“Oh—! Dear Mrs Barling! I’ll come at once!” Emma said, and went back into the ballroom, bearing her reluctant spouse with her.

Stonor followed them, but the Viscount lingered in the hall to adjust his neckcloth, having caught sight of himself in a mirror that hung beside the double-doors into the drawing-room. He was not a dandy; he would have repudiated without hesitation Lady Bugle’s assertion that he was a Pink of the Ton; but he was undeniably one of the Smarts, and the glimpse of himself in wilting shirt-points, and a slightly disarranged neckcloth came as a disagreeable shock to him. There was little he could do to restore their starched rigidity to the points of his shirt-collar, but a few deft touches were all that was needed to repair the folds of his neckcloth. Having bestowed these upon it, he turned away, gave his shirt-bands a judicious twitch or two, and was just about to go back into the ballroom when a feeling that he was not alone, as he had supposed himself to be, made him look up, and cast a swift glance round the hall. No one was in sight, but when he raised his eyes towards the upper floor he found that he was being watched by a pair of wondering, innocent eyes which were set in a charming little face, framed by the bannisters through which its owner was looking. He smiled, guessing that it belonged to one of the younger daughters of the house: possibly a member of the schoolroom-party, but more probably one of the nursery-children, and said, as he saw that she was about to run away in evident alarm: “Oh, don’t run away! I promise I won’t eat you—or tell tales of you to your mama!”

The big eyes widened, in mingled fear and doubt. “You couldn’t!” said the lady. “I haven’t got a mama! She’s been dead for years! I don’t think I have a papa either, though that is by no means a certain thing! Oh, don’t come up! Pray don’t come up, sir! They would be so vexed!”

He had mounted half-way up the first flight of stairs, but he paused at this urgent entreaty, saying, between amusement and curiosity: “No mama? But are you not one of Sir Thomas’s daughters?”

“Oh, no!” she replied, still in that hushed, scared voice. “I’m not related to him, because being married to my aunt does not make him a true uncle—does it?”

“No, no!” he assured her. “It makes him nothing more than an uncle-in-law. But even so I find it hard to believe that he would be cross with you for peeping through those bannisters at the ladies in their smart ball-dresses, and the gentlemen trying to straighten their neckcloths!”

“It isn’t him!”she said, with an apprehensive look over his head towards the drawing-room. “It’s Aunt Bugle, and Lucasta! Oh, pray, sir, go away, before anyone sees you on the stairs, and asks you what you are doing there! You would be obliged to say that you had been talking to me, and that would get me into trouble again!”

His amusement grew, and also his curiosity. “Well, no one is going to see me on the stairs, because I am coming up to further my acquaintance with you, you engaging elf! Oh, don’t look so scared! Recollect that I’ve promised I won’t eat you! And talking of eating,” he added, remembering his own childhood, “shall I bring you some of the tarts and jellies I’ve seen laid out for supper? I shall say I want them for my cousin, so you needn’t be afraid that anyone will know you ate them!”

She had seemed to be on the point of scrambling to her feet, and beating a hasty retreat, but these words checked her. She stared at him for a moment, and then gave a soft little chuckle, and said: “No, thank you, sir! I had supper hours ago, with Oenone, and Corinna—and Miss Mudford, of course—and my aunt directed the cook to set aside some of the tarts and cakes for the schoolroom supper. So I am not at all hungry. In fact, I’m never hungry, because my aunt doesn’t starve me! But I am very much obliged to you for being so kind—which I thought you were, the instant you looked up, and smiled at me!”

“Ah, so you are one of the schoolroom-girls, are you?” he said, mounting the rest of the stairs till he stood at the head of the first flight, on the upper hall. “Then I owe you an apology, for I took you for one of the nursery-babies!” He broke off, for she was on her feet, and although the only light illuminating the scene came from the candles burning in the chandelier that hung in the hall below there was enough to show him that she was considerably older than he had supposed.

She smiled shyly up at him, and said: “People nearly always do. It is because I’m such a wretched little dab of a creature, and a severe mortification to me—particularly when I’m amongst my cousins, who are all so tall that I feel a mere squab beside them! At least Lucasta and Oenone and Corinna are tall, and Dianeme is very well grown, so I expect she will be too. Perenna is only just out of leading-strings, so one can’t tell about her yet,”

Slightly stunned, he said faintly: “Are you sure you have your cousins’ names correctly? Did you say Dianeme? And Perenna?’

