I am sure that even the cows know that I am a stranger here, because sometimes one of them lifts her head and stares after me with round, moist eyes.

Without warning, the man suddenly stops in the middle of the meadows and gets off.

‘It’s a fair stretch,’ he says. I can hear he is doing his best to speak distinctly so that I can understand. ‘We’re making for Laaxum, by the sea. You’ll be lodging with fisherfolk, good people. But I’ve got to go back first, we’ve left your suitcase at the Sunday school.’ I stand all alone on the road, feeling as if I’ve been dropped from the moon. Fields of grass all around me and not a soul in sight.

This is a trap, of course, the man will never come back. I’ve been left here to starve to death, they meant me to all along. And my father was in it as well, that’s for sure. They want to get rid of me.

The man had said, ‘You’ll be lodging with fisherfolk.’ That was wrong for a start. My father had told me over and over again that we would be boarding with farmers, farmers with sheep and stables, haystacks, goats and horses. Like in the hooks I’d read at school. Fisherfolk? I have a nightmare vision of a ramshackle wooden hut on a wide, wind-blown shore with two old people sitting silently, continually mending nets. I can’t stand fish. I can’t get it down my throat, I’d sooner starve or choke to death! What am I doing here, why am I having to put up with all this? Where is my mother, where is our safe little home? And where have they taken Jan? If I knew where he was we might at least try to escape together. Shall I run back and try to find the driver? If I hurry, the lorry may still be in the village.

A spark of hope. I start racing back down the road like one possessed. The silence roars in my ears with every step I take. I have the taste of blood in my throat.

A cow lifts her head and lows loudly and plaintively. In the distance the man is coming back on the bicycle, my suitcase dangling from the handlebars. When, panting, I stop running, he looks at me in surprise, but asks no questions. I’ve been caught out and feel a little ridiculous. Shamefaced, I get back onto the luggage carrier.

We bicycle on, a road without end.

‘See that dyke at the end of the road? That’s where we’re going.’

I poke my head out from behind the man, but quickly pull back when I get the wind full in my face. I’ll be seeing it soon enough.

‘Off you get. This is Laaxum. We’re there.’

I take a look around and see empty, wind-swept countryside with little houses dotted about. Is this a village, this handful of tiny, scattered dwellings? The loneliness grips me and clamps my chest.

We climb over a wooden fence and wade through tall grass. A grazing horse takes a few snorting steps away from us and I quickly draw closer to the man. Another fence, and then to the little house on the left. No trees, no bushes, nothing. Emptiness.

At the back of the house is a stable-door, the upper half open.

‘Akke!’ calls the man. He steps out of his clogs and we go inside.

A large, heavily built woman in dark clothes, seemingly consisting of nothing but enormous round shapes, is bending over in a low room. When she draws herself up, the room looks too small for her. She has a strong face and immensely wide eyes. She walks to the table, drops into a chair and pins back a loose strand into her knot of hair. One of the Fates, as large as life, looking first at my escort and then at me and then bursting into loud and incredulous laughter.

‘Oh, heavens, it’s our war child.’ She looks me over from head to toe. ‘But we asked for a girl for our Pieke to play with.’ Her voice takes on an annoyed and threatening tone.

She stands up, filling the room with her bulk again, moving towards me: there is no escaping her.

‘Go and sit down there.’

I huddle into a chair by the window she points out to me.

Pasture-land outside, emptiness and wind. Inside it smells of food and burning wood. The man goes and sits down to talk at the table with the woman, conspirators speaking an incomprehensible language.

‘He goes to church, I take it?’ Suddenly the question is clearly comprehensible.

I say ‘yes’ quickly. A lie, but otherwise they might throw me out straight away. I’ll hand over the registration card with the ration coupons now. Maybe that’ll make her think a bit better of me. I feel in my pockets: empty. Frantically I look through all my clothes: it can’t be, I can’t have lost them?

The man gets up and holds out his hand to me. ‘They’ll look after you well here,’ he says, ‘as long as you eat up.’

Another familiar face going out of my life. I feel like excess ballast, shunted from one person to another.

The door rattles; I hear the man step into his clogs.

As he recedes into the distance the woman continues her conversation with him, shouting loudly over the fields as he disappears. Then the voices stop and all I can hear is clattering in the kitchen. Maybe the woman is never going to come back into the room again. Silence. A clock ticks behind me.

