I rather spitefully told Ada that she was just being jealous. “Did you want me to adopt you instead? But how could I adopt a girl who is constantly throwing herself at me?”

My not very subtle hint made Ada spit blood, and she started cursing at me, employing the entire range of choice language she had picked up while working as a taxi-girl.

Ada knows absolutely nothing about little children. Kitty has turned into a lovely baby. She has a round face, eyes as black as currants, a cute little nose, and eyebrows that look like little clouds. Not long ago, her first two bottom teeth came through, and she tries them on everything she can sink them into—from her own feet to a utility bill Nina had absentmindedly left on a chair.

It seems strange now to think that I could ever have been bothered that she isn’t my flesh and blood. Who cares? Kitty radiates happiness the same way as a light bulb radiates light, and she always makes me laugh. She is a bundle of joy—and that is the best description I can find for my daughter.

Nina has fallen for Kitty’s charm too, even though there was a time when just looking at our baby girl made her feel sick to the heart. Now Nina sings her lullabies, patiently spoons porridge into her, and talks to her in a hilarious way: “Who is this little girl? And where has she been today? Has she been with Mommy to hire some men to move the furniture around the house?”

Kitty stares at Nina wide-eyed and appears to understand her questions perfectly, answering them with a loud “Ah-ah-ah.” The performance is so amusing that even the servants come into the room to watch.

While Nina and I have fallen in love with Kitty with surprising rapidity, our own relationship is nothing like as rosy. It’s as if we are living in a movie: everything is black and white, and the actors have such a thick layer of makeup on their faces that their attempts to communicate with each other are reduced to the farcical and grotesque. The plot of our movie is also in black and white, and lacking in subtlety—the sort of primitive Western that the residents of Shanghai go mad for. The Fair Lady has been abused and is in distress, and the Lone Cowboy has sworn to avenge her no matter the cost. Don’t ask me what good this vengeance could possibly do him or the Fair Lady; he has no idea himself. But his natural sense of justice won’t allow him to tolerate the Sheriff’s brazen actions. The villain must be punished.

Captain Wyer is a British citizen with all the benefits that his powerful imperial state can bestow on him. I have no official status whatsoever; I can barely stick my head over the parapet let alone demand justice. The only redress I can find is through spiteful articles that I publish as a freelancer in a Chinese student newspaper, which is happy to accept anything publicizing the corruption of local white officials. Nina told me that I ruin everything I touch, so now I’m going to try this theory out on Captain Wyer’s reputation.

I have become a great expert on his life story. It turns out that as a young man Wyer was shanghaied out of his home city of London and brought to China. In those days, very few people went voluntarily because of the fear of fatal oriental diseases, so the merchant ships were often reduced to abducting unsuspecting young men in the ports. Once they were out at sea the poor wretch could complain as much as he liked, but no one was going to listen to him.

When the young Wyer arrived in Shanghai he jumped ship and joined the local self-defense unit, which later became the International Settlement’s police force. At first, he sold opium himself but then he found he could make more money by taking bribes from the dealers. As he moved up the ranks of the new force, he was quick to learn the manners of his superiors and, like many other newly arrived adventurers, invented a socially acceptable past that had him adopted into the local elite. When opium was banned, he realized there were fantastic amounts of money to be made by fighting a phony war against the drug.

I still can’t figure out the way this man’s mind works and why he is trying so hard to soil his own nest. Even if he doesn’t care about the city he is living in and his ultimate plan is to retire to a life of luxury back home in London, he must surely understand that his daughter has no plans to abandon Shanghai and that she would be left living in a city of drug addicts, gangsters, and corrupt officials of his own making.

I don’t need to look hard to find material to ruin Captain Wyer’s reputation with the Chinese. A simple translation of the speeches he openly gives at the banquets in his gentlemen’s club is more than sufficient.

“Imperialism brings the backward peoples modern science, and the teaching of Christ,” he says. “We have no choice but to use force against the Chinese because they are not willing to give up their ignorance and lack of hygiene. Why is a Chinese life worth no more than a couple coppers? Because that is its true price. A coolie has no valuable skills, and he is easy to replace. If he dies, no one will mourn his departure. Indeed, the people he shares his quarters with are only too grateful to have the extra space.”

