Monday 18 August

We heard this morning that the rector of Thornton Lacey had died. Papa called me into his study and gave me the news, then told me that he intended to give the living to Mr. Arnold, who will hold it for me until I am of an age to take it myself, if I so wish. He asked me if I had given any more thought to my future, and I confessed that I had not.

‘No matter. The living of Thornton Lacey will be held for you anyway and you may take it or not as you please when you are older. It is not the best living in my gift, for that, of course, is Mansfield, but in the fullness of time, that, too, will belong to you. Now, tell me of your studies, and of what you like to do.’

He listened as I told him about my progress at school, and asked me several judicious questions, and then I was free to go.

I went out to the stables and found Tom. Before long, we were riding out towards the woods.

‘So Papa was asking you about your choice of profession? I am glad I do not have to make any similar decisions, for I would have no idea what to do if I could not run riot with my friends. I wish Jarvey were here, though perhaps it is better he is not, for he is always wanting to be doing something, and today it is too hot to do anything more than ride in the shade and dream of pretty girls.’

We went home with a hearty appetite and I finished my dinner with three slices of apple tart. Julia called me greedy, but Aunt Norris said that Tom and I were growing boys and that she liked to see a healthy appetite.

Thursday 21 August

I was walking through the park this afternoon when I saw little Fanny returning from the rectory with a large basket. It was far too heavy for a girl of her size and strength, for she was leaning over to one side in an effort to balance the weight, and she was perspiring profusely. Her breathing was shallow as I approached her, and I was concerned for her health.

‘Here,’ I said, taking her basket, ‘you must let me carry that. Whatever possessed you to go out in such heat, without a hat, and to carry such a heavy load?’

‘Mrs. Norris wanted her work basket and had left it at the rectory,’ she said timidly.

‘You should not have offered to fetch it for her. You are not strong enough,’ I said. She looked awkward, and I guessed that she had not offered, but that my aunt had sent her.

‘Let us sit awhile,’ I said. ‘It is cool under the trees. You may catch your breath, and then we will return to the house together.’

I spread out my coat for her, and bade her sit down. I was about to ask her about William when she surprised me by reciting:

The poplars are felled, farewell to the shade

And the whispering sound of the cool colonnade.

‘You have read the Cowper I gave you,’ I said, much struck, for, although I had defended her at the time, I had been guilty of believing my sisters when they said that she was stupid.

‘Yes,’ she whispered. ‘I read it every night.’

‘You seem to be a very devoted student, little Fanny,’ I said with a smile. She gave a tentative smile, too, but this time it was with pleasure. I talked to her about the things she had read, and found an intelligent mind beneath her timidity. When she was ready to go on I walked slowly beside her, and took her into the library.

‘Aunt Norris...’ she said.

‘A few minutes more will not make any difference.’

I talked to her about what she liked to read and helped her to choose some books, then I accompanied her into the drawing-room, so that I could turn aside the worst of my aunt’s ill humor. I appealed to my mother, who said that Fanny must not be sent out without a hat in such heat again, and received a look of grateful thanks from my little friend. Tom was lounging on the sofa, and he suggested we go and see Damson’s new puppies.

‘Though you do not need one,’ he remarked, as we left the drawing-room, ‘for I am sure it will not follow you around as adoringly as Fanny, nor come so readily when you call.’

I smiled, and he teased me some more, and told me that if I decided against being a clergyman or a poet, I would make a very good governess.

Friday 29 August

The candles were brought in earlier today, and it made me realize that summer is drawing to its end. Soon it will be time to go back to school. I would rather stay here at Mansfield Park. I confided my feelings to Fanny when we walked together in the grounds, as has become our custom after breakfast, and then I was surprised I had done so. But there is something comfortable about the patter of her little feet next to mine, and something indefinably sweet about her nature that seems to invite confidences. She told me that she would rather I remained at home as well, then looked surprised at her own courage in speaking. I could not help but smile.

‘I will miss my shadow when I have gone,’ I said.

