone abandons this place as quickly as possible after school. I think of our White School in Amsterdam, the sun and the plants which the teacher carefully tends, pinching out the overblown flowers.

I stop at the door and watch as the schoolmaster comes in and walks up to the window. He tugs at a rope and a small window at the top swings open with a big bang. I catch my breath. He beckons me imperiously with a crooked finger and points to a seat at the back. In front of me I see Meint’s familiar head. There are some eight or ten children in the class, each with a desk to himself. It’s a strange school: between the two classrooms is a door that stays open so that the master can give lessons to two classes at once. I hear his voice through the door, and another window being swung open. When we pray – the master standing in the doorway, head bowed – the silence of the village floats in over us through the open windows. The class is taking dictation while I look on. There is a girl who isn’t doing anything either, I know her from the lorry. You can tell from her clothes that she’s from the city because her dress is colourful and gaudy in comparison with the other girls’. It’s just as if she and I were wearing our Sunday best for school. Now and then she gives me a reproachful look. I’d like to get to know her, but have no idea how to set about it. Should I give her some sort of sign perhaps?

The master delivers his lesson slowly and drowsily, there seems no ending to it. The incomprehensible sound of his voice makes me tired and I try to smother my yawns and pretend to be looking for something in the little locker under my desk.

We troop outside in small, silent groups. Break. There is no shoving, no shouting, no laughing. Everything is orderly and grown up.

We walk up and down the yard for a while, some walking with the master, others waiting patiently by the school wall until they can go back in.

There are no houses behind the school, you can look right across the fields as far as the sea-dyke. I can see the hilltop of the Cliff rising upwards. The bleak landscape, open and without secrets, the emptiness blowing in to meet you.

When we go back into the classroom Jan has suddenly, mysteriously, appeared out of nowhere. I leap up at my desk and try excitedly to attract his attention. Jan is my mainstay, the two of us together will be able to run away from here and get back home. And if we come across Greet)e from Bloedstraat we can take her along too. I can just see it, three children roaming through the countryside in search of their home. Like in a book.

Jan is put at the desk in front of me. His self-assured eyes glance briefly in my direction, but there is no recognition in his look or pleasure at our unexpected reunion.

T think all the evacuees are here now,’ says the master. What has happened to the rest, I wonder, where have they got to? Swallowed up in the far reaches of these lonely parts? We have to write down our names and ages on a piece of paper and the names of the families who are putting us up. Without so much as glancing at them, the master puts the papers on his table and goes through into the other class.

To the amazement of the others in the room, Jan immediately turns around in his seat. He smiles at me and starts to talk. I shrink back and signal ‘sh!’ with my finger. We mustn’t draw attention to ourselves straight away. That could ruin our plans.

‘What a filthy walk it is to this place. I couldn’t find it at all at first. They won’t be seeing me here very often, believe me.’ He looks around the classroom. ‘Backward dump. What on earth do you think we’re going to learn here, not a lot, that’s for sure!’

I look at his insolent expression and jerkily-moving head. As he talks he puckers his freckled nose, and his tongue darts rapidly across his lips as if he is gulping something down.

‘I’m on a big farm. It’s great, lots to do. They’ve got two small children. I’m going to ask them to let me skip school. I’d much sooner help with the animals.’ He gives a snort. ‘Where have they stuck you? Here, in the village?’ He pulls me over towards him and whispers in my ear, ‘I’m sure you could come and stay with me. I’ll ask them at home.’

The master appears in the door and glowers into the classroom. His eyes are dull and disapproving. T can see three new faces,’ he says. ‘From the city, from Amsterdam. Perhaps you are all used to something else at school there, but here there is no talking during my absence. If you don’t understand something, you put up your hand. And I think…’ he seizes my collar and marches me to a desk at the very front, ‘I think it is better if you don’t sit too close together.’

His footsteps echo emphatically through the classroom. He draws the curtains to dim the sunlight which is streaming through the open window. ‘I take it you come from a Christian school?’

I make a movement with my head that I hope can mean ‘yes’ or ‘no’.

‘Where did we get to two days ago, Jochum?’

A boy with very short blond hair and dressed in blue overalls stands up. ‘Deutonomy, master.’

