Thursday 7 August

Maria and Julia were given a holiday so that they could get to know Fanny better, but they soon tired of her, remarking disdainfully, ‘She has but two sashes, and she has never learnt French.’

I saw her standing in the middle of the hall this afternoon looking lost and I asked her what she was doing. She blushed and clasped her hands and said that Aunt Norris had sent her to fetch her shawl from the morning-room, but that she did not know where it was. I undertook to show her the way, and said kindly, ‘What a little thing you are,’ but this seemed to make her more anxious so I made no further comments on her size. Once she had found the shawl I watched her until she disappeared safely into the drawing-room.

‘She looks at me as though I am a monster,’ said Tom when I mentioned it to him later. ‘I found her in the drawing-room this morning and asked her how she did. She did not reply, so I told her not to be shy, and she blushed to the roots of her hair.’

He suggested we go fishing, and we took our rods down to the river, where we caught several fish which were served up at dinner with a butter sauce.

Friday 8 August

Aunt Norris is very pleased with her protégée and after dinner, when Fanny had left the drawing-room, Mama and Papa remarked that Fanny seemed a helpful child who was sensible of her good fortune. Maria and Julia pulled faces at each other at the mention of Fanny, but said nothing more than that she seemed very small and always had the sniffles. I could not blame them, for she does always seem to be ill, poor child.

Wednesday 13 August

Tom and I rode out early, basking in the warmth. The dew was on the grass and all nature seemed to be waiting expectantly for the day to begin. Tom laughed when I said as much, and said I should become a poet.

We made a hearty breakfast and then he rode into town whilst I returned to my room. As I did so, I heard a strange sound, and I realized that it was sobbing. I followed it, to find our little newcomer sitting crying on the attic stairs.

‘What can be the matter?’ I asked her, sitting down next to her and wondering how to comfort her, for she looked very woebegone.

She turned a fiery red at being found in such a condition, but I soothed her and begged her to tell me what was wrong.

‘Are you ill?’ I asked her, for to tell the truth, she did not look well. She shook her head.

‘Have you quarreled with Maria or Julia?’ I asked, wondering if they had upset her.

‘No, no not at all,’ she whispered.

‘Is there anything I can get you to comfort you?’

She shook her head again. I thought for a moment and then asked, ‘If you were crying at home, what would you do to make yourself feel better?’

At the mention of home, her tears broke out anew, and it was easy to see where her sorrow lay.

‘You are sorry to leave your mama, my dear little Fanny, which shows you to be a very good girl,’ I said kindly. ‘But you must remember that you are with relations and friends, who all love you, and wish to make you happy. Let us walk out in the park and you shall tell me all about your brothers and sisters.’

I took her by the hand and led her outside, for the morning was such as to cheer anyone. The sky was blue and soft breezes were blowing across the meadows. I heard about Susan, Tom, Sam and the new baby, but most of all I heard about William.

‘How old is William?’ I asked her.

‘Eleven,’ she told me, with the awe that only a ten-year-old can muster for such an advanced age.

It was with William she played, William who was her confidant, William who interceded with her mother on her behalf when needed, for he was clearly a favorite with Mrs. Price.

‘William did not like I should come away; he said he should miss me very much indeed,’ she said with a sob.

I handed her my handkerchief and persuaded her to take it, for her own was wet through.

‘Never fear, he will write to you, I dare say,’ I reassured her.

‘Yes, he promised he would, but he told me I must write first.’

I soon discovered that this was the cause of her tears, for she had been longing to write to him since her arrival but she had no paper.

I took her into the breakfast-room so that she could send a letter at once, but as soon as I had furnished her with everything necessary, a fresh worry raised its head and she was afraid it might not go to the post.

‘Depend upon me it shall : it shall go with the other letters, ’ I told her, ‘and, as your uncle will frank it, it will cost William nothing.’

The idea of my father franking it frightened her, as though such an august personage should not be expected to help her, but I reassured her and at last she was easy.

‘Now, let us begin,’ I said.

I ruled the lines for her and then sat by her whilst she wrote her letter. I believe that no brother can have ever received a better one, for although it was not always rightly spelt, it was written with great feeling.

