‘I would never have talked to you about Mary had I known,’ I said. I thought of the way I had gone to Fanny’s room, asking her to help me with the play, expecting her to prompt Mary and me as we spoke words of love to one another under the guise of drama.

‘That was not the hardest part,’ she said.

‘No?’

‘No. The hardest part was when you urged me to marry Mr. Crawford.’

‘I shudder to think of it. I cannot believe I was so blind. You would have been trapped with a vicious, shallow man, and I would have been left to rue the day I urged my Fanny to marry him.’

‘Not if Miss Crawford had accepted you.’

‘Yes, even then, for the scales must have fallen from my eyes eventually, and then I would have bitterly repented my blindness, and bitterly repented my loss of you. But let us not speak of such things. We have been saved from disaster, and now we can look ahead. We will be very happy, will we not?’

‘We will,’ she said.

‘You have been right about everything else, Fanny, and I know you will be right about this as well.’

We were disturbed by a sound from indoors, and Fanny said, ‘We had better go in to supper.’

‘If we must. I would rather stay out here talking to you, but duty must be done.’

We sat together at supper and, Fanny pleading fatigue afterwards and partners being plentiful, I spent the rest of the evening sitting by her side.

Friday 11 August

As soon as I had broken my fast I went into the drawing-room, hoping to find my father and ask him if I could have a private word with him, but the only person there was Aunt Norris.

‘I saw you,’ she said to me accusingly, as I was about to go. ‘With her, that interloper, last night. We have nursed a viper in our bosom. When I think what we have done for that girl, taking her in and raising her here at our expense, and this is how she repays us: first, by ruining Maria because of her own stubborn stupidity, and then by artful y throwing herself at you — hoping, no doubt, that your brother would die, and she would find herself the mistress of Mansfield Park.’

I did not even deign to reply, but my aunt had not finished.

‘Sir Thomas saw how it would be, even before she came here. He knew it would be difficult to preserve the difference in rank between Fanny and his daughters, but I told him nothing could be easier than making sure the distinction was preserved. And I am sure I have played my part, not allowing her to sink into idleness but giving her errands to run, making sure she did not expect to have the carriage ordered for her, seeing to it that her clothes did not match those of dear Maria and Julia, and ensuring she never had a fire in her room. I reminded her of how fortunate she was, to be taken in by her wealthy relatives—’

‘That is certainly true,’ I said, as she paused for breath. ‘You never let her forget it.’

She was still ranting when I left the room.

I found my father in his study, and felt a momentary qualm as he told me he was at my disposal. Maria and Julia had disappointed him, and I was afraid I was about to do the same, for I knew there had been some truth in my aunt’s words, and that he hoped I would marry a wealthier woman than Fanny.

But when I told him that I loved Fanny, and that I would like his permission to marry her, his response was everything I could have wished for.

‘To think I once feared this outcome!’ he said. ‘My feelings are now so very different that I give you my permission willingly, even happily. That is, if Fanny accepts you.’

‘I have already asked her and yes, she does.’

‘Then I will also add my blessing. I used to want something very different for you, but I am sick of ambitious and mercenary connections, and I am glad you never wanted them. I have been watching the two of you with pleasure for some weeks now, and hoping you would find your natural consolation in each other for all that has passed. Events of recent months have made me prize the sterling good of principle and temper, and there is no one with better principles or a better temper than Fanny.’

I found Fanny in the garden and told her of my father’s consent. She smiled happily, and as we walked together down the avenue, under the shade of the arching trees, with the warm air playing about us, I said, ‘I have been thinking about Thornton Lacey. I think we will enlarge the garden, then you can grow your geraniums there.’

‘Oh, yes, Edmund, I would like that.’

We walked and talked as the sun climbed in the sky, and had not exhausted our conversation by dinner-time.

After dinner, I told Mama the happy news. There was a moment of alarm when she first heard it, for she said, ‘What! Take Fanny from me? Oh, no, I cannot do without Fanny.’

‘But she must go with Edmund to Thornton Lacey when they are married,’ said my father.

‘But what will I do without her?’ asked Mama.

‘You must ask Susan to stay,’ said my father.

Susan’s face was glowing. She, too, had found it hard to live at Portsmouth, where there was no order or discipline, and delighted in being at Mansfield Park.

‘Oh, yes, Sir Thomas, you are such a comfort to me, you always know what to do,’ said Mama.

‘Susan, my dear, you will stay with us, will you not? For I do not know what I would do without you.’

Susan said she would be delighted to stay, and by her attentions to Mama after dinner, made herself so indispensable that it seemed as though she had always been with us.

DECEMBER

Sunday 31 December

How much has changed since last year’s end. Maria has left her husband and is now living in retirement with Aunt Norris, whilst Rushworth is suing her for divorce; Julia has married, and after an unpromising start, seems to be happy with Yates; Tom has been seriously ill and recovered, and no longer lives only for pleasure but is taking an interest in the estate; Dr Grant has died, so that I have acquired the Mansfield living; and Fanny and I are married. We are the same, Fanny and I. As I watch her tending the flowers in her garden, or comforting one of our parishioners, or dancing at a ball, or sitting opposite me at dinner, I bless the day she came to Mansfield Park.

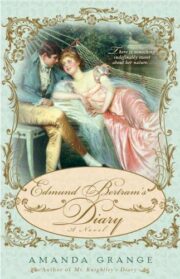

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.