“Yes,” she answered, with another of her soft chuckles. “You see, when she was very young my aunt was much addicted to poetry, and her papa had a library crammed with old books. That’s how she came upon the poems of Robert Herrick. She has the book to this day, and she showed it to me once, when I ventured to ask her why my cousins have such peculiar names. She said she thought them so pretty, and not commonplace, like Maria, and Eliza, and Jane. She wished very much to call Lucasta Electra, but thought it more prudent to name her after her godmama, from whom Lucasta has Expectations. Though I shouldn’t think, myself, that anything will come of it,” she added, in a reflective tone, “because she’s as cantankersome as old Lady Bugle was used to be, and she doesn’t seem to me even to like Lucasta, or to admire her beauty, which one must own to be unjust, for Lucasta always behaves to her most obligingly, and it must be acknowledged that she is beautiful!”

“Very true!” he agreed, his voice grave, but his eyes full of laughter. “And are—er—Oenone and Corinna beautiful too? They should be, with such names as those!”

“Well,” she said temperately, “old Lady Bugle was for ever telling my aunt that neither of them has beauty enough to figure in London, but I think they are both very pretty, though not, of course, to compare with Lucasta. And as for their names—” She choked on a smothered giggle, and a mischievous gleam shone in her eyes. She raised them to his face, and confided: “Oenone doesn’t dislike hers, but Corinna perfectly detests hers, because Stonor discovered the poem called Corinna’s Going a Maying, and read it to the other boys, so that they instantly took to calling her Sweet Slug-a-bed, and shouting to her outside her door in the morning to Get up, get up for shame, which put her in such a flame that she actually tried to come to cuffs with her papa for having allowed my aunt to saddle her with such a silly, outmoded name. Which was improper, of course, but one can’t but sympathize with her.”

“No, indeed! And what was her papa’s reply to this very just rebuke?” he enquired, much entertained by this artless recital.

“Oh, he merely said that she might think herself fortunate that she hadn’t been christened Sappho, and that if it hadn’t been for him she would have been. It doesn’t sound to me any worse than Corinna, but I believe there was a Greek person of that name who wasn’t at all the thing. Oh, pray don’t laugh so loud, sir!”

He had uttered an involuntary crack of laughter, but he checked it, and begged pardon. He had by this time had time to assimilate the details of her dress and person, and had realized that her figure was elegant, and that her dress had been adapted rather unskilfully from one originally made for a much bigger girl. He also realized, being pretty well experienced in such matters, that it was a trifle dowdy, and that her soft brown ringlets had not enjoyed the ministrations of a hairdresser. It was the fashion for ladies to have their locks cropped and curled, or twisted into high Grecian knots from which carefully brushed and pomaded clusters of curls fell over their ears; but this child’s hair fell loosely from a ribbon tied round her head, several strands escaping from it, which gave her a somewhat dishevelled appearance.

Desford said abruptly: “How old are you, my child? Sixteen? Seventeen?”

“Oh, no, I am much older than that!” she replied. “I’m as old as Lucasta—all but a few weeks!”

“Then why are you not downstairs, dancing with the rest of them?” he demanded. “You must surely be out!”

“No, I’m not,” she said. “I don’t suppose I ever shall be, either. Unless my papa turns out not to be dead, and comes home to take care of me himself. But I don’t think that at all likely, and even if he did come home it wouldn’t be of the least use, because he seems never to have sixpence to scratch with. I am afraid he is not a very respectable person. My aunt says he was obliged to go abroad on account of being monstrously in debt.” She sighed, and said wistfully: “I know that one ought not criticize one’s father, but I can’t help feeling that it was just a little thoughtless of him to abandon me.”

“Do you mean that he left you in your aunt’s charge?” he asked, his brows drawing together. “He can’t have abandoned you!”

“Well, he did,” she said. “And it was horridly uncomfortable, I can tell you, sir! I was still at school, in Bath, you see—and I must own that Papa did pay the bills, when he was in funds, and Miss Fletching was very kind, and she never told me that he had stopped doing so until she was obliged to realize that he wasn’t going to remember that he owed her for a whole year. She disclosed to me afterwards that for a long time she expected to get a letter from him, or even a visit, for he did sometimes come down to see me. And it seems he had never been very punctual in paying Miss Fletching, so that she was quite in the habit of waiting. And I fancy she had a tendre for him, because she was for ever saying what a handsome man he was, and how particularly affable, and what distinguished manners he had. She was fond of me, too: she said it was because I had lived with her for such a long time, which I had, for Papa placed me in the school when my mama died, and I was only eight years old then, and lived at school all the year round.”

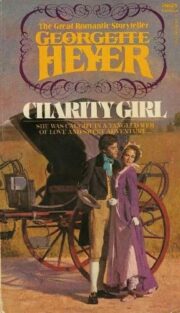

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.