When she does come back in, my face is wet. She wipes my cheeks dry roughly with her apron, but her silence is friendly and considerate.

‘Ah, little one,’ she says putting my suitcase on the table, ‘are you tired? Would you like something to drink?’

I shake my head. She doesn’t seem cross any more that I’m not a girl, the ice has been broken.

She opens my suitcase. ‘Not very much,’ she says looking the contents over. But then she lifts up a towel and is full of admiration. ‘What a beauty.’ She holds it spread out in front of her. ‘All those colours. That must have cost a lot of money.’

I look at it: a little piece of home.

She sits down facing me by the other window and picks up a bowl of potatoes from the floor. ‘The others will be home soon, then we’ll eat.’ Her eyes bore into me.

The sound of the knife cutting through the potatoes and the ticking of the clock. The window-panes creak in the wind. I peer behind me: it’s only half past nine. Nervously, I take in the smells, the sounds and the shapes. Even time is different here, slow and dragging. Eternities seem to have gone by since yesterday.

My eyes fall shut and I wake in confusion as the woman drops a potato in the pan. I must stay awake, who knows what’ll happen to me otherwise…

A small wooden plate hangs on the wall facing me. ‘Where Love Abides the Lord is in Command.’ Love, I know that, and command as well. You give commands to dogs. Come. Sit. Down. The Lord must be God, of course, but…

‘How old are you?’ Again that inquiring look.

‘Eleven. I’ve just started the sixth year.’

‘Eleven. The same as our Meint. That’s good, the two of you can do your homework together.’

She walks out of the room and I follow her obediently. Outside she pumps water into a pan and throws the potatoes in. Then she puts the pan on the kitchen-range in a shed fitted up as a cookhouse. She throws logs on to the fire and pokes it hard. Sparks fly out into the open.

‘Does your mother cook on a stove as well?’

I nod ‘yes’, afraid she’ll send me away otherwise. I’ve made up my mind to agree with everything she says.

In my mind’s eye I can see my mother in a summery, bright kitchen, the veranda door open and me playing outside.

The woman’s large round back moves about steadily while she sweeps the stone floor. She pushes me outside firmly because I am in her way. Shivering with cold, I lean against the little shed and look at the dyke that runs from end to end of the horizon. I can hear the sea: somewhere beyond it lies Amsterdam.

When the woman goes back into the house I hang back, then walk meekly after her. I duck into the chair by the window and wait. The clock ticks insistently. Slowly I doze off and give a start when I hear the sound of voices outside the door. Suddenly they hush. A girl’s voice asks, ‘Is he in the room?’ I brace myself in the chair as the doorknob moves.

Chapter 3

We eat potatoes and meat. No greens. Two big pans stand on the table and the father does the serving up. Now and then somebody holds out a plate without saying a word, the big boy has had three helpings already.

I look around the circle. There are six children sitting at table, shoulder to shoulder, all of them fair, all of them sturdy and all of them silent. They eat hunched over forwards, as if it is hard, strenuous work. They have lost interest in me.

I feel hemmed in and small and try not to take up any room when making movements towards my plate. At strategic moments I take a bite quickly and as unobtrusively as possible, swallowing hurriedly. After a few bites my body feels tired and leaden, a wave of liquid rising up inside me and burning in my throat.

I clench my fingers around the edge of the chair and think of home.

More and more people had come clumping into the small room, first a boy and a girl my age, followed by a smaller girl with a limp. She had hobbled through the room, steadying herself against the table or the wall. Later a couple more came in who were older, Popke, a tall, weather-beaten boy – the only one to hold out his hand to me and to introduce himself – and a boisterous girl with sturdy breasts under her tight dress.

She had been talking noisily as she came into the room, but when she had seen me sitting there, she had suddenly fallen silent as if someone were sick, or dead.

They had all of them looked me over, a strange little boy in their house sitting there uncomfortably in a chair. After the first awkward silence, they started talking among themselves in undertones. Sometimes I could hear them stifle a laugh. When I glanced in their direction, one of the girls burst out laughing and ran quickly out of the room.

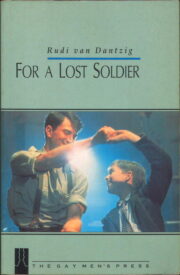

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.