Sofia sat cross-legged on the dirty floorboards without moving. The night was dark and bitterly cold as the temperature continued to plummet, but her muscles had learned control. She had taught herself patience, so that when the inquisitive grey mouse pushed its nose through the rotten planks of the hut wall, its eyes bright and whiskers twitching, she was ready for it.

She didn’t breathe. She saw it sense danger, but the lure of the crumb of bread placed on the floor was too great in the food-less world of the labour camp, and the little creature made its final, fatal mistake. It scurried towards the crumb. Sofia’s hand shot out. One squeak and it was over. She added the miniature body to the three already in her lap and carefully broke the tiny crumb of bread in two, popping one half of it into her own mouth and placing the other back on the floor. She settled down again in the silence.

‘You’re very good at that,’ Anna’s quiet voice said.

Sofia looked up, surprised. In the dim light she could just make out the restless blonde head and delicate pale face on one of the bunks.

‘Can’t you sleep, Anna?’ Sofia asked softly.

‘I like watching you. I don’t know how you move so fast. Besides, it takes my mind off…’ she gestured about her with a loose flick of her hand, ‘… off this.’

Sofia glanced around. The darkness was cut into slices by a bright shaft of moonlight, slipping in through the narrow gaps between the planking of the walls. The long wooden hut was crammed with a hundred and fifty undernourished women on hard communal bunks, all dreaming of food, their snores and coughs and moans filling the chill air. But only one was sitting with a precious pile of food in her lap. Though only twenty-six, Sofia had spent enough years in a labour camp to know the secrets of survival.

‘Hungry?’ Sofia asked Anna with a crooked smile.

‘Not really.’

‘Don’t fancy roast rodent?’

‘Nyet. No, not tonight. You eat them all.’

Sofia jumped up and bent over Anna’s bunk, breathing in the stale smell of the five unwashed bodies and unfilled bellies that lay on the bed board.

She said fiercely, ‘Don’t, Anna. Don’t give up.’ She took hold of her friend’s arm and squeezed it hard. ‘You’re just a bundle of bird bones under this coat. Listen to me, you’ve come too far to give up now. You’ve got to eat whatever I catch for you, even if it tastes foul. You hear me? If you don’t eat, how are you going to work tomorrow?’

Anna closed her eyes and turned her face away into the darkness.

‘Don’t you dare shut me out, Anna Fedorina. Don’t do that. Talk to me.’

Only silence, save for Anna’s quick shallow breathing. Outside the wind rattled the wooden planks of the roof and Sofia heard the faint screech of something metal moving. One of the guard dogs at the perimeter fence barked a challenge.

‘Anna,’ Sofia said angrily, ‘what would Vasily say?’

She held her breath. Never before had she spoken those words or used Vasily’s name as a lever. Slowly Anna’s tousled blonde head rolled back and a smile curved the corners of her pale lips. The movement was barely there, a faint smudge in the darkness, but Sofia didn’t miss the fresh spark of energy that flickered in the blue eyes.

‘Go and cook your wretched mice then,’ Anna muttered.

‘You promise to eat them?’

‘Yes.’

‘I’ll catch one more first.’

‘You should be sleeping.’ Anna’s hand gripped Sofia’s. ‘Why are you doing this for me?’

‘Because you saved my life.’

Sofia felt rather than saw Anna’s shrug.

‘That’s forgotten,’ Anna whispered.

‘Not by me. Whatever it takes, Anna, I won’t let you die.’ She stroked the mittened fingers, then pulled her own coat tighter and returned to her spot by the hole and the crumb of bread. She leaned her back against the wall, letting the trembling in her limbs subside until she was absolutely still once more.

‘Sofia,’ Anna whispered, ‘you have the persistence of the Devil.’

Sofia smiled. ‘He and I are well acquainted.’

3

Sofia leaned against the hut wall, shutting her mind to the icy draughts, and let Anna’s words echo quietly in her head.

That’s forgotten.

Two years, eight months ago. Sofia pulled off the makeshift mitten on her right hand, stitched out of blanket threads and mattress ticking, and lifted the two scarred fingers right up to her face. She could just make out the twisted flesh, a reminder every single day of her life. So no, not forgotten.

It had started when they were taken off axing the boughs from felled trees and put to work on the road instead. It was progressing fast. The prison labour brigades were not told from where it had come nor where it was headed, but the pressure was hard and unrelenting and it showed in the attitude of the guards, who grew more demanding and less forgiving of any delays. People started making mistakes.

