Anna skirted the dog warily. She was to create the distraction, so with a shriek of alarm she started to make a fuss, waving her arms about to draw attention.

‘Look!’ she shouted. Heads turned towards her. ‘Look there!’ she shouted again, this time pointing urgently at the line of pine trees behind the guards.

A ribbon of space had been hacked out of the forest for the new road they were building, but beyond that lay a dense and gloomy world where little light penetrated. There, power was wielded by claws and teeth instead of guns.

‘What?’ All three guards jumped and swung round, raising their rifles.

‘Wolves!’ she warned.

‘Fuck!’ exclaimed one of the men. ‘How many?’

‘Tri. Three. I saw three,’ Anna lied. ‘It could have been more.’

‘Where?’

A second guard came forward. ‘I can’t spot any.’

‘There’s one!’ Anna screamed. ‘Over there. See that pale shape behind…’ her voice was rising in panic, ‘no, it’s moved, but I saw it, I swear I did.’

A rifle shot rang out. Just in case. The dog and its handler were running closer to the trees. The prisoners all watched nervously. Sofia seized the moment: everyone’s attention was focused on the forest to the north of the road, so to the south she turned and began to move. The trees were fifteen metres away. Her heart was hammering in her chest. Don’t hurry, walk slowly. She cursed the ice that crunched noisily under her boots. Ten metres now, and she could see the tall slender trunks coming closer.

‘There!’ Sofia heard Anna cry out again. ‘Quick, off to your right – look, one of the wolves is over that way!’

The guard dog was whining as it strained at its leash, but she heard the handler utter a single word of command and the animal dropped to the ground in silence. The hairs on the back of Sofia’s neck rose and she didn’t dare breathe. Six metres now between her and the beckoning darkness of the forest, that was all. So close she could taste it. She made herself keep to a steady walk and resisted the urge to look behind her.

Another rifle shot rang out in the still air and Sofia instinctively ducked, but it wasn’t aimed at her. It was followed by a string of bullets that ripped through the undergrowth on the north side of the road, but no howls lifted into the mist.

‘That’ll scare the shit out of the creatures,’ one guard declared with satisfaction and lit himself a cigarette.

‘OK, davay, back to work, you lazy scum.’

There was a murmur of voices, and quickly Sofia lengthened her stride. Three more steps and-

‘Stop right there.’

Sofia stopped.

‘Where the hell do you think you’re sneaking off to?’

Sofia turned. Thank God it wasn’t one of the guards. It was the leader of one of the other brigades, a woman with hard eyes and even harder fists. Sofia breathed again.

‘I’m just going to the latrine pit, Olga.’

‘Get back to your work or I’ll call a guard.’

‘Leave it, Olga, I’m desperate to-’

‘Don’t fuck around, we both know the nearest latrine is in the opposite direction.’

‘That one’s overflowing, too disgusting to use, so I-’

‘Did a guard give you permission?’

Sofia sighed. ‘Are you blind, Olga? Of course not, they’re all busy watching out for the wolves.’

‘You know the rules. You can’t leave your work post without permission from a guard.’ The woman’s mouth clamped shut with an audible snap of her false teeth.

‘What’s it to you, anyway?’

‘I am a Brigade Leader. I make sure the rules are obeyed. That,’ she said with satisfaction, ‘is why I have bigger food rations and a better bed than you do. So-’

‘Look, I really am desperate, so please just this once-’

‘Guard!’

‘Olga, no.’

‘Guard! This prisoner is running away.’

The ground was still packed tight with the last of the winter ice. Every thrust of the spade made Sofia’s bones crunch against each other and she muttered under her breath at the guard, a thick-set man who stood watching her with a rifle draped over his arm and a grin let loose on his face.

She had been ordered to dig out a new latrine pit as punishment and it was like digging into iron, so it took her the rest of that day. It could have been worse, that’s what she kept telling herself. It could have been much worse. This punishment was for not requesting permission before stepping away from the road because, thankfully, none of the guards believed the Brigade Leader’s story that she had been trying to escape. The punishment for an escape attempt? A bullet in the brain.

Damn it though. Sofia cursed her luck for running into Olga. She’d been so close. She’d snatched a brief glimpse of the freedom out there in the deepening shadows of the forest.

