“I should think not indeed!” said Gilbert. “Why, she’s downright knocker-faced!”

Lady Emborough called him sharply to order for so rudely exaggerating Miss Windle’s appearance; but when, on the following evening, the Viscount was presented to the lady he could not feel that Gilbert had been unjust. But he felt also that her homeliness would not have struck him so forcibly had not Lady Bugle caused her to stand side by side with Lucasta Bugle, to receive the guests.

Lucasta was certainly something quite out of the ordinary way, for besides a countenance of classic beauty her figure was good, and her teeth, when she smiled, were seen to be very even, and as white as whalebone. She had luxuriant hair, which only jealous rivals stigmatized as gingery: it was, in fact, the colour of ripening corn; and her proud mama had frequently been known, when accepting compliments on her burnished curls, to whisper confidentially that they had never to be papered. She seemed to have acquired habits of easy intercourse, in spite of the abrupt curtailment of her first season, for she betrayed none of the signs of shyness which so often made it difficult for their partners at a ball to talk to girls who had only just emerged from the schoolroom. Her manners were assured; she had a fund of social chitchat at her tongue’s end; she was all delight and cordiality towards her mama’s guests; she was animated, and laughed a great deal; and seemed to be an expert in the art of light-hearted flirtation.

The Viscount had the honour of standing up with her for the dance that was forming when the Emborough party arrived, and since he was more expert in this art than she was he gratified her by responding in the most obliging way to the encouragement he received to pay her just the sort of compliments he judged likely to be the most acceptable. His cousin Edward, indignantly observing the progress he was making into the Beauty’s good graces, and the arch, laughing looks which she threw at him, was torn between envy of his address, and cynical reflections on the advantages attached to being the heir to an Earldom. For these he took himself severely to task, telling himself, with dogged loyalty, that the divine Lucasta was merely trying to put a stranger at his ease. But when Gilbert, who had never contrived to grow higher in the Beauty’s esteem than had his elder brother, encountered him for a fleeting moment, and said, with a malicious wink: “Des is devilish taken with her, ain’t he?” he was unable to disagree. All he could think of to say was that he was sure it was no wonder. But when he saw his divinity waltzing, a little later in the evening, with Desford, he would, had he not been a very goodnatured young man, have taken his cousin in violent dislike. The waltz was still considered by old-fashioned persons to be an improper dance, and was seldom played at country assemblies. One or two dashing hostesses has caused it to be played, but Ned, having painstakingly mastered the steps, had found that he had wasted his time: Lucasta never waltzed.

He had not expected that it would figure amongst the country dances and the boulangers offered to the company in the Bugles’ establishment, but Lady Bugle, hopeful that Lady Emborough would bring to her little party her tonnish nephew, had warned the musicians to be prepared to strike up for one, and had told Lucasta that if the Viscount did happen to ask her to dance it with him she might do so.

“For there can be no objection to your doing so here, my love, amongst our particular friends. In London, of course, the case would be different—until, as I need scarcely remind you, you have been approved by the Patronesses of Almacks; but I should be excessively mortified if any of our guests thought it a dowdy party, and if dear Lady Emborough does bring Lord Desford to it you may depend upon it that he will expect to hear waltzes played, for he is quite one of the Pinks of the Ton, you know!”

Lord Desford did ask her, saying, as he led her off the floor at the end of the country dance, that he hoped she would stand up with him again, and adding, with his attractive smile: “Dare I ask you to waltz with me? Or do you frown on the waltz in Hampshire? I wonder if my aunt does? How stupid it was of me not to have asked her! Now, don’t, I do beg of you, Miss Bugle, tell me that I’ve committed a social solecism!”

She laughed, and said: “No, indeed you have not! I do waltz, but whether Mama will permit me to do so in public is another matter!”

“Then I shall instantly ask Mama’s permission to waltz with you!” he said.

This having been granted, he was presently seen twirling round the room with an arm lightly encircling Lucasta’s trim waist: a spectacle which Lady Bugle regarded with complacency, but which was watched by the Viscount’s two cousins, and by several other young gentlemen equally enamoured of the Beauty, with no pleasure at all.

After this, the Viscount did his duty by Miss Windle, and Miss Montsale, and then asked his cousin Emma to stand up with him.

“For heaven’s sake, Ashley, don’t ask me to dance, but take me out of this insufferably hot room!” replied Mrs Redgrave, who had inherited much of her mother’s forthrightness.