I asked her about her reading and found that she had read the books I recommended, and that she had committed a surprising amount of verse to heart. She is an apt pupil, and I think it will not be long before she ceases to draw down my sisters’ contempt for her lack of learning. I spoke to both Maria and Julia today, telling them they must be kind to her when I am away, and I have wrung a promise from them that they will protect her from the worst of Aunt Norris’s attention. My aunt is very good, but I believe she does not realize how young Fanny is, or how easily wounded. A harsh word, to Fanny, is a terrible thing. And then she is so delicate. She tires quickly and is prone to coughs and colds. I hope the shawl Tom bought her will be enough to protect against winter’s draughts.

Tom was morose when I mentioned that we would soon be back at school, but then he brightened.

‘Only one more year, Edmund,’ he said. ‘Only one more, and then I will be up at Oxford. And in two years we will be there together.’

1802 NOVEMBER

Tuesday 9 November

I wondered what Oxford would be like, and whether I would take to it, but now that I am here I find I am enjoying myself. Tom came to my rooms when I had scarcely arrived and told me he would take care of me. He hosted a dinner for me tonight and it was a convivial evening, though I was surprised to see how much he drank. At home, he takes wine in moderation, but tonight he seemed to know no limit. I held his hand back as he reached for his third bottle, asking him if he did not think he had had enough, and he laughed, and said that he would not listen to a sermon unless it was on a Sunday, and at this his friends laughed, too. I felt uncomfortable but I suppose I must grow used to some wildness now that I am no longer at school.

Wednesday 10 November

Whilst coming back from Owen’s rooms in the early hours of this morning I saw a fellow lying across the pavement. I was afraid he was ill, for I saw that he had been sick but, on approaching him, I smelt spirits and realized he was only drunk. I was about to step over him in disgust when I saw that it was Tom. His mouth was slack and his skin was pasty. His clothes were soiled, which distressed me greatly, for he has always been very particular about his dress. Many a time have I seen him berate his valet for leaving a fleck of dust on his coat or a bit of dirt on his boot, and to see him in such a state...

I tried to rouse him but it was no good, and so in the end I picked him up: no easy feat, for he is a good deal heavier than he used to be, and carried him back to his rooms.

Thursday 11 November

I called on Tom this afternoon and found him sitting on his bed with the curtains drawn, nursing his head. He said he had had a night of it, and that he could not remember how he got back to his rooms. I told him I had carried him.

‘What, so now you are a porter, little brother?’ he said, and laughed, but the laugh made his head ache and he clutched it again.

‘You should not get in such a state, Tom. What would Mama say?’ I asked, hoping that thinking of her would bring him back to his senses.

‘She would say, “Tell Sir Thomas. Sir Thomas will know what to do,” ’ he said, mimicking her. I did not like to hear him making fun of her, but I knew it would do no good to remonstrate with him. It would only make him laugh at me or, if he was in a bad mood, grow impatient.

‘Just try not to drink so much tonight,’ I said.

‘Always my conscience, eh, Edmund?’

‘You need one,’ I told him. ‘As long as you are all right, I will go. I have some work to do before dinner.’

‘You work too hard.’

‘And you do not work at all.’

‘You sound like Papa,’ he said testily.

‘You make me feel like him,’ I returned, and then I felt dissatisfied, for Tom and I have always been friends.

I tried to say something softer but he only cursed me. I saw that there was no talking to him whilst his head was so sore, and so I left him to himself and sought out Laycock instead.

Monday 15 November

Tom called on me this afternoon and my spirits sank, for he only ever comes to my room now to ask for money. He told me that he had lost heavily at cards last night and had exhausted his allowance.

‘It is a debt of honor and I must pay it,’ he said. ‘I need twenty pounds.’

I gave it to him, but I told him that it was the last time I would help him.

‘You might have money to lose, but I do not,’ I said.

‘Why worry? You are already provided for. You will have the Mansfield living when you take orders, and the living of Thornton Lacey as well. You will not be poor.’

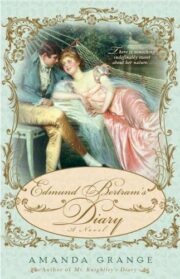

"Edmund Bertram’s Diary" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Edmund Bertram’s Diary" друзьям в соцсетях.