Does Edna know what her husband is doing? Klim thought. Probably not. She has lived with this man for years without having any idea who he really is. Nina was fascinated with the scoundrel too, and now because of him, she’ll never know what has become of me.

Finally Klim heard the sound of splashing puddles.

“You son of a bitch!” roared Don Fernando as he appeared in the doorway. “I’m soaked right through to my bones, thanks to you. The things I have to do to save your ungrateful neck… Do you think I have nothing else to do with my time?”

He strode up to Klim, grabbed him by the shirt, and pulled him up on his feet.

“Hey you!” he called to the soldiers. “Let him go.”

His interpreter, a dark-skinned lad dressed in faded army shorts, said something to the soldiers, and they cut the rope on Klim’s wrists.

“Thank you!” said Klim with emotion, rubbing his numb hands together.

Fernando kicked the tin standing on the floor.

“I should put a ball and chain on you and set you to work in the boiler room alongside the Chinese.”

They went outside, and the Don’s bodyguards offered them umbrellas.

“We are going to see Mikhail Borodin now,” said the Don. “He’s been sent from Moscow to be Sun Yat-sen’s chief political adviser. You’ll be doing the interpreting for me, and if you try to escape from me again, I’ll personally break every bone in your body. Is that clear?”

“As clear as day,” Klim nodded. “I owe you for this. Thanks.”

“I gave Mr. Bernard my word that you would never return to Shanghai to spill the beans on him,” the Don said as they got into a motorboat. “We’re going to Vladivostok, my boy. The Bolsheviks want to export their revolution to China, and for us, it’s an excellent opportunity to earn good money by exporting guns and human stupidity.”

That was really bad news. But Klim decided that now was not the time to take issue with Fernando. The first thing he needed to do now was to get away from Daniel Bernard, and as far as possible.

The rain stopped, and a patch of bright blue sky appeared in a gap between the clouds.

“Why the hell did you run away from me in Whampoa?” Don Fernando growled. “I wanted to introduce you to some useful people at Sun Yat-sen’s headquarters. Don’t you realize what a big chance you missed?”

“I’ve spent five years in a civil war,” Klim said. “And I’ve seen enough to last me a lifetime—”

“You were just on the wrong side,” Fernando laughed. “If you had brains, you would have joined the Reds, not the Whites.”

Their motorboat reached the shore, and Klim followed the Don and his bodyguards to the pier.

“Let’s walk,” said Fernando. “Borodin doesn’t live far from here.”

They went up a street flooded with water. There wasn’t a soul around, all the shops were locked, and the windows had been shut tight with wooden shutters.

Klim thought he saw a black shadow flit across one of the roofs. He covered his eyes with his hand to look up and almost tripped over a dead body in the process. Nearby lay three more. The streams of water running along the pavement were red with blood.

“What the—” Don Fernando swore as he slipped on a piece of human gore.

“Boss, we need to get out of here,” said one of the bodyguards, his face turning white.

They rushed into a narrow street with countless advertising panels and reed awnings covering the second-floor windows. Something moved further up the street, and they heard the bark of a machine-gun, its deafening echo reverberating as though they were at the bottom of a well. Shop signs were shattered into splinters, and Klim, Fernando, and the bodyguards tumbled to the ground.

Klim rolled into the gutter and covered his head with his hands. The rainwater flowing over his body riffled the shirt on his back.

The pavement steamed, and here and there the street was lit with golden pillars of light. In the distance, Klim saw soldiers with rifles. Judging from the blood-curdling cries, they were busy stabbing someone with their bayonets.

Fernando groaned loudly. Klim turned his head and saw the Don struggling helplessly in a pool of blood, clutching his thigh. His bodyguards were nowhere to be seen.

“Fernando, keep quiet and play dead,” hissed Klim, but the Don was crazy with pain and was insensible to anything going on around him. His eyes bulged, and he bellowed, breathing heavily.

Every fiber of Klim’s being was clenched into a ball of nerves. They’re going to kill us. I know they will.

He crawled over to Fernando, grasped him under the arms, and dragged him into a niche in the wall where a large gilded statue of the goddess Guan Yin stood. He managed to squeeze the Don into the narrow space between the statue and the wall, but there was nowhere for him to hide.

