“Yes, she’s as good as wheat,” agreed Lady Emborough, in a somewhat gloomy voice. “But she ain’t a girl, Desford: she’s older than you are! And no one has ever offered for her! Heaven knows I shouldn’t know what to do without her, but I can’t be glad to see her dwindling into an old maid! It ain’t that the men don’t like her: they do, but they don’t fall in love with her. She’s like Hetta Silverdale—except that Hetta’s a very well-looking girl, and my poor Rachel—well, there can be no denying that she’s something of a Homely Joan! But each of them would make any man an excellent wife—a much better wife than my Theresa there, who is so full of whims and crotchets that I never expected her to go off at all, far less to attach such a good bargain as John Thimbleby!”

Aware that Mr Thimbleby was seated well within earshot, the Viscount shot an involuntary glance at him. He was relieved to see a most appreciative twinkle in this gentleman’s eye, and to receive from him something suspiciously like a wink. He was thus able to reply to his aunt with perfect equanimity: “Very true, ma’am! But there is no accounting for tastes, you know! However, you’re out when you say that Hetta has no suitors! I could name you at least four very eligible partis whom she might have had for the lifting of a finger. Indeed, when I saw her this morning I found her entertaining two more of them! Perhaps neither she nor my cousin Rachel wishes to become a mere wife!”

“Gammon!” said her ladyship crudely. “Show me the female who doesn’t hope for marriage, and I’ll show you a lunatic past praying for! Yes, and if you wish to know what I think—not that I suppose you do!—you’re a shuttlehead not to have married Hetta when I daresay she was yours for the asking!”

The Viscount was annoyed, and betrayed it by a slight contraction of his brows, and the careful civility with which he said: “You are mistaken, my dear aunt: Hetta was never mine for the asking. Neither of us has ever wished for a closer relationship than that of the friendship we have always enjoyed—and, I trust, may always enjoy!”

As little as Lady Emborough resented the quiet checks her husband imposed upon her exuberance did she resent a deserved snub. She replied, laughing: “That’s the hammer! Quite right to give me a setdown, for what you do is no business of mine! Emborough is for ever scolding me for being too wide in the mouth! But, wit-cracking apart, Desford, isn’t it time you were thinking of matrimony? I don’t mean Hetta, for if you don’t fancy each other there’s nothing to be said about that, but with Horace still in France, and Simon, from all I hear, sowing even more wild oats than your father did, in his day, I can’t but feel that you do owe it to your father to give him a grandson or two—legitimate ones, I mean!”

This made the Viscount burst out laughing, and effectually banished his vexation. “Aunt Sophronia,” he said, “you are quite abominable! Did anyone ever tell you so? But you are right, for all that, as I’ve lately been brought to realize. It is clearly time that I brought my delightfully untrammelled life to an end. The only difficulty is that I have yet to meet any female who will both meet with Papa’s approval, and inspire me with the smallest desire to become riveted to her for life!”

“You are a great deal too nice in your requirements,” she told him severely; but added, after a moment’s reflection: “Not but what I don’t wish any of my children to marry anyone for whom they don’t feel a decided preference. When I was a girl, you know, most of us married to oblige our parents. Why, even my bosom-bow in those days did so, though she positively disliked the man to whom her parents betrothed her! And a vilely unhappy marriage it was! But your grandfather, my dear Ashley, having himself been forced to contract an alliance which was far from happy, was resolute in his determination that none of his children should find themselves in a similar situation. And nothing, you will agree, could have been more felicitous than the result of his liberality of mind! To be sure, there were only three of us, and your Aunt Jane died before you were born, but when I married Emborough, and Everard married your dear mama, no one could have been more delighted than your grandfather!”

“I am sorry he died before I was out of short coats,” Desford remarked. “I have no memory of him, but from all I have heard about him from you, and from Mama, I wish that I had had the privilege of knowing him.”

“Yes, you’d have liked him,” she nodded. “What’s more, he’d have liked you! And if your father hadn’t waited until he was more than thirty before he got married to your mama you would have known him! And why Wroxton should glump at you for doing exactly what he did himself is something I don’t understand, or wish to understand! There, you be off to play billiards with your cousins, and the Montsale girl, before I get to be as cross as crabs, which they say I always do when I talk about your father!”

