I stiffen when I suddenly realise what has happened: the wet shirt with the small pocket is hanging from two pegs among the other washing. The photograph.

When my mother has gone into the kitchen, I slip my fingers quickly into the opening in the shirt. How could I have forgotten! I touch a small, crumpled wad but keep on fumbling wildly and incredulously. Then I pick it up between my fingers and unfold it, a matted, mangled bit of paper.

‘What have you done?’ My voice sounds distorted and shrill. ‘There was a photograph in my shirt. Couldn’t you have waited?’ I almost scream the words at her.

My eyes fill with tears. Back in my room I fling myself onto the bed and squeeze the scrap of paper desperately between my fingers.

‘I don’t know what’s got into him.’ From the sound of her voice I can tell that my mother is crying as well.

My father soothes her, their voices disappearing towards the living-room. When the door shuts there is a deathly silence.

‘If you don’t go down to play today I’m just going to push you out of the door,’ she says next day as she sets a cup of warm milk before me on the table. ‘Don’t you turn into a stay-at-home, you hear? Children are meant to play outside.’

She talks gently and I can see that she is smiling. And yet I hear the anxious undertone in her voice and her whole attitude suggesting that she is feeling her way with me.

After looking out of the window to make sure none of the boys are outside I decide to go downstairs. I run towards the canal and then, as if doing something that is not allowed and that mustn’t be seen by anyone, I turn down another street towards the White School. It feels as if everyone is watching me, that they are wondering what I am up to, why I am there and what I am going to do.

I walk past the school fence alongside the deserted playground. There is a broken-up-for-the-holidays air about the place: thick clumps of grass and weeds are sprouting here and there between the paving stones, and the narrow flower-beds under the windows look neglected and overgrown. Most of the classrooms appear empty, the plants and drawings on the windowsills gone, all the colour and gaiety vanished. From an open window comes the loud voice of someone talking over the radio in a foreign language. I stop and fumble cautiously with one of my socks, trying to look inside unnoticed. One classroom has been turned into a store, piled high with crates and bags, and my own classroom has been converted into a kitchen or dining hall, the windowsill lined with cooking pots and metal pans. In the gym there are long rows of narrow beds on crossed legs; rucksacks, boots and helmets stand underneath them in orderly array. The recognition of all these things throws me into total confusion. I want to walk away but I remain where I am with my fingers clutching the wire netting of the fence, listening to the sounds echoing across the square, the metal clink of boots, a car starting up, the laughter sounding through an empty classroom.

It seems that the whole street is staring at my back, as if my clothes bear a message writ large: this boy is in love with a soldier. ‘The slimy creep, that dirty sneak,’ I can hear them call after me in my imagination. A soldier crossing the playground looks at me and takes a few steps in my direction. He rummages about in his pocket, whistles, and then flings something at me as to a dog: a colourful, hard little object which lands on the ground by my feet. I stiffen and walk away.

Back in our street a group of boys is sitting on the pavement. Appie is there, and Wim and Tonnie. I go and stand beside them, leaning against the wall and listening to what they are saying. Wim turns round to look at me. ‘Hey, are you back too, then? Did those peasants stuff you full of food?’ It doesn’t sound unfriendly, at worst mocking, but I feel hostility and a great gulf. The boys laugh. Should I sit down with them, behave as if everything is back to normal, as if I have never been away and nothing has happened to me?

A squad of soldiers comes marching down the street and the boys run over to them, leaping around them, shouting and drawing attention to themselves, then fawning on them sweet as sugar.

I am shocked by the liberties they take, grabbing hold of the soldiers’ arms and running along with them like that.

‘Hello, boy. How are you? Cigarette, cigarette?’ they pester, and the soldiers smile back at them, seeing nothing bad or rude in that sort of behaviour.

I am ashamed and jealous at the same time. I should love to walk along like that and be so free and easy with those soldiers, laughing up at them and holding on to their clothes. Even with Walt I shouldn’t have dared to act like that, it would never even have occurred to me.

Tonnie walks slowly back to me and nonchalantly brings a small box out of his pocket. There is a picture on it of a bearded man wearing a sailor’s cap under which you can see sandy hair.

