As the carriage wended its familiar way down the lane to the post road, Delsie said to her stepdaughter, “Are you happy to be coming home at last?”

“Yes, but I’ll like it better when we’re all living together at the Hall. Uncle Max has five kittens in the barn.”

Max cleared his throat, and ran a finger around his collar.

“What do you mean? We are not moving to the Hall,” Delsie said to her daughter.

“Uncle Max says we are. Didn’t you, Uncle Max?”

“That is not exactly what I said,” he parried.

With a barely concealed smile, Miss Milne said that perhaps Lord deVigne would give Bobbie one of his kittens.

“I don’t want one. I want them all,” she replied.

“Precocious. You are turning into a woman already,” her uncle complimented her.

At the Cottage, Miss Milne took her charge upstairs, and Mrs. Grayshott at once rounded on deVigne. “You know I promised Andrew faithfully I would look after Roberta. I hope you have not been giving her the idea she is to go to you. I don’t know how you think I should allow it, when the main reason I married Andrew was to provide a guardian for her.”

“You were not listening very carefully. What she said was that we would all be living together at the Hall.”

Having a very good inkling as to his meaning, the widow blushed up to her eyes, and pointed out that such a scheme was entirely ineligible, for a widow in no way related to him to be moving into a bachelor’s establishment.

“That is true, and we would have to arrange some relationship,” he answered reasonably.

“There is no way it could be arranged.”

“One suffers to think of a schoolteacher having so little use of her wits. It could be arranged very easily by our marrying.”

“You would do anything to get hold of Roberta!” she accused him.

“Yes, I am quite determined to get my clutches on Roberta!” he agreed, smiling. “I am resigned to having that charge thrown at my head every time you feel out of sorts, which happens remarkably often, by the by. But so long as we both know it is merely a stick to beat me with, I am willing to accept it.”

“I wonder at your lack of propriety! Andrew scarcely cold in his grave-”

“He must be cooled down considerably. It is December, after all.”

“I was speaking metaphorically.”

“That’s what I get for making up to a schoolmistress. How long must we wait?”

“Till hell freezes over.”

“That should cool him down all right. Do you mean we must wait out the whole year?”

“I meant nothing of the sort!”

“Good, I think six months more than enough myself.”

“You know I didn’t mean that.”

“I am ravished at your eagerness, but really we ought to wait till you are at least in half mourning, don’t you think?”

“You are being purposely obtuse. I can’t possibly marry you! Two marriages in one year. It is monstrous.”

“True, but it is already December, and will soon be next year. We’ll consign your nominal marriage to Andrew to this year, and-”

“Yes, I see what you are about. Trying to rush me into it again, before I have time to think. Don’t forget to point out all the advantages that will accrue me. A domineering, mulish husband who doesn’t even stick at drugging and kidnapping me, a vastly superior home, a title-”

“You’re doing a pretty good job of convincing yourself. Only think, never again to be called by the odious name of Mrs. Grayshott. That must bear heavily on the side of the advantages.”

“We would be laughingstocks in the village,” she objected weakly, and looked hopefully to him for refutation.

“They could well do with a few laughs in Questnow. Things are remarkably flat in the winter. Of course it bothers me enormously what Mr. Umpton and Miss Frisk think, and I’m sure you too shrink from doing anything they would dislike.”

“It would almost be worth putting up with you to see Umpton stare.”

“No price is too high to pay for that sort of a treat. We’ll call on him together, and both watch him stare,” he answered gravely, his lips only a little unsteady.

“I said almost worth it. Jane warned me-not that you haven’t already locked me up in a room and beat me.”

“No, no, not beat! Be fair. A crack on the skull is not a beating. I save that for after the wedding. Or were you speaking metaphorically again, referring to my having bested you in the matter of rooting you out of the Cottage last night?”

“You cheated anyway.”

“I took a slightly unfair advantage.” He advanced toward her and removed the driving cape from her shoulders, tossing it on a chair. “I don’t mean to do so again, Delsie,” he said, looking at her intently, with all the levity gone from his voice. “I was horrified when I saw what I had done to you last night. Indeed, ever since this smuggling business reared its ugly head I have regretted dragging you into it.” He touched the plaster on her forehead, and ran one finger slowly down her cheek. “Can you forgive me for that?”

“It was an accident. I know you didn’t do it on purpose.”