He was very ready to obey her, and she did not again revert to the subject. He stayed for a week in Hampshire, and passed his time very pleasurably. After the exigencies of the Season, with its ceaseless breakfasts, balls, routs, race-parties at Ascot, opera-parties, convivial gatherings at Cribb’s Parlour, evenings spent at Watier’s, not to mention the numerous picnics, and al fresco entertainments ranging from quite ordinary parties to some, given by ambitious hostesses, so daringly original that they were talked of for at least three days, the lazy, unexacting life at Hazelfield exactly suited his humour. If one visited the Emboroughs there was no need to fear that every moment of every day would have been planned, or that you would be dragged to explore some ruin or local beauty spot when all you wished to do was to go for a strolling walk with some other like-minded members of the party. Lady Emborough never made elaborate plans for the entertainment of her guests. She merely fed them very well, and saw to it that whatever facilities were necessary to enable them to engage in such sports or exercises as they favoured were always at hand; and if any amusement, such as a race-meeting, happened to be taking place she informed them that carriages were ready to take them to it, but if anyone felt disinclined to go racing he had only to say so, and need not fear that she would be offended.

She adhered strictly to this admirable course when she disclosed to Desford that she had promised to attend a party on the last night of his visit, taking with her her two elder sons, as many of her daughters as she thought proper, and any of the guests she would no doubt have staying with her at Hazelfield and who did not despise quite a small, country ball. “I shall be obliged to go,” she said, in the resigned voice of one who did not expect to derive any pleasure from the offered festivity. “And Emma and Mortimer mean to go too. Theresa has cried off, but that won’t surprise Lady Bugle, for she knows very well that Theresa is increasing. The Montsales don’t wish to go either, and there’s no reason why they should when I must go, and can chaperon Mary for them. Ned and Gil mean to go, but Christian don’t: he hasn’t started to dangle after pretty girls yet. And if you don’t fancy it, Desford, there’s no reason why you shouldn’t remain here, and play whist with the Montsales and John Thimbleby! In fact, I strongly advise you to do so, because it’s my belief you’ll think the Bugles’ party a dead bore.”

“Think it a dead bore when that glorious creature will be present?” ejaculated Mr Gilbert Emborough, who had entered the room in time to hear the last part of this speech. “Nothing could be a bore when she is there!”

“Come, this is most promising!” said Desford. “Who is this glorious she? Am I acquainted with her?”

“No, you ain’t acquainted with her,” replied Gilbert, “but you have seen her! What’s more, you were much struck—well, anyone would be!—and you asked Ned who she was.”

“What, the ravishing girl I saw at the races?” exclaimed Desford. “My dear aunt, of course I will go with you to this ball! The most exquisite piece of nature I’ve seen in a twelve-month! I hoped Ned might present me to her, and very unhandsome I thought it of him that he didn’t do so.”

Gilbert gave a crack of laughter. “Afraid you’d cut him out! See if I don’t roast him for it!”

“But who is she?” demanded the Viscount. “I didn’t properly hear what Ned said, when I asked him that question, for at that moment we were joined by some friends of his, and by the time we had parted from them the next race was about to start, and I thought no more about the Beauty.”

“Shame!” said his cousin, grinning at him.

“Her name is Lucasta,” said Lady Emborough. “She’s the eldest daughter of Sir Thomas Bugle: he has five of ‘em, and four sons. Certainly a very handsome girl, and I daresay she may make a good marriage, for she has all the men in raptures. But if her portion is above five thousand pounds I shall own myself astonished. Sir Thomas’s fortune is no more than genteel, and he hasn’t the least notion of trying to sconce the reckoning.”

“Poor Lucasta!” said the Viscount lightly.

“You may well say so! Her mama brought her out in the spring, and there was never anything so unfortunate! Would you believe it?—within three days of her being presented at Court Sir Thomas received an express letter from Dr Cromer, informing him that old Lady Bugle had been suddenly taken ill! So, of course, they were obliged to post home in a great hurry, because she was very old, and even though one knew she was as tough as whitleather there is always the chance that such persons will be perfectly stout one day, and dead the next. Not that she did die the next day: she lasted for more than two months, which naturally made it impossible for her mama to take Lucasta to balls and assemblies until they are out of black gloves. This dance Lady Bugle has got up is to be quite a small affair. She gives it in honour of Stonor Bugle’s engagement to the elder Miss Windle. A good enough girl in her way, but it’s not an alliance I should welcome for one of my sons!”

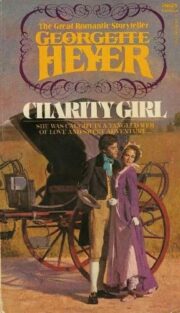

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.