“Well, it may be shocking, but I don’t scruple to tell you that I was even more glad to learn that she wasn’t receiving visitors!” said the Viscount candidly. “She makes me feel I’m sort of a heartless loose-screw, for she’s got a way of sighing, and smiling sadly and reproachfully at me when I accord her the common decencies of civility.” He drew out his watch, and said: “I must be off, Hetta. I’m on my way to Hazelfield, and my aunt won’t like it if I arrive at midnight.”

Henrietta rose from the seat, and accompanied him towards the house. “Oh, are you going to visit your Aunt Emborough? Pray give her my kind regards!”

“I will,” he promised. “And do you—if Grimshaw should have disclosed my presence here!—say all that is proper to your mama! My compliments, and my—er—regret that I should have paid her a morning visit when she was indisposed!” He bestowed a fraternal hug upon her, kissed her cheek, and said: “Goodbye, my dear! Don’t do anything gooseish, will you?”

“No, and don’t you do anything gooseish either!” she retorted.

“What, under my Aunt Sophronia’s eye? I shouldn’t dare!” he tossed at her over his shoulder, as he strode off towards the stableyard.

Chapter 3

Lady Emborough was Lord Wroxton’s sole surviving sister. In appearance they were much alike, but although persons of nervous disposition thought that the resemblance was very much more than skin-deep they were misled by her loud voice and downright manners. She was certainly inclined to manage the affairs of anyone weak-minded enough to submit to her autocracy, but she was inspired quite as much by a conviction that such persons were incapable of managing their own affairs as by her belief in her own infallibility, and she never bore anyone the least malice for withstanding her. She was thought by some to be odiously overbearing, but not by those who had sought her help in a moment of need. Under her rough manners she had a warm heart, and an inexhaustible store of kindness. Her husband was a quiet man of few words who for the most part allowed her to rule the household as she chose, a circumstance which frequently led the uninitiated to think that he was henpecked. But those more intimately acquainted with her knew that her lord could check her with no more than a look, and an almost imperceptible shake of his head. She took these silent reproofs in perfectly good part, often saying, with a good natured laugh: “Oh, there is Emborough frowning me down, so not another word will I utter on the subject!”

She greeted her nephew characteristically, saying: “So here you are at last, Desford! You’re late—and don’t tell me one of your horses lost a shoe, or you broke a trace, because I shan’t believe any of your farradiddles!”

“Now, don’t bullock poor Des, Mama!” her eldest son, a stalwart young man who bore all the appearance of a country squire, admonished her.

“Much he cares!” she said, laughing heartily.

“Of course I don’t!” Desford said, kissing her hand. “Do you take me for a rabbit-sucker, ma’am? None of my horses lost a shoe, and I did not break a trace, or suffer any accident whatsoever, and if you mean to tell me I’ve kept you waiting for dinner I shan’t, of course, be so disrespectful as to accuse you of telling farradiddles, but I shall think it! The thing was I called at Inglehurst on my way, and stayed chatting to Hetta for rather longer than I had intended. She told me to give you her kind regards, by the way.”

“Inglehurst! Why, have you come from Wolversham?” she exclaimed. “I had supposed you to have been in London still! How’s your father?”

“In the gout!”

She gave a snort. “I daresay! And no one but himself to blame! It would do him good to have me living at Wolversham: your mother’s too easy with him!”

The violent altercations which had taken place between Lord Wroxton and his sister when last she had descended upon Wolversham still lived vividly in the Viscount’s memory, and he barely repressed a shudder. Fortunately, he was not obliged to answer his aunt, for she switched abruptly to another subject, and demanded to be told what he meant by instructing his postilions to lodge at the Blue Boar. “I’ll have you know, Desford, I’m not one of these modern hostesses who tell their guests they won’t house any other of their servants than their valets! Such nipcheese ways won’t do for me: shabby-genteel I call ‘em! Your groom and your postboys will be lodged with our own, and I want no argument about it.”

“Very well, ma’am,” said the Viscount obediently, “you shall have none!”

“Now, that’s what I like in you!” said his aunt, regarding him with warm approval. “You never disgust me with flowery commonplaces! By the by, if you were expecting to find the house full of smarts you’ll be disappointed: we have only the Montsales staying here, and young Ross, and his sister. However, I daresay you won’t care for that if you get good sport on the river, which Ned assures me you will. Then there’s racing at Winchester, and—”

She was interrupted by Lord Emborough, who had entered the room in the middle of this speech, and who said humourously: “Don’t overwhelm him with treats you have in store, my love! How do you do, Desford? If you can be dragged away from the trout, you must come and look at my young stock tomorrow and tell me how you like the best yearling I’ve bred yet! He’s out of my mare, Creeping Polly, by Whiffler, and I shall own myself surprised if I haven’t got a winner in him.”

