They stared at each other, then looked away and said no more.

They planned it carefully. Sofia would follow the railway track, travel by night and hide up in the forest by day. It was safer that way and meant she wouldn’t suffer from the cold overnight because she’d be walking. It was March now and the temperatures were rising each day, the snow and ice melting, the floor of the pine forests turning into a soft damp carpet of needles. She should travel fast.

‘You must head for the River Ob,’ Anna urged her, ‘and once you’ve found it, follow it south. But even on foot and in the dark, travelling will be hard without identity papers.’

‘I’ll manage.’

Anna said nothing more. The likelihood of Sofia getting even as far as the River Ob was almost nil. Nevertheless they continued with their preparations and took to stealing, not only from the guards but also from other prisoners. They stole matches and string and pins for fish-hooks and a pair of extra leggings. They wanted to snatch a knife from the kitchens but nothing went right despite several attempts, and by the eve of the day planned for the escape, they still had no blade for Sofia. But Anna made one last foray.

‘Look,’ she said as she came into the barrack hut, her scarf wound tight over her chin.

She hunched down beside Sofia in their usual place on the wooden floor, backs to the wall near the door where the air was cleaner, to avoid the kerosene fumes that always set off Anna’s coughing spasms. From under a protective fold of her jacket she drew her final haul: a sharp-edged skinning knife, a small tin of tushonka, stewed beef, two thick slices of black bread and a pair of half decent canvas gloves.

Sofia’s eyes widened.

‘I stole them,’ Anna said. ‘Don’t worry, I paid nothing for them.’

They both knew what she meant.

‘Anna, you shouldn’t have. If a guard had caught you, you’d be shot and I don’t want you dead.’

‘I don’t want you dead either.’

Both spoke coolly, an edge to their voices. That’s how it was between them now, cool and practical. Sofia took the items from Anna’s cold hands and tucked them away in the secret pocket they had stitched inside her padded jacket.

‘Spasibo.’

For a while they didn’t speak because there was nothing left to say that hadn’t been said. Anna coughed into her scarf, wiped her mouth, leaned her head back against the wall and concentrated on the spot where their shoulders touched. It was the only place of warmth between them now and she cherished it.

‘I’m fearful for you, Sofia.’

‘Don’t be.’

‘Fear is a such filthy stain rotting the heart out of this country, like it’s rotting my lungs.’ Anna struggled for breath. For a while they said nothing more but the silence hurt, so Anna asked, ‘Where will you go?’

‘I’ll do as you say and follow the River Ob, then head west to Sverdlovsk and the Ural Mountains. To Tivil.’

That came as a shock. ‘Why Tivil?’

‘Because Vasily is there.’

Anna felt the sick hand of jealousy squeeze her guts.

‘Are you all right, Anna?’

Sofia’s eyes were gazing at her with concern, and that’s when the red haze hit. It made her want to strike out, to shout and scream Nyet! into that sweetly anxious face. How dare Sofia go to Tivil? Anna thrust her hands tight between her knees and clamped them there.

‘Vasily?’

‘Yes, I want to find him.’

‘Is he the reason you’re escaping?’

‘Yes.’

‘I see.’

‘No, you don’t.’

But she did. Anna saw only too well. Sofia wanted Vasily for herself.

Sofia looked at Anna intently and then sighed. ‘Listen to me, you idiot. You said that Maria, your governess, told you about Svetlana Dyuzheyeva’s jewellery.’

Anna frowned. ‘Yes. Vasily’s mother had beautiful jewels.’

‘She told you,’ Sofia continued slowly, as though speaking to a child, ‘that Vasily said his father had buried some of the jewels in their garden at the start of 1917, for fear of what might happen.’

‘Yes.’

‘And that, after the Civil War, Vasily went back for them and later hid them in the church in Tivil.’

‘So it’s just the jewels you’re going for.’

‘No, not just the jewels.’

‘Vasily too?’

‘Yes, for Vasily too.’

Anna shuddered. She couldn’t stop it, a cold spiky tremor that crept through her bones. Again she said, ‘I see.’

Sofia’s shoulder gave a little shove that took Anna by surprise and started her coughing again. She hunched over her scarf, pressing it to her mouth, fighting for breath. When it was over, she looked flat-eyed at Sofia.

‘Take good care of him,’ she whispered.

Sofia tilted her head to one side. For a while she said nothing, then she reached out and pulled back the scarf from Anna’s mouth. In silence they both studied the blood stains on the cloth. Sofia spoke very clearly and deliberately.