The student newspapers don’t have a very large circulation, but each issue is stuck to public walls and fences and read by a large number of people. The students use a special varnish, which sticks the newspaper firmly onto board or wall masonry, and it’s not easy to remove it. The authorities try to paint over these seditious articles, but within a couple of hours, a new sheet appears on a different wall around the corner.

Wyer knows that the Chinese harass him in the press, but he can’t do anything about it. The entire local population hates him, including the policemen who work under him and carry out his orders. Unsurprisingly, they aren’t exactly busting a gut to defend his “good name” either.

The irony is that Wyer himself has had a big hand in creating a society where any problem can be solved with a bribe. If he closes down one objectionable newspaper, it will only reappear a week later under a new title. The students have the money for it—partly from local patriotic merchants and partly from the Soviet government which hopes to shatter the corrupt colonial system.

Ten years from now, I’ll be telling my children amazing stories about how I and the Bolsheviks worked together to kick the Police Commissioner out of Shanghai.

Although it’s painfully presumptuous to talk about children in the plural at the moment. Children are hard to come by if, according to the script, the Lone Cowboy is not even allowed to kiss the Fair Lady. Like the films on show in the Shanghai cinemas, all content of the remotest sexual nature is censored out of our movie and there’s little chance of it ever being restored.

The deeper I dig into Wyer’s case, the more grisly the details that come to light.

He has created a small slave state in the International Settlement’s prison. Every prisoner has a job to do: some weave straw mats, some sew uniforms for the police, and some carve tombstones.

The lower ranking guards earn good money supplying the inmates with opium, tobacco, food, and letters from home. The officers get even more in bribes from the inmates to avoid heavy labor and to arrange visits from wives or prostitutes. But the biggest money is made by the firms owned by Captain Wyer, which use the free labor provided by the prisoners to fulfill big contracts.

I was told that there is a pond behind the prison where the convicts wash the dirty tablecloths from restaurants. When I went to investigate, it turned out that they were being guarded by none other than Felix Rodionov.

He was sitting under a tree, watching the prisoners chained to each other, crouching on a jetty, green with slime, while beating wet tablecloths with laundry paddles. It was an eerie sight—all those unkempt heads with their matted hair, sweaty backs, protruding ribs, and gray, cracked heels.

Felix was delighted to see me. He told me that last winter Wyer had seconded him to Hong Kong to learn from the local police there, but when Felix came back, he had been transferred to the prison staff. This certainly wasn’t the sort of “promotion” he had been expecting, but he wasn’t in a position to argue with Wyer. As an immigrant, Felix was grateful to have any job, no matter what it was.

I told him that I wanted to write an article about the prison system, and he provided me with a story of a Chinese woodcarver who makes decoy ducks that are almost indistinguishable from the real birds. The man has spent two years waiting for his case to be heard. He has no relatives to intercede for him, and he is illiterate and can’t write a petition for himself. When the committee from the Municipal Council visits his cell, he tries to attract attention to himself, but the translator from the prison administration won’t translate anything that might cast a shadow on his bosses. Captain Wyer loves duck hunting and has no intentions of parting with his woodcarver. He has ordered that the man should be kept detained for an unlimited period, but not hurt.

My article is translated and published in the Chinese student newspaper. I hope it’ll engender wide public outrage, and the poor woodcarver will be rescued by his fellow countrymen.

Felix sent me a note: “Come. It’s urgent.” I thought he had a new story for me and rushed to meet him at his pond. But what he had to say exceeded all my expectations.

“Today our senior warden got drunk and blurted out to me that Jiří Labuda was strangled on Wyer’s orders. I think that our ‘Czechoslovak Consul’ was planning to spill the beans on the wrong people and that was why he was sent to meet his maker.”

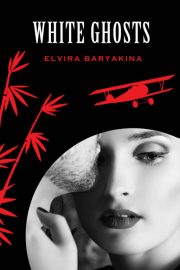

"White Ghosts" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "White Ghosts". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "White Ghosts" друзьям в соцсетях.