This pronouncement instantly drew the five gentlemen present into an exclusively male conversation, during the course of which Mr Edward Emborough loudly seconded his father’s opinion; Mr Gilbert Emborough, his junior by a year, said that although the colt had great bone and substance he couldn’t rid himself of the conviction that the animal was just a leetle straight-shouldered; Mr Mortimer Redgrave, who had entered the room in Lord Emborough’s wake, and was the elder of that gentleman’s two sons-in-law, said that for his part he never wanted to see a more promising young ‘un; and Mr Christian Emborough, in his first year at Oxford, who had been reverently observing the exquisite cut of his cousin’s coat, said that he would be interested to hear what he thought of the colt, “because Des is much more knowing about horses than Ned and Gil are—even if he doesn’t boast about it!” Having delivered himself of this snub to his seniors, he relapsed into blushful silence. The Viscount, not having seen the colt, volunteered no opinion, but engaged instead in general stable-talk with his host. Lady Emborough allowed the gentlemen to enjoy themselves in their own way for quite a quarter of an hour before intervening, with a reminder to her sons and nephew that if they didn’t rig themselves out for dinner at once they would get nothing but scraps to eat, since she did not mean to wait for them. Upon which the male company dispersed, young Mr Christian Emborough confiding to his cousin, as he went up the broad stairway beside him, that he happened to know that a couple of ducklings and a plump leveret were to form the main dishes for the second course. The Viscount agreed that it would be a shocking thing if these succulent dishes should be spoilt; and young Mr Emborough, taking his courage in his hands, ventured to ask him if he had tied his neckcloth in the style known as the Oriental. To which the Viscount responded gravely: “No, it’s called the Mathematical Tie. Would you like me to teach you how to achieve it?”

“Oh, by Jupiter, wouldn’t I just?” exclaimed Christian, the ready colour flooding his cheeks in gratification.

“Well, I will, then,” promised Desford. “But not just at this moment, if those ducks are not to be overroasted!”

“Oh, no, no! Whenever it is perfectly convenient to you!” Christian stammered.

He then went off to his own bedchamber, more than ever convinced that Des was a bang-up fellow, not by half as top-lofty as his own brothers; and filled with an agreeable vision of stunning these censorious seniors by appearing before them in a neckcloth which they must instantly recognize as being slap up to the mark.

When the Viscount went back to the drawing-room, he found that the party was rather larger than his aunt had led him to expect, for besides the persons she had mentioned, it included Miss Montsale; both the married daughters of the house, with their spouses; a rather nebulous female of uncertain age, in whom he vaguely recognized one of Lady Emborough’s indigent cousins; and the Honourable Rachel Emborough, who was the eldest of the family, and seemed to be destined to fill the roles of universal confidant, companion of her parents, wise and reliable sister of her brothers and sisters, and beloved aunt of their offspring. She had no pretensions to beauty, but her unaffected manners, her cheerfulness, and the kindness that sprang from a warm heart made her a general favourite. And finally, because Lady Emborough had discovered almost at the last moment that her numbers were uneven, the Honourable Clara Emborough had also been included. This damsel, who had not yet attained her seventeenth birthday, was not considered to have emerged from the schoolroom but, as her mama told the Viscount: “It don’t do girls any harm to attend a few parties before one brings ‘em out in the regular way. Teaches ‘em how to go on in Society, and accustoms ‘em to talking to strangers! Of course I wouldn’t let her appear at formal parties until I’ve presented her! And I can depend on Rachel to keep an eye on her!”

The Viscount, who had been watching Rachel check, in the gentlest way, Miss Clara’s mounting exuberance, intervene to give her brothers’ thoughts a fresh direction when an argument which sprang up between them threatened to become acrimonious, and attend unobtrusively to the comfort of the guests, said impulsively: “What a good girl Rachel is, ma’am!”

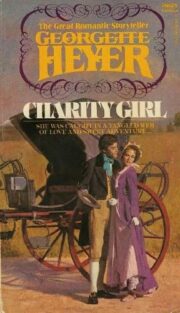

"Charity Girl" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Charity Girl". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Charity Girl" друзьям в соцсетях.