“How interesting. Name your own. I am broad-minded.”

She cast a repressive glance at this venture. “This tastes like a vile medicine. And I must caution you that when you have finished this bottle, there is no more.”

“Surely you will have a glass of wine, at least. Don’t make me drink alone.”

“Here is Nellie with my dinner,” she said, as the servant came to the doorway with a tray.

“Setting up city hours, are you? Our cards will have to wait.”

While Mrs. Grayshott had her dinner, they talked of housekeepers, carriages, and a likely charity for the bags of guineas now reposing in the bank at Questnow. DeVigne, she thought, had set out to amuse and charm her, and despite her liveliest suspicions as to his reason, he succeeded.

When they had finished discussing the present, he began to ask about her past life, commenting on the odd fact that they had both lived here on the coast for years without meeting. He teased her that she must have gone a mile out of her way to avoid making his acquaintance, for he was sure he knew everyone else in the village, and could not imagine how he failed to scrape an acquaintance with his prettiest neighbor. “Not so wide-awake as Andrew, obviously,” he said, with his eyes lingering on her flushing countenance.

“Very true, and not so fast either. Why, he proposed before he was inside my door two minutes!”

“And here I was afraid I was rushing things. But you were not a widow in those days,” he pointed out.

“No, and you were never quite so shabby as your brother-in-law,” she complimented grandly.

“Thank you,” he said with a hard stare. “We have managed to converse for half an hour without coming to cuffs, and I refuse to take umbrage at that challenging statement. You have earned a glass of Andrew’s excellent sherry, and I shall pamper you by running to fetch it.”

“That is not at all necessary. There are both footmen and serving girls all over the place now. Just ring the bell.”

“No, no, we don’t want our private coze interrupted by servants,” he answered, arising to go to the dining room himself. This excuse was sufficiently flattering to please her. As she sat alone smiling, she had no suspicion that deVigne’s waiting on her had a more devious motive. From his pocket he took a vial of colorless liquid and poured a hefty dollop of it into her glass, added the sherry, and stirred it up,

The unsuspecting lady accepted it with gracious thanks a moment later and took a sip, detecting nothing odd in the taste, as she was not a habitual wine drinker. After one sip, she set the glass aside and took up her embroidery needle. “Do you like this design?” she asked her companion, passing him the pattern she used, an intertwined bouquet of roses and greenery.

“Very nice, but I am of the opinion ladies waste their time and eyes on all this needlework, which is, after all, only to be sat on.”

“It is to be admired before one sits, and after one arises, and at any odd time one passes through the dining room for any reason. It is too nice to sit on, though, isn’t it?”

“A great deal too pretty. Why don’t you frame it?”

“If Andrew were here, he would devise an excellent contraption allowing the seat of the chair to be taken up and hung on the wall between meals. He was very ingenious mechanically. So clever, the little doll he made for Bobbie, that really walks, though with a very odd gait, I must confess.”

“Yes, he had an unusual talent in that line. The Cambridge men are better scientists, I think. I was at Oxford myself. You aren’t drinking your wine, cousin.”

She lifted the glass and took another sip. “Sir Harold, too, I take it, was an Oxford man?”

“Yes, Christ Church, about a million years ago. He plans to donate his library to the college when he passes on.”

She stifled a yawn with her hand and blinked twice. “Goodness, it is only nine-thirty, and already I am beginning to feel sleepy.”

“A sad comment on my company. May I help myself to another glass of brandy?”

“Certainly.” She made to arise to get it herself, but he gestured her back. “Perhaps I should have…” She stopped and shook her head, to rouse her tired brain.

“Yes, you were saying?” he asked over his shoulder from the side table, where he stood filling his glass. He looked at her closely.

“I should have kept one of those barrels that were in the cellar. I shan’t have any brandy to serve you once that decanter is empty.”

“I shall provide myself from the generous quantity you gave me,” he answered, coming back to his chair.

“It is very warm in here, is it not?” Even as she spoke her lids became so heavy she could scarcely keep them open. “I must move my chair back. I am too close to the fire.” He helped her in this job, and she stumbled against him. “Sorry. I feel a trifle dizzy.”