‘There’s only one reason I’m leaving here. Using the jewels and with Vasily’s help, I will come back.’

‘Why in God’s name would you want to return to this stink-hole? ’

‘To fetch you.’

Three words, only three. But they changed Anna’s world.

‘You won’t survive another winter here,’ Sofia said quietly. ‘You know you won’t, but you’re too weak to walk hundreds of miles through this bloody taiga, even if you could escape. If I don’t go to fetch help for you, you’ll die.’

Anna couldn’t look at Sofia. She turned her head away and fought the onrush of tears. She felt the sickening weight of fear and knew it would be there inside her for every second that Sofia was gone.

‘Sofia,’ she said in a voice that she barely recognised, ‘don’t get yourself eaten by a wolf.’

Sofia laughed. ‘A wolf wouldn’t stand a chance.’

5

The Ural Mountains July 1933

The dog. That’s what Sofia heard first. The dog. Then the men.

The sound of them carried to her through the quivering breath of the forest as the hound’s paws splashed through a gulley and scrabbled up the other side. Coming closer, too close, with belly-deep whines, teeth bared and tongue loose, thirsting for the taste of blood. It set Sofia’s own hackles rising into sharp spikes of fury. Her hand reached out, her scarred fingertips clutching at the air in front of her as if for one last second she could capture its placid warmth and cradle it to her chest.

But how could she be angry with a dog? The animal was only doing what it did best, what it was bred to do. To track its prey.

And she was its prey. So they’d come for her at last. She shivered.

Had they come by accident? Or design?

It didn’t matter. She was prepared.

Sofia had been watching the evening sun slide away from her along the curving line of the trees, transforming the greens to amber and then to a fierce painful red. A komar landed on her bare arm. She didn’t move, but watched the insect’s tiny body turn into a ruby tear as it drank its fill of her blood. It made her think of the way the labour camp had tried to suck the lifeblood out of her. She struck hard and the mosquito was transformed into no more than a pink smear on her skin.

She was standing in the doorway of a cabin. She’d found it in a small clearing that was hidden way up on the northern slope of the forest, deep in the Ural Mountains. It wasn’t really a clearing, but more a ragged scar where lightning had decapitated a tall birch which, as it had fallen, had brought down a handful of young pine trees. The cabin was skilfully built to withstand the merciless Ural winters, but now it was old and patched with moss, tilting to the right like an old man with cramp.

It looked as if its bones ached just the way hers did. It had taken four never-ending, hard, grinding months as a fugitive to reach this point. She’d scuttled and scrambled and fought her way halfway across Russia, travelling always south-west by the stars. The odd thing was that it had taken her a long time – far too long – to get used to being on her own. That had startled her.

The nights were the worst. So big and empty. Five years of sleeping packed five to a bed board and you’d think she’d relish the sudden relief of solitary living, but no. She could hardly bear to be on her own at first because the space around her was too huge. She found sleep hard, but gradually her mind and her body adapted. Then she travelled faster.

The actual escape from Davinsky had proved even more dangerous than she’d expected. It was a dull damp day in March with a lingering mist that swirled among the trees like the dead drifting from trunk to trunk. Visibility was poor. A perfect day to join the ghosts.

She and Anna had planned it carefully.

They waited until the perekur, the smoke-break, which gave her five minutes. Five minutes was all. Sofia stood in a huddle with the other women from her brigade and saw Anna watching her, taking in every last detail, saying nothing. The idea of leaving Anna behind felt absurdly like treachery, but she had no choice. Even alone her own chances of survival were… She stopped her thoughts right there. Minute by minute, that’s how she would survive. Adrenalin was pumping through her veins and her throat felt dry.

She stepped closer to Anna and said quietly, ‘I promise I’ll come back for you. Anna, wait for me.’

Anna nodded to her. That’s all. Just a nod and the look that passed between them. A moment frozen in time with no beginning and no end. A nod. A look. Then Anna left the huddle of women and hurried over to where four guards were standing around a brazier and smoking, stamping their feet and laughing at each other’s crude jokes. One guard was holding a dog on a chain, a German Shepherd that lay like a black shadow on a patch of icy grass, its eyes narrow slits.

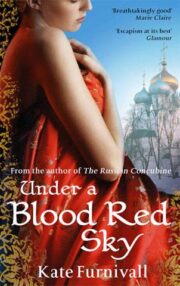

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.