“But I did it, and I shan’t forgive myself. I was afraid I’d hurt you badly-”

“Don’t be ridiculous-a mere bump on the head,” she laughed unsteadily.

“You are generous, but I vowed I would make it up to you.”

“Is that why you are offering for me?” she demanded.

“You are foolish beyond belief,” he said angrily, and pulled her into his arms. “I am marrying you because I don’t want you to leave us, ever. Because I have never been so happy as since you came to us. Because I love you, Delsie Sommers.” He looked hard at her face for a few seconds, then closed his eyes and kissed her. When he released her several moments later, he added, “And I am conceited enough to think half your fits of pique are due to loving me, despite your own better judgment.”

“I am not really Delsie Sommers anymore,” she answered dreamily.

“You are, really,” he disagreed firmly, and bent his head to kiss her again.

They were interrupted by the sound of feet thumping on the stairs and Bobbie came into the room. “I heard somebody coming,” she said.

“Your hearing is definitely impaired,” deVigne told her, displeased at her arrival.

“No, it isn’t. I hear very good.”

“Very well,” Delsie corrected automatically.

“See, Mama says so too. But you want to get rid of me so you can be alone with Mama. I heard Sally say at the Hall you’re always running to Mama.” On this remark she ran to the door.

“I have been found out,” he informed Delsie. “Even the servants and a child see through me. ‘Always running to Mama.’”

“She shouldn’t be gossiping with the servants.”

“Only eavesdropping. Sharp as a tack, our Bobbie.”

It was soon clear her hearing was also sharp. There had been a cart driven up outside, unheard by the two in the saloon, who were so happily occupied otherwise. It was Delsie’s ex-students, come to inquire whether Mrs. Grayshott still wanted their services. These were gratefully accepted, and it was arranged for the girls to return the next morning with their belongings to take up work at the Cottage.

“Word must be out that we no longer run a smuggling den here,” deVigne said.

“How flat it will be, with no pixies in the garden and no bags of gold regularly deposited under the tree.”

“We shall do our poor best to keep you entertained, Miss Sommers.”

“Mrs. Grayshott.”

“How strange, now that you are about to be rid of the name, you develop this inexplicable passion for it. I wish to forget I ever cajoled you into marrying Andrew. Though I suppose otherwise I should never have come to know you. I had no suspicion, to see you in the village, that we should suit in the least. A regular little nun, I thought. Jane is wiser. Nonesuch, she said, and she was right.”

“Lady Jane will not be happy with this business. She has picked out a Miss Haversham for your wife, and I hope she will not be too disappointed at your refusing to have her.”

“Miss Haversham?” he asked, frowning. “She is sixty-five, give or take a decade.”

“No, no. It must be a different Miss Haversham, a younger one.”

“The younger one is sixty-five; she has an elder sister eighty or so. Where did you get this idea?”

“She told me.”

“The old terror!” he exclaimed, laughing. “She has been trying to make you jealous. Observing my penchant for your company, as did the servants, she wanted to give you a nudge.”

“The sly creature! Let us not tell her we are to be married, and watch her finagle.”

The secret lasted less than halfway through dinner that evening. Jane first observed that the two had dispensed with formal names and titles and were on a first-name basis. When deVigne inadvertently mentioned, during a discussion of hiring a housekeeper, that her services would be very temporary and Mrs. Lambton would be good enough for a few months, she was onto them, but kept up the game.

“A few months? Oh, she is young enough to last a few years, Max.”

“I meant years,” he said, with a conscious look at Delsie, who smiled sheepishly.

“Of course you did,” Lady Jane smiled knowingly. “Why should Delsie only require her services for six months, till she is out of deep mourning? Dear me, there could be no reason. None in the world. It is not as though she will be leaving the Cottage.”

“Certainly not,” Sir Harold added foolishly, the only one at the table who had not perceived what was going on before his eyes. His wife turned a withering look on him.

“For, of course, you will not be leaving us,” Jane continued, her irony becoming stronger by the moment.

“Oh, no,” Delsie agreed.

“Or moving to the Hall,” Jane said at last, with a piercing observation of the pair of culprits.

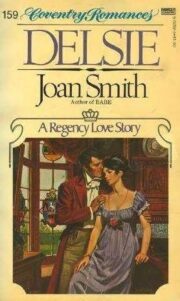

"Delsie" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Delsie". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Delsie" друзьям в соцсетях.