At last the wheels were heard coming down the drive, and while an openmouthed groom looked on, deVigne managed with some difficulty to get himself and Delsie into the carriage. From the door he directed, “Go down to the road and turn around. You’ll never manage a turn here. The minute you get to the Hall, go for the doctor at once. Take a mount, it will be faster. Close the door now, and don’t waste any time.”

He held the insentient widow on his knee, her head resting against his chest as they were driven to the road and back to the Hall. He tried to rouse her, saying softly, urgently, “Delsie. Delsie, can you hear me?” once or twice, but no response came. He cradled her in his arms, laying his cheek against the top of her head, silently cursing himself and fate for this ill-timed occurrence. Mrs. Forrester had already discovered the escape, and was anxiously pacing the hallway when deVigne carried Mrs. Grayshott in.

“I sent a boy out to tell you she’d got away,” she said, “but I didn’t know exactly where you were.”

“He’ll likely walk right into Clancy’s boys and have his head cleaved open,” he answered. “I told you to watch her, Mrs. Forrester. How did she get out?”

“It must have been by the window. Whoever would have thought she would-oh, my! She’s hurt. Is it bad?”

“I don’t know. Her color is not gone off too badly,” he replied, examining her, relieved to see in the better light that she was not so pale as the darkness had indicated. “Get some hot water and bandages-brandy. In the study,” he added, hurrying in that direction. “And a blanket. She’s cold.”

She was laid on a settee in the study. Mrs. Forrester returned with water and bandages, and was promptly sent off again for basilicum powder, and to find a boy to light the grate, while deVigne untied his makeshift bandage and examined the wound. It did not appear deep to his unpracticed eye. The skin was open, but the blood had stopped flowing. Why did she remain so long unconscious? As he began dabbing at the drying blood with a cloth, Delsie opened her eyes. She looked at deVigne, said “Oh, no!” in accents of deepest disgust, closed her eyes, and turned her head away.

“You know me?” he asked brusquely, fearing he hardly knew what. That her brain was disordered, or worse.

“Where’s Bobbie?” she asked in a weak voice.

“In her bed.”

“I shouldn’t have left her-”

“Indeed you should not!” he answered, anger rapidly replacing fear as he saw her wits to be intact, but the anger was truly directed against himself.

“It was you-in the woods,” she accused.

“Yes, yes. All my doing. Delsie, I’m damnably sorry.”

She closed her eyes, and they remained closed till the doctor arrived not so much later. During the interval, deVigne first sat beside her, directing a few disconnected comments to her unresponding form, then pacing the room, still talking at random. The doctor’s ministrations roused her thoroughly, especially when he probed her cut. She wailed in a loudish voice that grew no weaker when she noticed deVigne glancing worriedly over the doctor’s shoulder. After some uncomfortable minutes, the doctor closed his bag and pronounced her safe, with only a probable headache, which was to be relieved by a sleeping draught.

“No!” she declared firmly.

“Mrs. Grayshott has already had a-sedative,” deVigne explained.

“The pupils are not dilated,” the doctor pointed out. “That must have been some time ago. I recommend a few drops-”

“No!” she repeated, more firmly than before.

The poor doctor looked quite surprised at her lack of cooperation, and said that if she had the devil of a headache in the morning, she must not blame him.

“You may be sure I shan’t blame you, Doctor!” she declared in a meaningful voice, looking over his head to him whom she did blame. DeVigne shook his head slightly, to indicate she should hold her peace till the doctor was gone.

He soon left, and with a wary look, deVigne came toward the settee. “That feel better?” he asked.

She sat up and glared at him. “No doubt you are concerned that I be perfectly comfortable, after drugging me and locking me up in your house, and hitting my head with a rock!”

“I did not! Hit your head I mean. I had to stop you from barging in on the smugglers. Delsie, what in God’s name possessed you to-

“Oh, no, I am not the one who has to explain the night’s actions. You are the one who has broken half a dozen laws. I shouldn’t be in the least surprised to hear that moving smuggled brandy was included in your crimes either.”

“I wish you will lie down and relax,” he essayed placatingly.

“I have been relaxed to the point of unconsciousness for several hours already this night. What time is it anyway?”

“It is one-fifteen. Why?”

“You must hurry and find out where they’ve hidden it! Oh, do rush, Max, or they’ll be gone,” she urged, forgetting to be angry with him in her eagerness, and forgetting as well her vow never to use his Christian name.

