Half an hour later the father holds a wildly wriggling eel between his fingers. With one deft movement he cuts off its head, as you would snip a flower from its stalk. He throws the suddenly severed body into a bucket of water where to my horror, it continues to move. The bloody stump of a head disappears into a newspaper.

I turn round and walk away, but a moment later I am back squatting by the bucket again, staring at the desperately writhing mass of pain.

I stand shivering in the little shed, waiting to wash in a tub the woman has filled at the pump. When I had got up in the morning, she had first inspected the cupboard-bed suspiciously, patting the mattress with the flat of her hand. I felt deeply ashamed.

On my first night here she had opened two small doors in the living room to reveal a cupboard-like space fitted out as a bed, all safe and snug. When I was getting undressed and had started to take off my underwear, she had objected. ‘No, we keep that on here, else it’s much too cold. Just put your pyjamas on over them.’ It had felt strange, going to bed with two layers of clothes, one on top of the other.

Meint and I slept in the same cupboard-bed. I shoved over as far as possible towards the wall so that there was room between us. The small doors were closed, leaving just a chink. The voices in the room had sounded far off and yet very near, as if someone were mumbling into my ear. I thought of home, submerged under the bedclothes, immersed in warmth and hush, in the grip of thoughts that kept me from sleep. And yet this had been the happiest time of the whole day: I didn’t have to say anything or see anybody. I lay tucked away safely in the dark and for the time being no one was going to come and take me away. This warm spot was where I belonged.

The three girls sleep in the cupboard-bed next to ours, the other one in the corner by the small window is for the parents. ‘You’ve got Popke’s place,’ Meint said, ‘he’s better off sleeping up in the loft. There’s more air up there.’

We listened to the voices in the room. Was Meint cross with me for taking his brother’s place? I tried to tell from the sound of the whispering voice which cracked hoarsely and huskily. ‘I’ve got to go to school tomorrow. You’re to come too, Hait says. We’ve only just started again.’

School… It had never occurred to me that I would have to go to school here as well, that the teaching, the testing, and the homework would go on as usual, unchanged, just like at home.

When the light in the room went out – the woman gave a noisy blow and I smelt the penetrating oil fumes that cut sharp as a knife through the dark – I could hear, besides Meint’s breathing and the creaking from the other cupboard-beds, the wind sucking along the walls of the house, a persistent, swelling, threatening noise. I was lying in a little boat that was being tossed about on strange seas, slipping through dark tunnels and tacking across unfathomable deeps, moving further and further away from the familiar mainland.

I woke up with a start in the night. It took a little time before I knew where I was. I had dreamt of home: my mother was sitting bent over forward in a corner of the room, her face buried in her hands. My father was standing by the window and I was suspended just outside, floating in the air. He was trying to get hold of me, but whenever his hands nearly touched me, I swerved away. ‘You must get in Frits’s car,’ he shouted, and I could see that ‘Frits’ was down below in front of the door, hanging out of the car window and gesturing upwards, grinning. My mother dashed out onto the balcony, hauled me in like a balloon on a string and wrapped her arms around me protectively. The two of us were crying, and my Clothes gradually became soaked through…

I woke up with a start. A strange boy, breathing audibly as if short of air, was asleep next to me. It was cramped in the bed, the cupboard seemed filled with stale air: I had to get out or I would suffocate.

Through the chink between the small doors I could see a bit of the dark room, gleaming black and still. Something was wrong, but what? I touched my pyjama trousers and felt that I hey were wet. How was that possible, how could that have happened? My clothes were soaked, and feeling round me I discovered that the mattress, too, was damp. Without making a sound, I edged as close as possible to the wall to find a dry spot, and then cautiously, so as not to wake Meint, pushed my wet clothes down to my ankles.

Did you have to fold your hands when you wanted to pray, wouldn’t it work otherwise? I laced my damp fingers together: Please, God, let everything be dry by tomorrow.

But it isn’t dry next morning.

The woman turns down the bed while I stand guiltily by, one bare foot on the other. ‘He’s wet his bed,’ she calls out in horror. She smells the sheets and a moment later walks out of the room, her arms full of bedding, a disgusted expression on her face. ‘Do you do that at home all the time? You really should have warned me. Your mother could have sent a note, couldn’t she?’