The latrine, which had to be three metres long and one metre deep, was set no more than two paces beyond the edge of the trees. The pines there were sparse and offered only token privacy. Near the end of the day, when the mists were stealing the branches from the trees, a young dark-haired girl was made to come and help her as punishment for swearing at a guard. As they worked side by side, in silence except for the metal ring of spades, Sofia attempted to catch sight of Anna on the road, but already her brigade had moved on, so she was left alone with only the girl and the guard.

Oddly, she didn’t feel sick with disappointment at her failure, even though she knew she had let both Anna and herself down badly. It was as if she was certain in that strange clear space inside her head that her brush with freedom was not yet over. So when the actual moment came, she was expecting it and didn’t hesitate.

The sky was beginning to darken and the rustlings on the forest floor were growing louder, when the girl suddenly pulled down her knickers, straddled the new latrine pit they’d dug and promptly christened it. The guard’s grin widened and he ambled over to watch the steam rise from the yellow trickle between her legs.

That was the moment. Sofia knew it as clearly as she knew her own name. She stepped up behind him in the gloom, raised her spade and slammed its metal blade on to the back of his head.

There was no going back now.

With a muffled grunt, he folded neatly to the ground and slumped with his head and one arm hanging down into the pit. She didn’t wait to find out if he was alive or dead. Before the girl had pulled up her knickers and screamed out in alarm, Sofia was gone.

They came after her with dogs, of course. She knew they would. So she’d stuck to the marshes where, at this time of year, the land was water-logged and it was harder for the hounds to track down her scent. She raced through the boggy wastes with long bounding strides, water spraying out behind her, heart pounding and skin prickling with fear.

Time and again she heard the dogs come close and threw herself down on her back in the stagnant water, her eyes closed tight, only her nose and mouth above the surface. She lay immobile like that for hours in the slime while the guards searched, telling herself it was better to be eaten alive by biting insects than by dogs.

At first she had the stash of food scraps in the secret pockets that Anna had sewn inside her jacket, but they didn’t last long. After that she’d existed on worms and tree bark and thin air. Once she was lucky. She stumbled upon an emaciated moose dying from a broken jaw. She’d used her knife to finish off the poor creature and, for two whole days, she’d remained beside the carcass filling her belly with meat, until a wolf drove her to abandon it.

As she travelled further through the taiga, mile after mile over brittle brown pine needles, seeking out the railway track that would lead her south, at times the loneliness was so bad that she shouted out at the top of her lungs, great whooping yells of sound, just to hear a human voice in the vast wilderness of pine trees. Nothing much lived there, barely any animals other than the occasional lumbering moose or solitary wolf, because there was almost nothing for them to eat. But in some odd kind of way the yelling and the shouting just made her feel worse: the silence that responded only left a hole in the world that she couldn’t fill.

Eventually she found the railway track that she and Anna had talked about, its silver lines snaking into the distance. She followed it day and night, even sleeping beside it because she was afraid of getting lost, till eventually she came to a river. Was this the Ob? How was she to know? She knew the River Ob headed south towards the Ural Mountains but was this it? She felt a wave of panic. She was weak with hunger and couldn’t think straight. The grey coils of water below her appeared horribly inviting.

She lost track of time. How long had she been wandering out here in this godforsaken wilderness? With an effort of will she forced her mind to focus and worked out that weeks must have passed, because the sun was higher in the sky now than when she had set out. As she tugged out her precious bent pin and twine that was wrapped in her pocket and started to trawl clumsily through the water, it occurred to her that the shoots on the birch trees had grown into full-size leaves and the warmth of the sun on her back made her skin come alive.

The first time she came across habitation she almost wept with pleasure. It was a farm, a scrawny subsistence scrap of worthless land, and she crouched behind a birch trunk all day, observing the comings and goings of the peasant couple who worked the place. An emaciated black and white cow was tethered to a fence next to a shed and she watched with savage envy as the farmer’s wife coaxed milk from the animal.

Could she go over there and beg a bowlful?

She stood up and took one step forward.

Her mouth filled with saliva and she felt her whole body ache with desire for it. Not just her stomach but the marrow in her bones and the few red cells left in her blood – even the small sacs inside her lungs. They all whimpered for one mouthful of that white liquid.

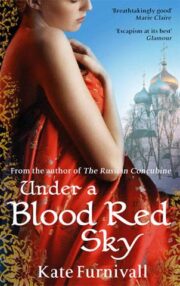

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.