“Is putting your hands behind the head vulgar?”

“Of course. It’s an inviting gesture.”

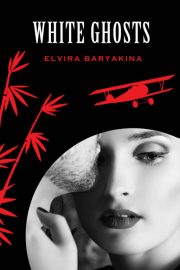

They had disagreements on politics as well. Binbin was convinced that China needed a revolution to sweep away the warlords and the “white ghosts” who funded and protected them.

“You have no idea how it will all end,” Nina said sadly. “Revolutions often start out with good intentions but always end in hunger and tyranny.”

“Don’t you think it’s a tyranny that Chinese people living in their own country are not allowed to go to their own parks?” said Binbin.

They soon realized that it was better not to talk about these things if they didn’t want to end up fighting.

After a lot of hard work, they had a dozen sample calendars ready by November, and the distributors from the Green Lotus Tea House agreed to give them a try. Nina and Binbin were so thrilled that they threw a party for the artists and models.

Shao cautiously tried one of the Russian pies Nina offered him.

“The world has gone mad,” he said. “People have no idea what they are putting into their bodies anymore, and they forget to pray to the spirits of the ancestors. There’s no good can come of it,” he muttered. However, he didn’t a refuse a second pie.

The next day, Nina sent a cable to Canton:

The samples are on their way. Looking forward to seeing the provider to discuss our plans.

But she never got a reply from Klim—neither from this cable, nor the next one she sent.

18. THE DIARY

Daniel returned home, and Edna decided not to reproach him for his affair. They needed to make a fresh start, but things didn’t go quite as she had expected. During the day, Daniel was always in a hurry, and he spent his evenings at the Shanghai Club where women were denied access.

Every day Daniel would insult Edna—not directly with his words but with his coldness and reluctance to spend any time alone with her. She could tell that he no longer felt at home in Shanghai. She could see it in everything he did—the way he talked to servants and the way he couldn’t even remember where his neckties were in his own dressing room. Daniel wasn’t even pretending to “visit Edna”—her house was no more than a temporary shelter for him.

Edna began to lose sleep over her predicament.

It was late. She had already gone to bed, but Daniel had still not returned from the club yet.

She was listening out for the slightest sounds from the street—the sound of a car parking, somebody’s steps echoing along the pavement. Was it Daniel? No, it was only the neighbors.

Edna felt terribly thirsty. She pulled down her nightgown, which had rolled up around her armpits, and headed downstairs into the dining room. The house was as dark and quiet as an old cemetery. The carpets seemed as soft as moss, and the dark silhouettes of the heavy furniture looked like ancient tombstones.

Edna saw a man standing by the window and shrieked.

“It’s me,” Daniel said flatly. “Why aren’t you asleep?”

She approached him and sat on the window sill. A night bird was chirping in the garden. The air smelled of cigarette smoke and damp earth.

Daniel moved into the shade where Edna couldn’t see his face.

“Is there something you wanted to ask?” he said.

“Yes… I need your help,” Edna hurriedly said. “It’s about a bill. My friends and I are trying to impose a ban on child labor, at least within the International Settlement limits. But we’re at a deadlock.”

“What are you talking about?” Daniel said, annoyed.

Edna knew that her words sounded out of place. Should they really discuss bills in the middle of the night? But what else could she say to her husband? Since his return home, they’d had little to talk about.

Daniel made a step towards the door, and she was afraid that he was going to leave.

“Did you know,” Edna said, “that the owners of the silk mills make little girls pull the silk cocoons out of boiling water? These children have permanently scalded hands. The Moral Welfare League has initiated a bill prohibiting child labor, but the Chinese unions threaten to go on strike if our bill passes. It seems they don’t want to do anything to better the lot of their own children.”

Daniel took the matchbox from the mantelpiece and lit his cigarette. The orange flame illuminated his tired face for a few seconds.

“Did you know that these kids are often the only breadwinners in their large families?” he said. “Their parents frequently can’t find work, so if you discharge the children tomorrow, they and their parents will starve to death.”

Edna was taken aback. “And what’s your suggestion? Leave things as they are? Let the children continue to be scalded with boiling water? Let them breathe in cotton dust in the factory shops? They don’t play, they don’t go to school, and if they die, other kids will immediately be sent from nearby villages to take their places. They don’t have a single chance in life!”

