‘What’s that?’ she says and takes hold of my arm. The wound festered and there is still a scab.

‘Nothing. Hurt myself playing.’

After that I am allowed to sit out on the balcony for a little while. It is dark but warm and we drink ersatz tea. I can hear the tinkle of cups from the neighbours’, and voices through the open windows, peaceful, unimportant sounds that make me feel sleepy. Down in the street Jan is already playing with the boys as if he had never been away.

I move back a bit and sit where no one can see me from downstairs. The street resounds with shouting and singing.

Inside my mother is unpacking the panniers.

‘Bacon,’ I hear her say, ‘real bacon. And rye-bread. And that’s sheep’s cheese, just smell it. They made that themselves.’

I go back inside quietly.

‘Poor dear, he’s worn out,’ she says compassionately. ‘Come, I’ll make up your bed, it’s been quite a day for you, hasn’t it?’

My father lets the bed down. I give him a kiss. Go now, I think, leave me by myself. But he lingers on.

My little room looks bare, lifeless. Everything has been tidied away carefully and is in its proper place.

My mother pulls the blankets up to my chin and sits down on the bed. ‘It’s nice at home with your own mummy and daddy, isn’t it,’ she says enthusiastically. I seize hold of her arm. Who can help me, what will happen to me? ‘Tomorrow we’ll go up to town together, there are celebrations all over the place,’ she says, ‘in our street, as well. How wonderful that you’re back in time to join in. There isn’t such a lot happening in Friesland, is there?’

She opens the window a crack and draws the curtains.

‘Off you go to sleep now. You’re sure to have some wonderful dreams.’

I listen until the door has been pulled to. Then I bury my head deep under the blankets.

FREEDOM AND JOY

Chapter 1

There are sounds all around me: the clumping of footsteps on the floor above us, the rattle of dustbin lids on the verandas, voices in the street, a song echoing over the gardens across the road. Is it late? I close my eyes again and try to shut out the day. My bed feels good now that I am awake, wonderfully soft and yielding, and I let myself sink into it as into an embrace. During the night I woke up with the anxious feeling that I was sliding into a substance from which, try though I might, I could no longer extricate myself. I had finally struggled upright and had sat on the metal edge of the folding bed, panting and worn out. The little room looked ghostly and unreal: walls that seemed too far away, dawn glimmering in the wrong corner, unfamiliar sounds. Confused, I had slipped back under the blankets.

At breakfast, in our room that seems spacious and sunny and where there are only three instead of nine sitting at table, I feel like a guest who has merely spent the night and is about to set off again.

I can’t get used to the new way the furniture is arranged.

‘Did you sleep well?’ my father asks. I can hear the probing tone in his voice.

‘Yes, thanks. But the bed is so soft, I’m going to have to get used to it again. The cupboard-bed in Friesland was made of wood.’

‘You shouted out in the night, do you know that? You don’t have to be afraid any longer, everything is over, you’re back at home now. Life is back to normal again.’ My mother lays a hand softly and protectively on mine. My forehead begins to tingle, a feeling of anxiety comes over me, but I daren’t draw my hand back. Nobody may touch me, it’s not allowed. She puts a big square biscuit on my plate.

‘Would you like some of this? Don’t pull such a face, it’s a ship’s biscuit, delicious! From the Canadians.’

I smell it and push the thing away. ‘Isn’t there any ordinary bread?’

She goes to the kitchen and cuts a slice of the Frisian rye-bread. ‘I thought you might want to eat something else for a change.’ She looks disappointed.

In the little side-room my brother is making spluttering noises in his cot. My mother gets up and takes him in her arms. She kisses him, holds him up in the air at arm’s length and then pats his wet nappy fondly.

At the table she feeds him bits of ship’s biscuit dipped in tea and his little chute-like mouth becomes covered in brown blobs. He waves his arms about wildly and uncontrollably, knocking the spoon out of her hand so that the tablecloth, too, becomes covered with mess.

‘Da-da-da-da,’ he sings, happy, ignoring me completely, as if I am not there, as if everything is the same as always. ‘Jeroen,’ my mother prompts him. ‘Toon-toon.’ ‘Da-da-da.’

‘You’ll have to repeat the sixth year,’ my father says. ‘We’ll just have to write off this last year, they can’t have taught you all that much in Friesland.’

Who says so? How do you know? Aren’t the Frisians good enough for you all of a sudden?

