By eight o’clock our street is jam-packed with children and their parents. There can be nobody left inside. From our balcony I can see men in blue uniforms – ‘Look, the Resistance,’ says my mother admiringly – small groups of girls walking arm in arm, lots of families from other streets, and, among the crowd, knots of soldiers drawing nonchalantly on their cigarettes and hanging about looking expectant.

‘Come on,’ says my mother, ‘it’s time we went downstairs. You must want to join the fun.’

I make a face.

‘There’s so much going on, surely you don’t want to miss anything? You don’t have to join in if you don’t want to, you can just stand there and watch.’

When we come out of the front door the crowd is thronging towards the other end of the street, the children running excitedly through the crush, shouting and pushing people out of the way, laughing exuberantly. I fall silent, my spirits dampened by their boisterousness, and as we join the motley stream of people I clutch my mother’s arm, longing to be back home. The street is like an empty swimming-pool with pennants hanging from long strings fluttering overhead in the wind. I walk along the bottom next to the tall sides and look for a way out.

At the other end of our street, close to the school, an apartment window on the first floor has been flung wide open, the windowsill draped with a flag and a few sad-looking daffodils with broken heads fastened to the woodwork.

Everyone is gathered under the window and looking up eagerly. The loudspeaker music stops with a loud click in the middle of a tune and the hubbub of voices in the street grows softer and dies away.

A man appears in the window, wearing a bow tie and with an orange ribbon pinned to his coat. His plump face is set and solemn.

‘Who is that man?’ I whisper to my mother.

How can anyone be so fat after the war? He must be someone very important.

‘Ssh. I don’t know either.’ She tugs at my arm and I shut up. The gentleman surveys the crowd with a haughty and satisfied expression. He is standing in front of a microphone which he taps a few times, making the loudspeakers resound with a series of drones and crackles.

‘Fellow countrymen,’ he cries. ‘Neighbours. Friends.’

Suddenly there is a piercing whistle, a high screeching sound that makes some people clap their hands to their ears. And there is suppressed laughter as well, which shocks me: how can they stand there and snigger so disrespectfully, what is there to laugh about anyway?

A few arms reach from out of nowhere to snatch the microphone away and there is more grating and booming.

Now my mother is laughing too…

‘Fellow countrymen. Neighbours. Friends. The enemy has been beaten, our nation has been liberated from the German yoke and our liberators’ – here he makes a sweeping gesture over the street – ‘are amongst us. Before very long our beloved queen and all her family will be joining us…’

He is holding a sheet of paper which, as I can see clearly even from below, is shaking in his hands as if caught in a stiff gust of wind. The flood of words roll over me, sounds whose meaning escapes me. When he folds up his paper there is a deathly hush, and then I hear the strains of a familiar tune.

‘Whose veins are filled with Netherlands blood…’ The man stands stiff as a ramrod in the window-frame, his stomach sticking out. Around me I hear more and more voices joining in the singing, hesitantly at first, then louder and louder.

‘Why isn’t he singing himself, Mum?’

The mood is subdued and solemn now and some people are dabbing their eyes. The song is over and the silence is unbroken. My mother looks at me from out of the corners of her eyes, nods at me encouragingly, then takes my hand and squeezes it hard.

A startled dog runs barking through the crowd, scattering a cluster of shrieking girls; a moment later I hear a loud, high-pitched whine as if someone has given the dog a kick.

‘Our neighbour Marietje Scholten will now oblige us with Schubert’s Ave Maria. Her father will accompany her on the piano.’

The gentleman bows, making way for the milkman’s daughter who takes his place at the microphone. Her cheeks are scarlet as she looks straight across the street with staring doll’s eyes, as if she does not see any of us and is standing up there against her will, about to burst into tears.

‘Are you ready?’ she asks, looking behind her into the room. When her question comes loud and clear over the loudspeakers, she gives an apologetic laugh and places her hands over the microphone. The crowd claps sympathetically as a few hesitant, searching chords become audible.

‘I want to leave now,’ I whisper, ‘can we go?’

The thronging crowd is stifling me, and I have the feeling that the girl will never get her song started; she has brought the microphone close to her petrified face, clutched in both hands, and still nothing is happening.