“If you want these poor children to have a chance, you will have to create a society where their parents will be able to provide for them,” Daniel said, sighing. “What kind of schooling are you talking about, for goodness sake? Here, in China, even adults have the most primitive education. Their most advanced idea is to take money away from the rich.”

“Precisely!” Edna exclaimed. “If you do nothing, the poor will turn into communists. Our librarian, Ada, has a friend who lives in Canton. He sent her a letter in which he described how he lived among the Bolsheviks—”

“What’s his name?” Daniel’s voice sounded so strange that Edna got scared.

“I don’t know. You should ask Ada. Why?”

Daniel threw his half-smoked cigarette into the fireplace and took Edna’s hand. “Let’s go to sleep. It’s too late to be discussing such things,” he said tenderly.

Edna looked at him, perplexed. A minute ago, he had been so distant and patronizing, and now suddenly everything had changed. He walked Edna to her bedroom and even kissed her goodnight.

He still loves me, she thought. He’s just tired and needs some rest.

Betty met Ada in the street and invited her to have a cup of hot chocolate in the café.

She took one look at Ada and demanded, “What’s up? You look worried.”

Ada admitted that Klim had left the House of Hope, and she could no longer afford to pay for her two-bedroom apartment. Time had passed, and the landlord had told her that he might have to start taking her household items to cover her debt.

In order to get Mrs. Bernard to increase her wages, Ada had suggested getting an aquarium. “I could take care of it for you,” she had ventured. But Edna had no interest in aquariums or anything else for that matter. Her relationship with Mr. Bernard was going nowhere, and the gossip among the house servants was that most likely, he would get himself a mistress again.

Listening to Ada, Betty laughed and then said in a serious tone, “If that Mr. Bernard is such a womanizer, you should seduce him. Then he’ll give you a raise and maybe some valuable presents as well.”

Betty’s idea had impressed Ada so much that from that moment on she could think of little else.

A couple of weeks previously, she had received a parcel from Canton with a sealed package inside it—Klim had asked Ada to pass it on to Nina. But Ada was in no mood to comply with his request. She missed Klim desperately. She had been so worried about him, and all he had written to her were a couple of lines ordering her to act as his messenger girl.

Ada didn’t know how she came to open someone else’s mail. She was just curious to know what Klim had sent to his wife.

Inside there was his diary, and when Ada started to read it, it reduced her to tears. Klim called her “an extra worry” and “an angry teenager.”

Oh, it would be wonderful if Mr. Bernard were to fall in love with Ada. Then she would be able to thumb her nose at Klim and his precious wife. Nina would probably turn green with envy, learning that Mr. Bernard had forgotten about her because of his beguiling and lovely young librarian.

Of course, Ada didn’t want to hurt Edna’s feelings, but it was not as if the Bernards had a happy marriage anyway. It was much better that at least two out of three unhappy people find love.

Daniel Bernard was working for German military intelligence, and he had been greatly relieved when his Berlin command had ordered him to move to the hustle and bustle of Canton, away from the increasingly irritating Edna—and some other unexpected complications.

He had never considered returning to Shanghai, but his major supplier, Don Fernando, had been seriously wounded in Xiguan when the shells the Don himself had brought to Canton started pouring out of the sky. The surgeon said that Fernando would have to spend at least six months in hospital, and Daniel had to go back to Shanghai to re-establish his connections with other smugglers.

Daniel guessed immediately that Ada’s friend from Canton was Klim Rogov. After all, it was he who had introduced her to Edna as a new librarian. Daniel was anxious to find out when Klim had sent his letter to Ada. If it happened after he had met Daniel at the airfield, it could jeopardize his entire operation in Shanghai.

Daniel watched Ada closely for several days and noticed that she had started wearing lipstick. As soon as he would leave his room, she would follow him out from the library and try to attract his attention.

“Mr. Bernard, did you check the new catalog from the bookstore?” Or, “Have you read Edmund Husserl’s works? He wrote Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phe—Phenimore— Oh, now I remember! Ideas Pertaining to a Pure Phenomenology and to a Phenomenological Philosophy. I have a feeling you’ll enjoy it.”

"White Ghosts" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "White Ghosts". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "White Ghosts" друзьям в соцсетях.