“Sit here and try not to give yourself away,” Klim whispered to Fernando, but the Don didn’t answer. His eyes rolled back, and foam appeared on his ashen lips.

There was a splash of water and the clatter of wooden shoes. Somebody’s hands pulled Klim out of the niche, and he hit his head on a big stone censer standing in front of Guan Yin. For a brief second a black shadow stood over him, a bayonet covered with blood flashed—and then there was a deafening rumble.

The last thing Klim saw was the face of the goddess Guan Yin moving rapidly towards him. Why is she trying to kiss me? he thought and passed out.

17. THE CHINESE ACTRESS

Despite her enquiries and desperate search for Klim, Nina had never learned what had happened to him that night. One thing was certain: he had got in trouble with the police. Ada had told Nina that they had come to their apartment and searched the place looking for him.

That was it. Now Nina was alone, only with the baby by her side, and no one was there to back her up.

Anxiety and uncertainty were wearing Nina out completely. She was too depressed to do anything, much less start a business. But the bills kept coming, and Nina was forced to think about her situation.

She had noticed an article in a newspaper about a group of Jesuits who were collecting donations for an art school for orphans. According to the article, the monastery orphanage had produced many brilliant artists, and now their works were in demand not only in China but all over Europe.

Nina came up with a crazy idea: What if she were to offer Gu Ya-min’s collection to the Jesuits? Since they were engaged in the arts, they were bound to have connections with art collectors. Sure, the monks might hand Nina over to the police, but on the other hand, the church in China was not particularly famous for its rectitude. Nina had learned from Don Fernando that the monks were ready to trade anything from theater advertising to sausage skins if it meant income for their charitable works. Many of the gambling machines in the bars and restaurants of Shanghai were the property of the mission of Saint Francis de Sales. The Augustinians produced fake perfume, and other orders had no qualms about investing money sent by Mussolini for the promotion of the Italian language and the Catholic Church into real estate.

Nina tried to find out everything she could about the Jesuit monastery in the Siccawei district. It had been founded over sixty years before and had gradually become a city within a city. There were colleges, an observatory, a museum, a library, dormitories, hospitals, and several churches. The Jesuits were especially proud of their famous orphanages that took in more than four hundred abandoned babies every month. The mortality rate was very high, but those that survived were given an education and profession. Boys became carpenters or worked in the garden, while girls sewed, embroidered, or took up the fine art of lace-making that had been imported from Europe. Their life was hard but a life nevertheless. And the most gifted children could make a real career for themselves upon graduation from the art school, which was considered the best in China.

Nina went to Siccawei feeling like the bold little mermaid on her way to visit the sea witch. Leaving the car in the shade of a plane tree, she stepped up the hot porch steps with her heavy package under her arm and knocked on the entrance door. A young novice showed her to the office of Father Nicolas, a slender, white-haired monk dressed in a dark robe.

“Make yourself at home, please,” he said in French.

Nina rather felt as if she was in a school headmaster’s office. The room was filled with book cabinets, dusty stuffed animals, and there were maps rolled into tubes standing in the corner.

On her way to the monastery, Nina had decided that she would pretend to be a dispassionate art critic, but when she started telling Father Nicolas about her proposal, she became so embarrassed that she found it hard to look into his eyes.

“May I have a look at the things you’ve brought?” he asked.

Nina unwrapped the heavy bundle on the desk and gave Father Nicolas an intricately-carved piece of mammoth ivory.

He examined it carefully through his magnifying glass. “Do you have an inventory of your collection?”

Nina handed him several sheets of paper. “Yes, I do.”

Without hurrying, he read through the list. Nina waited nervously for him to get to the item entitled “purple amethyst male reproductive organ,” expecting him to send for the police in shock and outrage.

“I’ll have to talk to the brothers,” Father Nicolas said finally. “This is a delicate matter, but if the rest of your collection is of the same quality, then I’m sure we’ll be able to come to an agreement.”

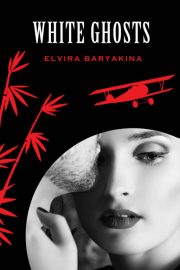

"White Ghosts" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "White Ghosts". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "White Ghosts" друзьям в соцсетях.