There is frenzied dancing on an open piece of ground ringed by curious spectators. Most of the men are soldiers.

They hold the women and girls tight, then suddenly thrust them away fast, turn round, catch them on one arm and bend over them with practised ease.

The girls move about on agile, eager legs, turning flashily in time with the music and moulding themselves compliantly to the masterful bodies of their partners.

The few older residents who are dancing do so sedately, moving around carefully with dainty, measured steps, smiling about them politely.

‘Swing’s great, hey?’ Jan is leaning over my shoulder, his mouth close to my ear. ‘See how tight a grip they’ve got on those bits of skirt?’

His body moves in time with the music, and he hums along with delight.

We look at the couples clamped together, the quick bare legs under the short skirts, the firm grip of the soldiers’ arms, the heavy boots moving effortlessly like black, hot-blooded beasts. The heat given off by the dancers transmits itself to us, rousing us.

‘Christ, take a look at that, will you? That sort of thing oughtn’t to be allowed. Look, quick!’ I feel a push and am propelled forward. ‘See her? You keep your eye on her, it won’t be long before she’s walking around with a big belly.’

I admire them, I think they’re exciting; I want to go on looking at them for a long time, the way the two of them dance, the way he puts his arm around her and looks at her.

‘Come on,’ says Jan, ‘let’s go and have a smoke, I know somebody with a packet of Players.’

The soldier spins around like greased lightning, kicking his heels so high that they tap his bottom. He presses the girl hard up against him, his hands on her buttocks as she hangs meekly on to him. They whirl about between the other dancers, disappearing from view and turning up suddenly somewhere else. Whenever he finds enough space the soldier throws the girl up in the air, swings her between his legs as she comes down, sleekly rotates his quick hips and then takes a few long steps, one of his legs thrust out between hers.

In a corner of the playground some boys are sitting on their haunches against the fence, and when Jan joins them I squat down as well. They are smoking with self-important expressions and an appearance of doubtful enjoyment. When the military band strikes up a new tune they snigger and sing along softly so that the bystanders cannot hear them:

‘No can do, noo can do,

My momma and my poppa sez

Nookie do…’

They fall about laughing and one of the boys holds the burning cigarette high up between his legs. I look sideways at Jan. Don’t you start laughing now, I plead with him silently, don’t leave me in the lurch, please don’t laugh.

He gives me a broad grin and holds out the cigarette to irye with a friendly gesture. I grin back weakly.

Slowly I climb up our dark stairs. Players, nookie do, the shocking dancing, what a strange world these soldiers live in. None of it has any connection with Walt, even though he held me between his bare legs and pushed his thing into my mouth.

Above me a door is being opened and my mother, who has heard me coming, calls out, ‘You don’t have to walk up in the dark any longer, the electricity’s on again!’

With a click the little light on the stairs comes on.

‘Happy birthday to you,

Happy birthday to you.’

My mother is singing, and at the word ‘you’ she points Bobbie’s little arm in my direction.

A small present is lying beside my plate, wrapped in thick brown paper. When I open it, I find four exercise books, a pencil sharpener and a small rubber in two colours.

‘The black bit is for rubbing out ink,’ my father explains, ‘the red side is for pencil.’

‘We bought you the exercise books for school, make sure you keep them away from Bobbie. Do you like them?’

I nod. I feel no excitement at all about the present, only vague disappointment and indifference.

The rubber has already disappeared into my brother’s mouth. He is chewing on it and dribbling long threads on to the tray of his high-chair.

‘Tut, tut, tut,’ says my mother, ‘you little piggy, that isn’t a toy for little boys like you. Any moment now, he’ll swallow it.’ She puts the small wet object back on the exercise books. ‘That’s your big brother’s, he’s growing into a smart young man.’

‘Twelve years old today, your first birthday for five years without a war going on! That’s just about the best present of all, isn’t it? Everything’s going to change for the better now.’

My father gives me a serious look. ‘You’re going to have a lovely time from now on, son.’

The sun is slanting into the room and falls across one end of the check tablecloth. I catch the light on the blade of my knife and bounce it back on to the wall. A speck of light jumps across the wallpaper with every movement I make.

