We sleep in the open on the upper deck, and I always dream of Nina and Kitty. I wake up suddenly, as if I’ve been given an electric shock, and then watch the night sky through the gaps between the bales and crates. There are so many stars up there that it seems as if a huge luminescent deluge has been suspended in time and space over our little planet. At the moment these dreams and optical illusions are the only things that prevent me from plunging into oblivion myself.

As we passed Formosa Island, our ship caught the tail end of a typhoon. Every forty seconds a wave would hurl us down into the boiling abyss, the bulkheads were at breaking point, and a permanent foam danced over the greenish waves like a crowd of sea demons.

I don’t even know how we managed to limp into Hong Kong—our junk was on its last legs. With such a sensitive cargo onboard, there was no way that we could just roll up to the docks. So we spent what seemed like an eternity stuck out at sea, waiting for Don Fernando to negotiate safe harbor with the right people in the city.

Bored and with nothing to do, I would spend hours observing everything around me through binoculars: the sea dotted with countless small islets, outcrops of rock covered with dense vegetation, and a string of ships waiting in line to be unloaded. The heat was so stifling that the air felt as if it had thickened into hot jelly. The humidity not only soaked into my clothes but through every fiber of my being.

I desperately wanted to go ashore to send Nina a cable, but the Don wouldn’t stand for it. He was afraid that I’d spill the beans about his cargo, and customs would arrest the Santa Maria. He ordered his men to confiscate my money, including the not inconsiderable sum I had won from him at cards, so I wouldn’t hire a boatman and sneak away. I should have known the old crook would double-cross me.

Finally, the junk was repaired, but Fernando was in no hurry to set sail. He’d heard that the Cantonese merchants were at complete loggerheads with Sun Yat-sen. He is convinced that the political temperature will soon rise around here and with it the price for illicit arms and ammunition.

We only got underway when the Soviet steamer, the Vorovskoy, entered the harbor. Like the Don, the Bolsheviks smuggle arms to Sun Yat-sen. Their documents claim that they’re shipping an exceptionally large load of pianos, but in reality, the oversized crates and packaging contain machine guns and ammunition.

The Don decided that we need to get to Canton before our competitors, and so we sailed up the Pearl River, our Mexican flag fluttering gaily from our stern.

I had assumed that Southern China is a jungle kingdom but it’s nothing of the sort. The forests along the coastline have long been cut down, and the land has been turned into uniformly square rice paddies. Flocks of birds fly over the patches of reeds. Sharp-horned buffalo watch indifferently as our junk sails by, small boys astride their humped backs, which protrude out of the water like semi-submerged rocks.

On our way to Canton, the Santa Maria dropped anchor at the island of Whampoa, the site of Sun Yat-sen’s military training camp.

After long negotiations in Cantonese, of which I don’t understand a word, we were finally allowed to go ashore.

“I have to talk to some Russians,” Don Fernando said. “You’ll be my interpreter.”

I told him I wasn’t going anywhere until he gave me my money back, and reluctantly the Don counted out one hundred Hong Kong dollars. “I ought to shove it down your throat, you stubborn old goat,” he said. “I’m beginning to regret saving your worthless ass from Wyer.”

Don Fernando had already visited Whampoa Island, and he confidently led me through the training ground packed with obstacle courses and dark-skinned cadets. They couldn’t have been more than fifteen or sixteen years old and resembled a jamboree of innocent boy scouts in their short trousers, short-sleeved shirts, sandals, and red neck scarves.

I couldn’t believe that these kids were about to be sent into battle. However, it’s a well-known fact that teenagers make the most dedicated and unquestioning soldiers. A world-weary, experienced men would never rush to die for the sake of someone else’s ideas, while an idealistic teenager can easily be convinced to sacrifice his life to change the world.

Their military instructors are the Red Army and German officers. They teach their cadets how to march in formation and shoot at straw dummies, and the political instructors fill the boys’ heads with a heady cocktail of Marxism, nationalism, and half-baked patriotism—a perfect and explosive recipe to transform semi-literate young men into fanatical cannon fodder.