No, I did not wet my bed at home. I had done it once for quite a long time, we had always kept it a secret, my mother and I, even from Daddy… But that must have been at least five years ago.

At breakfast I make myself as small as possible and I’m sure they are all giving me a wide berth, they are all disgusted with me. I get the feeling I shall never be able to put this right, that I have spoiled everything. Wetting the bed, not going to church, not praying aloud, losing my registration card – I really am a terrible failure.

‘What will become of you?’ my mother had often said when I came home with bad marks from school. ‘You’ll end up a pigswill man.’ Then I would take a good look at the stinking wagon that drove through our street at noon. Jute sacks hung down from the back of the cart, filled with something undefined and horrible, and oozing long dribbling sticky threads. The man who collected the baskets of potato peel wore pig’s wash-stained overalls and large rubber boots, as he sat, legs wide apart, on the box, slapping the skinny back of his horse with the reins. Would I be sitting up there next to him one day?

I wash my face over the tub, scrubbing desperately, but tears of humiliation keep coming.

For some reason or other I do not have to go to school that day. The woman is so annoyed that she doesn’t deign to glance in my direction, and Jantsje and Meint go off to their lessons without me. She tidies up the room in silence. I miss the father, but presumably he had gone very early out to sea.

I sit about on the chair by the window for a while, then trail aimlessly through the house. I am profoundly miserable. The morning seems as if it’s never coming to an end, but finally it is noon, everyone is back home again and there are large pans of food standing on the table. They all seem to have forgotten the bed-wetting, they seem even to have forgotten that I am here, they keep talking to each other and pay no attention to me. Right in the middle of the meal, I suddenly have to rush out to the w.c. behind the house. When Diet comes to see what has happened to me, she finds me slumped over sideways in the little wooden privy.

‘He’s got the runs,’ she says, leading me back inside. ‘He’d better lie down for a bit.’

From inside the cupboard-bed I can hear them muttering about me. ‘Townsfolk aren’t used to proper food any longer, they’ve hardly got anything left. His stomach has got to get used to it first.’ But the mother protests vociferously. She is convinced now that she’s been landed with a freak of a boy when what she’d asked for all along was a girl for her Pieke! Feverish, I doze off.

Chapter 4

In the morning the grass is silver and the dew makes my socks wet. Lifting my knees high, I walk through the meadow. Meint is standing by the gate, his hair standing up in unruly tufts, a crease from his pillow running across his cheek. It is a quarter past eight, my first school day.

‘You need clogs, man, shoes are no good around here.’ My shoes are shabby and down-at-heel, the wet leather speckled with grass seed. I stamp the seeds off on the road.

‘Aren’t you going to wave to Mem?’ asks the girl. I can see the woman standing behind the window and warily raise my hand to her. I know this twisting and turning road we’re on now. Two days ago, I passed along it on a bicycle, perched behind the stranger. A road of unending loneliness.

The farmhouses are large and self-contained, noble fortresses. Every so often the wind carries the smell of smouldering wood and the sound of voices from a stable. A woman walks through a farmyard and calls something to us in a piercing voice. Meint points out the cows looming up through veils of low-hanging mist, their backs suspended mysteriously, ghostlike above the ground.

During the walk, I have to stop a few times. My breakfast comes spurting out in slimy white clots that land back onto my clothes because of the wind. I bend over, with tears in my eyes, fretting with anxiety as Jantsje and Meint look on in amazement.

The school is still a long way off, more than half an hour’s walk. Sick to my stomach, I walk along the village street. We pass the church and suddenly I recognise a small structure.

‘The Sunday school,’ says Meint and Jantsje pulls a face. For a moment I look up hoping the lorry may still be there, tucked away in some corner hidden from view. Or maybe it will be coming back to deliver the next batch of children. I must keep an eye on this place, I mustn’t let any opportunity slip by.

There is a low building just past the crossroads with a small yard in front. Resignedly I follow Meint and Jantsje through the waiting children. There are curious glances and Meint looks proud: ‘He’s come from the city to live with us.’

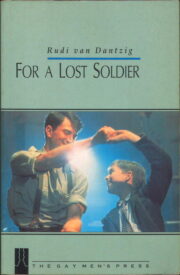

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.