Sofia had reached such a state of exhaustion that her mind was becoming foggy and the skin on her hands was shredded, despite the makeshift gloves. Her world became nothing but stones and rocks and gravel, and then more stones and more rocks and more gravel. She piled them in her sleep, shovelled grit in her dreams; hammered piles of granite into smooth flat surfaces till the muscles in her back forgot what it was like not to ache with a dull, grinding pain that saps your willpower because you know it’s never going away. Even worse was the ditch digging. Feet in slime and filthy water all day and spine fixed in a permanent twist that wouldn’t unscrew. Eating was the only aim in life and sleep had become a luxury.

‘Can any of you scarecrows sing?’

The surprising request came from a new guard. He was tall and as lean as the prisoners themselves, only in his twenties and with a bright intelligent face. What was he doing as a guard? Sofia wondered. Most likely he’d slipped up somewhere in his career and was paying for it now.

‘Well, which one of you can sing?’

Singing used up precious energy. No one ever sang. Besides, work was supposed to be conducted in silence.

‘Well? Come on. I fancy a serenade to brighten my day. I’m sick of the sound of your fucking hammers.’

Anna was up on the raised road crushing stones into place but Sofia noticed her lift her head and could see the thought starting to form. A song? Yes, why not? She could manage a song. Yes, an old love ballad would-

Sofia tossed a pebble and it clipped Anna’s ankle. She winced and looked over to where Sofia was standing three metres away, knee-deep in ditch water, scooping out mud and stones. Her face was filthy, streaked with slime and covered in bites and sweat. The summer day was overcast but warm, and the need to keep limbs completely wrapped up in rags against the mosquitoes made everyone hot and morose. Sofia shook her head at her friend, her lips tight in warning. Don’t, she mouthed.

‘I can sing,’ came a voice.

It was a small, dark-haired woman in her thirties who’d spoken. The prisoners close by looked up from their work, surprised. She was usually quiet and uncommunicative.

‘I am an…’ The woman corrected herself. ‘I was an opera singer. I’ve performed in Moscow and in Paris and Milan and-’

‘Excellent! Otlichno! Warble something sweet for me, little songbird.’ The guard folded his arms around his rifle and smiled at her expectantly.

The woman didn’t hesitate. She threw down her hammer with disdain, drew herself up to her full height, took two deep breaths and started to sing. The sound soared out of her, pure and heart-wrenching in its astonishing beauty. Heads lifted, the smiles and tears of the workers bringing life back into their exhausted faces.

‘Un bel dì, vedremo levarsi un fil di fumo sull’estremo confin del mare. E poi…’

‘It’s Madame Butterfly,’ murmured a woman. She was hauling a wheelbarrow piled high with rocks into position on the road.

As the music filled the air with golden enchantment, a warning shout tore through it. Heads turned. They all saw it happen. The woman had dropped her barrow carelessly to the ground as she’d stopped to listen to the singing, and now it had started to topple. It was the accident all of them feared, to be crushed beneath a barrow-load of rocks as they plunged over the edge of the raised road surface. You didn’t stand a chance.

‘Sofia!’ Anna screamed.

Sofia was fast. Knee-deep in water she was struggling to escape, but her reflexes had her spinning out of the path of the rocks. A great burst of water surged up out of the ditch as the rocks crashed down behind her.

Except for one. It ricocheted off the rubble that layered the side of the new road, it came crunching down on Sofia’s right hand, just where her fingers were clinging on to the bank of stones.

Sofia made no sound.

‘Get back to work!’ the guard yelled at everyone, disturbed by the accident he’d caused. Anna leapt into the water beside Sofia and seized her hand. The tips of two fingers were crushed to a pulp, blood spurting out into the water in a deep crimson flow.

‘Bind it up,’ the guard called out and threw Anna a rag from his own pocket.

She took it. It was dirty and she cursed loudly. ‘Everything is always dirty in this godforsaken hole.’

‘It’ll be all right,’ Sofia assured her, as Anna quickly bound the scrap of cloth round the two damaged fingers, strapping them together, one a splint for the other, stemming the blood.

‘Here,’ said Anna, ‘take my glove as well.’

There was an odd chalky taste inside Sofia’s mouth. ‘Thank you,’ she muttered.

Her eyes stared into Anna’s and, though she kept them steady, she knew Anna could see something shadowy move deep down in them, like the first flutter of the wing of death.

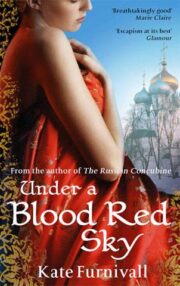

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.