When she had finished, I added my best wishes to her letter and enclosed half a guinea under the seal for her brother. The look of gratitude she turned on me was enough to reward me ten times over for my small trouble, and I began to feel that she was a very sweet little thing, with an affectionate heart. I took some trouble to talk to her and discovered that she had a strong desire of doing right, as well as an awe of Maria and Julia.

‘You must not be afraid of them,’ I said to her. ‘They are only further ahead than you because they have had a governess, whilst you have not, but life is not all French and geography, you know. It is fun and games as well. You must remember to play with my sisters, and to enjoy yourself. We all of us want you to be happy, and you will oblige us greatly if you can manage it. will you try?’

She nodded timidly.

‘Good.’ I saw my sisters on the lawn. ‘Look! They are out in the garden. The sun is shining, it is a beautiful day. You should go out and join them.’

She dried the last of her tears, looked at me for reassurance, then slipped off her chair and went over to the door. She turned back, and when she saw that I was watching her kindly, she smiled and waved, then ran outside. I saw her emerge on to the lawn and approach Maria and Julia. Maria looked about to rebuff her but when she saw me watching she held out her hand to Fanny. Fanny went to her shyly, and before long the three of them were playing together. I thought she might like some books to read when she returned to her room, so I chose some from the library for her, and then I walked over to John Saddlers to see about some new harness for Oberon.

Friday 15 August

Tom and I went into town this morning. I had some commissions to undertake for Mama and Aunt Norris, and some books to buy for myself, whilst Tom wanted to look at another horse.

‘Not to persuade Papa to buy, just to look at,’ he told me.

We met at the inn for luncheon and he refused to tell me about his parcels, but when we returned home, all was made clear. After dinner, he gave a new shawl each to Maria, Julia and Fanny, with all the liberality of a future baronet. Maria wished hers had been blue, and Julia coveted Maria’s, which, however much she said she disliked it, she would not exchange, whilst Fanny was too overcome to speak. When she could at last thank him, she stumbled over her words and then went bright red, before escaping to the nursery with her treasure.

‘She is a funny little thing,’ said Tom, as the door closed behind her.

‘She seems a pleasant child,’ said Mama, stroking Pug behind the ears and adding, ‘does she not, Pug?’

‘She is prodigiously stupid,’ said Maria complacently. ‘Only think, she cannot put the map of Europe together. Did you ever hear anything so stupid?’

Aunt Norris shook her head.

‘My dear, it is very bad, but you must not expect everybody to be as forward and quick at learning as yourself.’

‘Hah!’ said Tom, but Maria ignored him.

‘I am sure I should be ashamed of myself to know so little, ’ said Julia. ‘I cannot remember the time when I did not know a great deal that she has not the least notion of yet. How long ago it is, Aunt, since we used to repeat the chronological order of the kings of England, with the dates of their accession, and most of the principal events of their reigns!’

‘Very true indeed, my dears, but you are blessed with wonderful memories, and your poor cousin has probably none at all.’

‘But I must tell you another thing of Fanny, so odd and so stupid,’ said Maria. ‘Do you know, she says she does not want to learn either music or drawing.’

‘To be sure, my dear, that is very stupid indeed, and shows a great want of genius and emulation,’ returned Aunt Norris. ‘But, all things considered, I do not know whether it is not as well that it should be so, for, though you know (owing to me) your Papa and Mama are so good as to bring her up with you, it is not at all necessary that she should be as accomplished as you are. On the contrary, it is much more desirable that there should be a difference.’

‘I believe Fanny will like music and drawing well enough once she knows more about them,’ I said, unwilling to have Maria and Julia encouraged to slight her. ‘She has not had a chance to study them so far, that is all, and so she does not yet understand their worth. Do you not think so?’ I asked Mama.

‘You must ask your father, Edmund. He will know. See what Sir Thomas thinks,’ returned Mama placidly.

I was disheartened, as I had hoped she would join her voice to mine, but at least my words curbed my sisters’ contempt enough to make them conceal it from Fanny. I would not like to find her in tears again, for she is so small and thin she looks as though she could hardly stand it. Tom was an unexpected ally, for he said he saw no harm in her and he was sure she would grow up to be perfectly charming, then teased Maria and Julia by saying that they should emulate Fanny’s gratitude, or he would not bring them any more presents.

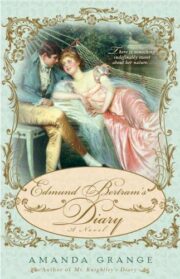

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.