“With the greatest pleasure on earth, cousin!” he replied, offering his arm. “I’ve been uneasily aware for the past half-hour that my shirt-points are beginning to wilt! We will walk over to the doorway, as though we wished to exchange a word with Mortimer, and slip out of the room while the next set is forming. I daresay no one will notice our absence.”

“I don’t care a rush if they do notice it!” declared Mrs Redgrave, vigorously fanning herself. “People have no business to hold assemblies on such a sultry night as this! They might at least have opened a window!”

“Oh, they never do!” said Desford. “Surely you must know, Emma, that it is only imprudent young people who open windows on even the hottest of nights! Thereby causing their elders to suffer all the ills which, I am assured, arise from sitting in a draught, and exposing themselves to even worse dangers. Mortimer, why are you not doing your duty like a man, instead of lounging there and holding up your nose at the company?”

“I wasn’t!” said Mr Redgrave indignantly. “The thing is that it’s a dashed sight too hot for dancing—and no one thinks anything of it when we old married men don’t choose to dance!”

“Quoth the graybeard!” murmured Desford.

“Be quiet, wretch!” Emma admonished him. “I won’t have poor Mortimer roasted! Recollect that although he is not so very many years older than you he is much fatter!”

“There’s an archwife for you!” said Mr Redgrave. “If you take my advice, Des, you’ll steer wide of parson’s mousetrap!”

“Thank you, I mean to! The melancholy sight of you living under the cat’s foot is enough to make any man beware!”

Mr Redgrave grinned, but said that Des had hit the nail on the head, adding that he had grown to be a regular Jerry-sneak. Emma knew very well that this inelegant expression signified a henpecked husband, but said with dignity that she didn’t understand cant terms. She then said, as both gentlemen laughed, that they were a couple of horrid rudesbys.

“To be sure we are!” cordially agreed her life’s companion. “You know, if you mean to take part in this dance, the pair of you, you’d best join the set before it’s too late!”

But when he learned that so far from joining the set they were going in search of a little fresh air he instantly said, with considerable aplomb, that having watched Des desperately flirting with Miss Bugle he was dashed well going to see to it that he didn’t get the chance to make up to Emma too.

So the three of them passed through the wide double-doors which stood open into the hall. Several people were gathered there, in small groups, most of the ladies fanning themselves, and the gentlemen surreptitiously wiping their heated brows; but Mrs Redgrave had the advantage over them in knowing the geography of the house, and she led her two cavaliers past the stairway to the back of the hall, and through a door which gave access to the gardens. The air was rather more oppressive than it had been during the day, but in comparison to the conditions within the house it was refreshing enough to cause Mr Redgrave to draw a deep breath, and let it go in a vulgar: “Phew!” He then expressed a wistful desire for a cigarillo, but as his wife recognized this as a mere attempt to hoax her into begging him not to do anything so improper as to light a cigarillo at a ball she paid no attention to it, but tucked her hand in his arm, and strolled on to the lawn. The moon was at the full, but was every now and then hidden by clouds drifting across the sky. Summer lightning flickered, and Mr Redgrave said that he wouldn’t be surprised if they were in for a storm. A few minutes later a distant rumble made Emma think that perhaps it was time they returned to the ballroom. Her disposition was in general calm, but she had a nervous dread of thunderstorms. Any of her brothers would have scoffed at her fears, but her husband and her cousin were more understanding, and neither scoffed nor tried to convince her that the storm was not imminent.

When they re-entered the house there was no one in the hall, but just as Mr Redgrave softly shut the door into the garden Stonor Bugle came out of the ballroom, and exclaimed: “So there you are! I’ve been looking for you all over!”

“Oh, dear!” said Emma guiltily. “I hoped no one would notice it if I slipped away for a few minutes! It is such a hot night, isn’t it?”

He laughed heartily at this. “Ay! Devilish, ain’t it? I only wish I could sherry off into the garden, but I can’t, you know! My mother would comb my hair with a joint-stool if I did! The thing is that old Mrs Barling has been asking for you, ma’am: says she hasn’t seen you since time out of mind, and has been peering round the room after you ever since someone told her you was here,”

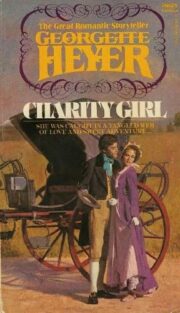

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.