“They’ve been gone an hour. They were there when you-you fell.”

“Was pushed!” she corrected.

“I didn’t push you. I had to stop you from dashing into the orchard. They were coming then.”

“And you there to meet them! It is no more than I expected. I daresay it is you who has been littering up the Cottage with bags of guineas.”

He dismissed this charge with no more than a baleful stare, deeming it beneath contradicting. “If you hadn’t… And how the deuce did you get out the window?” he demanded.

“I climbed down the vine.”

“You didn’t even wear a wrap. It will be a wonder if you haven’t caught your death of cold.”

“A mere wisp of pneumonia will be nothing after the rest of it.” At last she could contain her curiosity no longer, and gave over being angry with him. “Do tell me where they have been hiding it.”

“I don’t know,” he confessed shamefully.

“You don’t know? You mean we are never to discover how they did it? Oh, if I were a man I’d shoot you.”

“If you were not a foolish, stubborn, headstrong woman, we would know.”

“This beats all the rest! For you to be calling me stubborn after the way you have persisted in having you own way throughout this entire affair. Making me marry Andrew, making me leave the Cottage instead of helping me, and then not to discover the hiding place. Talk about foolish!” She stopped, too overcome to continue.

He looked a little shamefaced at these charges, and urged her once more to lie down and be calm. “We’ll know the secret of the hiding place by morning. I left a footman there to watch and discover how it is done. He hasn’t returned yet, but-”

“And likely never will!”

“There is no danger. Watling can handle himself. They were just beginning whatever it is they do, when you got hurt. Hicks said something-but I must have heard him wrong, in my anxiety. I thought he said they were moving the trees.”

A tinkle of laughter rang out. “He thinks he is playing Macbeth, with Birnam Wood coming to Dunsinane. I doubt if even Andrew could contrive that. And the trees were not men in disguise. I hope I know a tree when I see it, and a man.”

“I am happy to see your spirits recovering. When you take to bragging, I know you must feel better.”

She was beginning to feel worse from the exertion of talking, however, and sank back on the pillows.

“It is time you were in bed,” he said. “I’ll call Mrs. Forrester. Is it safe to put you back in the Rose Suite? Now that they are gone, you won’t go clambering down the vine again, I trust. You are not here under compulsion now. If you wish to return to the Cottage, pray tell me, and I shall take you in the carriage. The servants have all left, incidentally,” he added.

“I’ll stay here,” she answered with indifference.

She tried to walk, with the help of Mrs. Forrester and deVigne, but after a few unsteady steps, he lifted her into his arms, saying impatiently that he didn’t have all night to show her to her room. She was asleep before Mrs. Forrester extinguished the lamp and closed the door.

Chapter Nineteen

With a heavy gray sky and her curtains drawn, Delsie’s room remained dark till late the next morning. It was ten-thirty before she was up and dressed, and eleven before she had breakfasted. DeVigne was not in evidence, and at such a late hour, Bobbie was in the nursery having her lesson with Miss Milne. Queries of the servant giving her breakfast revealed only that his lordship was not in, which angered the widow unreasonably. Before she walked home in high dudgeon, he came in at the door, obviously excited.

“Good morning, ma’am. I hope you slept well,” he said cheerfully, regarding the plaster Mrs. Forrester had replaced, for she had no opinion of a doctor who covered up half a lady’s forehead for a tiny scratch.

“Why should I not, with half a bottle of laudanum inside me,” was her uncivil reply.

“Good, then it is time to go to the orchard.”

“Have you been there already? Do tell me all about it,” she pleaded.

“I have just returned this minute. The thing almost defies description. It will be easier to show you how it operates.”

She forgot her resentment in the exciting prospect of seeing her trees move about, and dashed to the door before him.

“You will want a coat,” he pointed out.

“I didn’t bring one with me.”

He sent a servant for one of his driving coats, and with a very long, many-caped drab coat thrown over her gown, she was ready to go. “Oh, we must take Bobbie with us,” she remembered, just at the door, causing a further delay. She remarked that there were several footmen accompanying them, standing up behind the carriage, and inquired the reason for this. “I haven’t seen such an entourage since the first day you came to see me at the school,” she roasted.

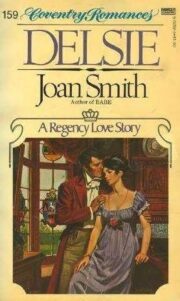

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.