‘Good try, my boy. The Book of Deuteronomy. Moses’ last sermon.’ He reads out a piece from the book, keeps silent for a moment while he looks around the class, and says, ‘Moses is the Old Testament, Jesus the New. Which one of you can tell me the names of the Apostles? I ask because I would like to make willing apostles out of all of you, propagators of the Holy Word and of Our Lord’s Gospel.’

It is quiet in the classroom. I think of Jan, I want to turn around and look at his familiar face. The teacher’s finger points in my direction. ‘You over there, the new boy. What’s your name?’

‘Jeroen, sir.’

‘I’m no sir, we don’t have any sirs around here. I’m called master, so call me that in future, if you don’t mind.’ He looks for the paper on which I have written my name. ‘Oh, with the Vissers, in Laaxum,’ he reads out. ‘Lucky for you, boy, a fine family. Not so, Meint?’

Meint goes red in the face, his answer is hoarse.

‘Well, Jeroen, so you’ve been to a Christian school. Can you tell me the names of the Lord Jesus’ disciples then?’

In Amsterdam I went to Sunday school a few times round about Christmas time, because they used to give you some sweets and a small present. Sometimes I came home with a small coloured print that had a text written on the back. I had always stored such treasures away in a metal box for safekeeping. ‘Holy cards,’ Mummy had laughed, ‘we were given those too, once upon a time.’ I look around the classroom. The children are staring at me curiously, except for Jan who sits at his desk with a vacant smile, legs spread wide, his hands tightly gripping his bare knees.

I take a leap in the dark, as one might jump into the sea, nostrils pinched tightly together. ‘Joseph,’ I begin, for that is a name I remember clearly, ‘David, Moses, and Paul, uh…’ But that makes just four. Ought I to have added Jesus as well? I hear nervous sniggers and can see Meint looking down at the floor in embarrassment.

The master walks to the communicating door and says to the other class with a triumphant ring to his voice, ‘Jantsje, that new member of your family doesn’t seem to know very much. Can you tell him the names of the twelve apostles?’

From the other room, sounding hollow and as far away as the bottom of an echoing well, I can hear Jantsje’s light little voice smoothly reel off a list of names. ‘And who betrayed Jesus?’

‘Judas, master.’ A chorus of voices.

I hope that Jantsje and Meint won’t tell on me at home. I am terribly ashamed, my ears are burning. Judas, I ought to have known that name. And curse my luck, right in front of the class. Now I’ll always be picked on first, you wait and see.

The master stands in the doorway between the two classes. ‘Let us pray.’ Uncertainly I fold my hands under the desk. I can feel the master watching me closely. It’s as if I were telling a lie just by folding my hands.

‘Oh Lord Our God,’ I hear, ‘we thank You for this morning, in which You have once again allowed us to be together. We beseech You, oh Lord, to bless us, and our new classmates also. And we beseech You, Lord, to bless the families of these children, families who are suffering hunger and want, who are sick and dying for lack of food, lack of succour and lack of hope. Grant this, oh Lord.’

Behind me, I can hear stifled sobs and I become aware of an achingly desolate feeling breaking loose inside me.

‘And who are suffering the blackest and most bitter circumstances. Remember them, Lord, and lend them Your infinite, never-ceasing strength and succour.’

It is beating up inside me in waves, slamming through me with deafening booms. It will not be held back. In jolting heaves the despair erupts from my mouth, my eyes, my nose, retching waves of dribbling, snivelling sorrow. I am like some alien invalid, someone who no longer has control over his body and is in the throes of grotesque and humiliating convulsions. I can hear my sorrow raging through the astonished silence of the classroom.

‘You two stay right where you are.’ I can tell that the master is speaking in my direction. ‘The rest of you may go.’

Now the master will give me a friendly and understanding talk, he will console me and tell me that it won’t be as bad as all that, that Amsterdam will be spared sickness, hunger and death. And he’ll forgive me for the apostles as well. The master stands right in front of me. In vain I wipe my nose on my sleeve but the snot keeps on coming.

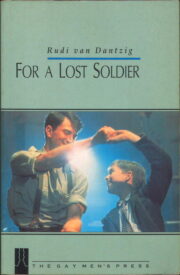

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.