His hand was firm on her arm, steadying her. “Have another sip of your wine. It will clear your head.” He handed the glass to her, but she was too unsteady to hold it. He tilted it to her lips. She took one swallow. He continued holding it, saying, “Have another. It will make you feel better.” She drained the glass, hardly aware what she was doing now. He had to guide her into her chair. She sat with her head back against the rest and closed her eyes for a moment.

Suddenly the eyes flew open wide. Shaking herself, she lunged forward. For a moment she looked at him, saying nothing. Her senses reeled, but through the mists she began to realize this was not a sudden fit of fatigue that had come over her.

“You!” she said, in an accusing tone. “You drugged… the wine. Oh!” She fell back, unconscious, her head tumbling to one side.

He observed her silently for a moment, then shook her arm, “Delsie. Can you hear me?” She made no response, but only sunk deeper into her chair.

He turned and left the room to call his footmen to bring the carriage to the front door. He took up an afghan from the sofa, wrapped it around her sleeping form, and lifted her bodily from the chair, then walked quickly to the door and took her out and placed her in the waiting carriage.

“To the Hall,” he said to his groom, climbed in beside her, and they were off. He supported her with an arm around her waist, smiling softly to himself in the darkness as they accomplished the short drive to the Hall, where she was transported into the house in his arms.

His housekeeper was waiting for him. That capable dame had provided the other servants with jobs belowstairs. It was only she who accompanied him to the Rose Guest Suite, where Delsie was placed on a bed.

“How did everything go?” the woman asked.

“Fine. I’m afraid I rushed it a little. It is not yet ten o’clock, and I don’t know how long the laudanum will last. We’d better lock her in, just in case.”

“How much did you give her?”

“About ten drops. She is not accustomed to it. She was drowsy after a couple of sips. I could hardly get her to finish the drink.”

“She’ll be asleep for four or five hours. We’ll turn the lock just in case. I’ll stay nearby and come and check every half hour. Sooner if I hear any motion.”

“She’ll be all right.” He rubbed his hands in a self-congratulatory way. “I’m darting back to the Cottage. I wouldn’t want to miss the finale. I’ll be here by the time Mrs. Grayshott comes to. There will be fireworks, or I miss my bet. Is Bobbie asleep?”

“An hour ago.”

“Good. Thank you, Mrs. Forrester. You are an angel.”

“Funny I don’t feel like one,” the woman answered, looking at the inert form on the bed.

“Better a sleeping draught than a broken skull,” he replied, and left.

DeVigne went to his room, changed quickly into old dark clothes, then went to the stable and got his favorite mount saddled to ride back to the Cottage. Four footmen were impatiently awaiting his return, as were Nellie and Olive. The girls were sent back to the Hall, escorted by Lady Jane’s footmen, and from the raillery and merriment going forth between them all, it was clear the proceedings were no surprise to any of them. This left only deVigne and his own two men at the Cottage. They stationed themselves in a semicircle around the edge of the orchard, on the far side from the building. DeVigne was determined that between the three of them, they would discover the secret hiding place of the brandy. His own interest centered on the two runted apple trees, but try as he might, he could think of no place of concealment anywhere near them.

It was fast approaching eleven o’clock as the three men settled into their various hiding places, eyes and ears alert for the first sight or sound of company. No thought of heroism or battle disturbed them. Their mission was only to remain out of sight and discover where the smugglers had secreted their goods. If the elder footman happened to recognize his brother-in-law as being of the “gentlemen,” as he had strong hopes of doing, he would do no more than roast him the next time they met. DeVigne was similarly interested to see whether Clancy Grayshott took any active part in the goings-on. He knew now he was the manager, but doubted he would see him tonight.

An hour had not seemed, in anticipation, a long time to wait, but in the actual crouching posture chosen, it seemed very long indeed. At a quarter to twelve deVigne decided he would take a very quiet, short walk to stretch his legs and be back at his post before midnight. The land surrounding the Cottage was all his own, and he had no fear of running into the gentlemen there. They would come up from the road bordering the ocean and fronting the Cottage. He stalked through the spinney, making as little noise as possible. Then suddenly he came to a dead halt. There were soft footfalls hurrying past him, to the right. “They’re using my land!” flashed through his head. A grim, determined expression settled on his features, as he turned to give chase.

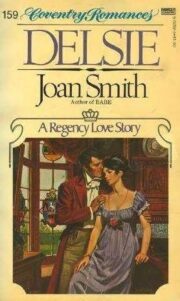

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.