‘Twelve is quite an age, you’ll have to do your very best at school now that you’re a big boy.’

I bend the little rubber between my fingers until the ends touch. Why do I have to get bigger? I’d rather stay as I am, if I change Walt won’t recognise me.

‘Ask some friends up to play this afternoon, why don’t you,’ my mother says, ‘I’ll get them something nice to eat.’

The rubber snaps at the join of the two colours. Before they can see anything I hide the two halves in my pocket.

I continue my expeditions. One day I walk through Haarlemmerweg to Central Station, the next day over the Weteringschans to Plantage Middenlaan, and the morning after that across the sands to the Ring Dyke. But I break off that last expedition quickly because everywhere I go in that long overgrown stretch of land with its weeds and tall grasses I come across people lying in the hollows along the dyke, alone or in pairs. There is an inevitable exchange of silent looks, or signs of a rapid change of position, so that, despite the rumours that there is an army camp somewhere along the dyke, I turn around and return to the busy streets.

The morning I pick up the piece of paper with the letters V.B.S. – C.B. on it, I hear my father, who is listening to the radio, suddenly curse softly ‘God help us all…’ I try to catch the announcer’s words. He is saying something about ‘Japan’, ‘American air force’, ‘an unknown number of victims’, but the meaning of it all escapes me. My father is listening attentively. I ask him no questions.

The expeditions into town have begun to exhaust me and I continue them without any real faith. My conviction that I shall find Walt again has worn thin; sometimes I have to jolt my memory to remind myself why I am in the part of town where I happen to be and for what purpose. I walk, I trudge along, I sit on benches, stare at passers-by, look into shops, long to be back home, anything so as not to think about him.

On the Ceintuurbaan I recognise the cinema I went to with my mother a few years back, when the war was still going on.

Dearest children in this hall, Let us sing then, one and all: Tom Puss and Ollie B. Bommel!

I had sung along obediently but my illusions had been shattered. Ollie B. Bommel, I told my mother, was much too thin, his brown suit hanging like a loose skin about his body. And Tom Puss (Tom Puss, Tom Puss, what a darling you are’ – but by then I had stopped singing along) had turned out to be a little creature with a woman’s voice prancing coquettishly about the stage.

I stop on a bridge to watch the fully-laden boats moving towards me down the broad channel and then disappearing beneath me. A boy comes and stands near me and spits into the water. He keeps edging closer to me. When he is right next to me, he says, ‘Want to come and get something to drink with me? There’s nothing much doing round here.’

I am afraid to say no, follow him towards an ice-cream parlour on the other side of the bridge and answer his questions: don’t I have to go to school yet, do I live around here and when do I have to be back home? He is wearing threadbare gym shoes and his hair has been clipped like a soldier’s, short and bristly.

I am flattered that an older boy is bothering with me and paying me so much attention, but the sound of his voice and also the way he keeps scratching the back of his neck as he asks me questions put me off. When I realise that his arm is touching my shoulder I quickly move a bit further away from him.

‘What do you want, an ice-cream or something to drink?’ he asks when we are inside the small ice-cream parlour. ‘I can ask if they have lemonade.’ He looks at my legs which I have stuck awkwardly under my chair, smiles at me conspiratorially and whistles softly through his teeth.

When he is standing at the counter I race out of the shop and run on to the next bridge. A tram labouring up the incline just misses me, clusters of people hanging from the footboards. When the second carriage draws level I run beside it and grab a held-out hand. I balance on the extreme edge of the footboard and clutch the handle, dizzy with fear; I am going to fall, I’ll be lying in the street, Mummy won’t know where I am… My hands hurt and I am afraid they will slip off. Houses pass by at breakneck speed, the man next to me leans more and more heavily against me, but after a little while it begins to get exciting, there is a friendly atmosphere among that tangle of bodies, people joke with each other, shove up obligingly and call out to passers-by. When I finally dare to look out sideways I can see where we are: Kinkerstraat, that was quick, and it didn’t cost anything either!

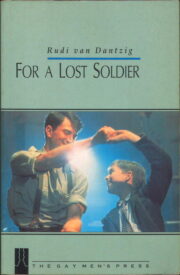

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.