‘We’ve found you a 6A class where they prepare pupils for high school. It’s quite a long way from here, in town, but they’re sure to bring your maths up to scratch.’

I go back into my room and sit down on the unmade bed. My books are stacked in a neat little row, my toys on a shelf in the cupboard, the drawing-book, the pencils, my sponge-bag, everything is there, all my things. When I was in Laaxum I missed them, but now I don’t even touch them. I am listless and anxious and don’t feel like moving.

My little brother is crying, whining and whimpering. I can hear my mother talking in a subdued voice out in the passage, as if I were still asleep.

‘I’ll take him outside for a bit of a walk, the weather’s lovely. Then we can leave Jeroen here a while longer, he still has to get his bearings back.’

For a long time I sit there motionless. What shall I do? Quietly I open the door. My father is standing in the kitchen.

‘Well, did you give your room the once-over? Is everything just as it should be?’ There is a teasing undertone to the way he says it. He goes out onto the veranda and hangs a row of nappies on the line. When I go and stand beside him and look over the railing, he kisses my hair. ‘Great to have you back,’ he says, ‘we missed you.’

I look at the green gardens, the canal and the cultivated fields beyond. There is a barn and vegetables planted in long straight rows. My mother is sitting on a bench by the water, a pram next to her, and she waves when my father calls her name. She looks pretty and happy. ‘Come,’ she beckons to me.

‘Go and get some fresh air, sitting about indoors won’t do you any good. Soon you’ll be stuck inside school all day again.’

We walk through the house and my father shows me everything. ‘Look, we’re back on the gas and the electricity. The radio is going again too, just listen. If you turn this little knob you get music.’

‘Perhaps I’ll just go into town this afternoon,’ I say, ‘to have a look what’s going on.’

‘You go and have a good look round, there’s a lot to see, celebrations and exhibitions everywhere. I’ll come later in the week and we’ll look at things together.’

He watches me as I go down the stairs and turn round once more, as if I am asking for help. Downstairs I stop inside the main door for a while, summoning up the courage to open it and venture out into the street. Then I run around the corner and sit down on the bench beside my mother. She is rocking my brother’s pram to and fro, first forwards, then backwards, making me sleepy just watching.

‘Go and find the other children, they’ll be glad to have you back. You must have a lot to tell them about where you’ve been.’ But I stay sitting next to her, clutching her arm as she rocks the pram. When a soft drone of engines can be heard she says that it’s sure to be the Canadians. ‘They’re quartered in your school, but I don’t know for how much longer. Go and have a look. Sometimes you can see a whole procession of cars passing by.’

At the end of the street, by the White School, I watch two cars being driven out of the playground and disappearing around the corner. Men in the familiar green uniform are walking about in front of the wide-open doors that lead into the gymnasium.

So, they’re here, right next to our house…

Suddenly I run back home and sneak up the stairs, feeling almost caught out, ashamed and agitated.

‘No,’ I tell my father when he looks surprised to see me back so soon. ‘I’m not going to go out today, I’d rather stay at home, I don’t want to go out on the street.’ I walk onto the balcony and look at the school, at the open gym and the soldiers’ comings and goings. I feel sluggish and washed out. Should I go and look to see if he is there? And if he is, what then?

I go into my little room to sit down, and notice that some of the pages from my books have been ripped out while others have been covered with big scratches. The work of my little brother, that’s for sure. Restlessly I leaf through the books, read a line here and there, look at the pictures, then push the books to one side again.

My father puts a small plate with neatly cut sandwiches and a peeled and quartered apple down next to me.

The terror inside me wells up, takes possession of me slowly and paralyses me. I don’t ever want to move again, ever go down in the street again. I don’t ever want to see anybody again.

I put the plate down on the windowsill: I don’t like the food here either. Nothing in Amsterdam tastes of anything.

In the afternoon my mother takes down the nappies while I sit on the kitchen doorstep and watch her quick hands collect the washing. She hangs other pieces of clothing on the line: my shorts, underwear, my towel, the socks knitted by Mem.

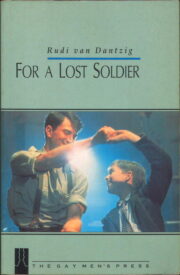

"For a Lost Soldier" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "For a Lost Soldier". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "For a Lost Soldier" друзьям в соцсетях.