‘Players,’ he says, opening the packet. I see two smooth round cigarettes lying at an angle inside the silver wrapping. ‘Want to swop? What have you got?’

When he realises that I have nothing he looks surprised and then disdainful. He calls the others over.

I must try to get away, I am wasting time when I could be searching, watching the classrooms, keeping an eye on the cars. When the boys get into a huddle in a doorway, their heads conspiratorially close together, I disappear around the corner and run to the other side of the school.

There they are, a whole lot of soldiers sitting on the running-board of a car, on the paving stones, some in a school window with their legs dangling out; they are like a group of animals basking in the sun on a rock. They talk, polish their gear, laugh, laze about; one of them even has a needle and thread and is mending something.

Brown arms, pliant necks under short-cropped hair, nonchalantly outspread legs, a young boy squatting on his heels who confuses me so much that I dare not look in his direction: the wad of a photograph, in my cupboard, the face that has been lost. I feel the skin of my cheeks tighten and my eyes start to burn.

A small open car comes driving across the playground with three girls sitting in it, their arms wound provocatively around each other’s waists, bursting again and again into noisy giggles, doubling-up with laughter then collapsing against one another. The soldier at the wheel has huge shiny arms and deep black eyes that, half-amused, half-bored, take stock of the other soldiers who come running up to the car, shouting incomprehensibly. The girls shriek, allowing themselves to be lifted out of the car. A moment later, they go inside the school, tittering and holding tightly on to each other, followed slowly by the soldier with the muscular arms. His hands are in his pockets and he has a powerful, bow-legged walk.

‘And have a guess what they’ll be doing inside?’ says one of the boys who has come to stand by the fence a short distance away from me.

‘They’ll be having it off,’ bawls another and rams his body against the railings, setting off a devastating din.

He is just a monkey in a cage, I think, the whole lot of them no better than animals the way they carry on making an exhibition of themselves. Why can’t the soldiers see that? But the soldiers are gesturing to the boys, pulling faces and giving them knowing winks.

I am cross, and jealous of everyone, of the boys, of the giggling girls and of the soldiers. Why are they looking so pleased with themselves, what are they doing inside, why is there such a strange air of excitement about the place? I don’t even think of that other thing, because that was only between me and him. The girls are probably being given rice with raisins right now, or chewing-gum.

But why should I care? I must go into town and look around some more, try to find those places I saw from the boat, where the cars were parked.

I walk as far as Admiraal de Ruyterweg and suddenly, when I see all the buildings and the streets full of people walking about, queuing outside shops or busy repairing the pavements and the tramlines, I daren’t go on. Must I really go through these crowds all by myself? What if I lose my way, or if something happens to me?

But I still have to find him, as soon as possible. Every day I fail to look for him is a day lost. He may still be here today, but tomorrow he could have gone.

I walk another block, my anxiety growing all the while, then I turn on my heels and run back home without stopping.

I thump on the front door, fly up the stairs and stand panting in the passage.

‘Was it fun playing with your old friends again?’ asks my mother. I pretend not to hear and disappear into my little room. When, cautiously, she opens the door a little while later, she gives me a worried look.

‘Nothing happened, did it? You didn’t get into a fight? If there is anything the matter, you will tell me, won’t you? Promise?’

Chapter 2

That evening there are celebrations in our street.

Loudspeakers have been tied to two lampposts, and every so often a man’s voice comes out of them, cutting right through the cheerfully blaring marching music to address the people of the neighbourhood. ‘You are all invited to join in this evening’s festivities and enter the competitions for the attractive prizes you will see specially displayed. The celebrations will be graced with the presence of a neighbourhood personality well known to one and all, whose name I am not yet allowed to divulge but who will be treating us to her glorious talent.’ For a moment the marching music drowns out the announcement, then, ‘By way of a bonus I am pleased to be able to tell you that Mijnheer Veringa has kindly agreed to open the festivities with a special address.’

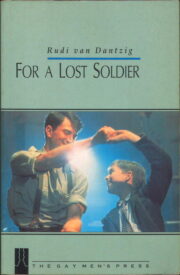

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.