Then, all at once, she sings. I stand rooted to the spot: the sound of her voice and the music she sings echo deep within me, as if a stone is being turned over inside me. An ecstatic feeling of happiness and abandon soars up in me, growing all the time. My chest feels tight and I pull my hand away from my mother’s. I am being torn apart.

The people stand side by side listening in total silence, neighbours, soldiers, children, nobody moving. We have forgotten about the shrillness of the microphone, we are held captive by that voice, soaring over our heads into the night sky.

The applause ebbs away. Marietje bows awkwardly and knocks the microphone over.

‘What’s the matter?’ my mother asks, but I turn my face away from her furiously. ‘Darling,’ she says, ‘don’t be like that.’

I watch the rest of the celebrations from our balcony, the people standing in place by the white lines down the whole length of the street, craning their necks and jostling one another. Where the lines end, and someone has chalked the word FINISH in large letters, other people are crowded around the table with the prizes: a bag of flour, a few bars of chocolate, a packet of tea and some small bags of milk and egg powder.

Our next-door neighbour, apparently in charge of the competition, shouts, ‘Attention!’ and blows a whistle.

To the accompaniment of encouraging yells the competitors stumble, hopping and falling about between the white lines, their legs stuck inside jute sacks.

My mother, too, has joined in this grotesque parade. I don’t know whether to be proud or ashamed of her, and am in two minds about cheering her on. The bystanders call out names and urge the competitors on, and my father, standing beside me, whistles shrilly through his fingers.

‘Keep going, Dien, don’t wobble!’ but by then she has stopped and fallen into the arms of some bystanders, helpless with laughter.

‘You ought to have joined in as well,’ says my father, ‘why didn’t you, lazy-bones? Such fun and you could have won a bar of chocolate.’

I don’t answer and. watch my mother wriggle out of the jute sack still screaming with laughter. When a voice announces that the winners’ names are about to be called I try to slip inside unnoticed.

‘Hang on a minute, Jeroen, you want to hear who’s won, don’t you?’

What difference can it make to me, you can all do what you want, behave like little children if it pleases you, but leave me in peace.

‘Do you hear that? Jan has come third!’

But I am looking at a couple of soldiers who are disappearing over the grass bank along the canal, followed by two girls. They saunter to the edge of the water and sit down, so that I can see little more than their heads. One soldier puts his arm around a girl and they slide backwards into the grass, disappearing from sight.

The water in the canal is black and still, a few pieces of weed floating in it and a duck balancing on a rusty bicycle wheel that sticks above the surface. A glimmer of light from the gardener’s house on the other bank makes an oily reflection across the water.

I walk into my dim little room where the hubbub from the street sounds unreal. The house is empty, cavernous.

I bite my pillow and try not to think. I fold my hands between my tightly-squeezed legs and curl up small.

Please God, make him come back, make him find me. If You let him come back I’ll do whatever You want.

I am bicycling to Warns. I have no clothes on. Walt is sitting on the luggage carrier with his arms around me, stroking my belly.

I can see people everywhere, behind windows, in gardens, on the pavements and ducking around corners. I pedal like one possessed but the bicycle hardly moves. I sweat under the firing squad of prying looks. I gasp and struggle on. Mem stands in front of the house, crying and beckoning me with her dependable, stout arms. I can’t reach her. I pedal and pedal.

‘Move,’ Walt whispers, ‘move. Go on, faster.’

His fingers caress my stomach and I feel ashamed, everyone watching us. I want him to stop, I want to cry and shout at him but I have lost my voice.

He puts me up against a wall and points his gun at me, one of his eyes is screwed half-shut and looks cold and inscrutable.

Don’t let me fall, I think, if I fall I’ll drop in the mud.

But my feet are already slipping…

I am standing in the passage and there are my parents, in their pyjamas, giving me surprised and anxious looks.

‘What are you doing out here, why aren’t you asleep? Do you have to go to the lavatory? Jeroen, can you hear us?’

My mother leads me back to my bed. I let her tuck me in, her hands soft and familiar.

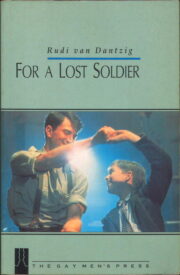

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.