We had arrived at the island at the ideal moment. After another fight with the Chamber of Commerce, Sun Yat-sen had moved to Whampoa and was preparing his counter-offensive. The head of his military academy, Chiang Kai-shek, had learned that Fernando had brought weapons and summoned him urgently, and I stayed waiting for the Don in the shade of a banana tree. It was there that I met a young man by the name of Nazar, who had come from Moscow in order to complete an internship at the English-language Bolshevik newspaper, the People’s Tribune.

Nazar is nineteen years old, fair-haired, rosy-cheeked, and as full of youthful energy as a spring lamb. I told him that I work for the Daily News, and for some reason, Nazar assumed it was a Soviet newspaper.

“We are so lucky to be here,” he enthused. “Canton is now the main arena of our struggle against global capitalism.”

When he told me that he was about to get a motorboat into the city, where he lives, I realized I wasn’t going to get a better chance to escape from Don Fernando. I casually asked Nazar if he could take me with him, saying that I needed to find a telegraph office to send a cable to my wife. He agreed.

Canton was astonishing—but not in any positive sense of the word. From a distance, its slums are as unremarkable as anywhere else in the world. But it’s only on closer inspection that you realize that this sprawling mass of planks, rags, and rubbish is floating on water, with boats filling the numerous canals and backwaters as far as the eye can see. I had seen people living on sampans in Shanghai before, but nothing quite on the phenomenal scale of Canton’s floating neighborhoods. According to Nazar, this place is home to about two hundred thousand people. They use the river to wash their clothes, quench their thirst, and as a final resting place for their dead, even those who have succumbed to infectious diseases.

Nazar took me to Shamian Island where the foreign concessions and the telegraph office are located. However, we were met by a patrol as soon as we approached the landing stage. I tried to hail them but was given very short shrift when they heard my accent. “Are you Russian? Don’t even think of landing or we’ll open fire.” Shamian Island is on total security lockdown following recent developments in the city, and anyone speaking with a Russian or German accent is treated as an enemy.

It was too late to look for another telegraph office, and since I had nowhere to go, Nazar invited me to stay the night in his Soviet dormitory.

We ended up taking a couple of palanquins. Nazar apologized profusely for this exploitative, imperialist mode of transport, but the sun had already set, and it was unsafe to walk Canton’s streets at night. The locals here hate “white ghosts” so much that the Russians and the Germans have to wear an armband with a special insignia indicating that we are “friendly.” These work quite well during the day but are no good after dark.

Nazar and I got into the carved booths, the porters then picked us up and ran, their wooden sandals clattering against the pavement.

Canton’s streets are so narrow that in some places I could have stretched arms through the palanquin’s open windows and touched both walls. I had a feeling that we were traveling through a catacomb and that there was no way out.

Finally, we reached a three-story building with a balustrade, located in a quiet street. This was the Soviet dormitory.

Nazar lives in a room furnished only with a portrait of Lenin, a painted Chinese cabinet, and floor mats with blue porcelain bricks, which the locals use instead of pillows. Supposedly, they’re pleasantly cool to the touch when you rest your head on them.

The bathtub also made a big impression; it was a clay vat, half my height, but so narrow that you can only wash while standing.

Nazar gave me a piece of black sticky soap and a bottle of Lysol, the surest precaution against parasites.

“Put at least a tablespoon into the water,” he said, “or you’ll end up with scabies or maybe something even worse.”

When I returned to his room, it was full of foul smelling, suffocating smoke, which emanated from a glowing cord twisted like a snake in a clay saucer.

“This is to keep the mosquitoes away,” Nazar said. He had come equipped with a mosquito net but had put it in the closet before leaving for Whampoa Island, and now after a couple of days, it was covered with black mold. Neither Nazar nor I dared to touch it. Goodness knows what kind of pests it contained now.

We stretched out on our floor mats, and Nazar told me about the life and customs of the Soviet commune.

He seems to have two completely contradictory personalities that coexist within him simultaneously. One is a very sensible, intelligent young man who appreciates the benefits of civilization, the division of labor, and personal comfort. He is perfectly happy with the fact that the Soviets employ maids to clean the dorm rooms and do the laundry. He doesn’t consider this to be exploitation of the working people in the slightest.

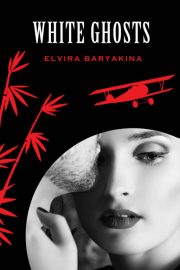

"White Ghosts" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "White Ghosts". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "White Ghosts" друзьям в соцсетях.