The wind picked up, stealing the last remnants of heat from their bodies. As the prisoners made their way through the trees, Sofia and Anna ducked their faces out of the icy blast, pulling their scarves tighter round their heads. They pushed one exhausted foot in front of the other and huddled their bodies close to each other. This was an attempt to share their remaining wisps of warmth, but it was also something else, something more important to both of them. More important even than heat.

They talked to each other. Not just the usual moans about aching backs or broken spades or which brigade was falling behind on its norm, but real words that wove real pictures. The harsh scenes that made up the daily, brutal existence of Davinsky Camp were difficult to escape, even in your head they clamoured at you. Their grip on the mind, as well as on the body, was so intractable that no other thoughts could squeeze their way in.

Early on, Sofia had worked out that in a labour camp you exist from minute to minute, from mouthful to mouthful. You divide every piece of time into tiny portions and you tell yourself you can survive just this small portion. That’s how you get through a day. No past, no future, just this moment. Sofia had been certain that it was the only way to survive here, a slow and painful starvation of the soul.

But Anna had other ideas. She had broken all Sofia’s self-imposed rules and made each day bearable. With words. Each morning on the two-hour trek out to the Work Zone and each evening on the weary trudge back to the camp, they put their heads close and created pictures, each word a colourful stitch in the tapestry, until the delicately crafted scenes were all their eyes could see. The guards, the rifles, the dank forest and the unrelenting savagery of the place faded, like dreams fade, so that they were left with no more than faint snatches of something dimly remembered.

Anna was best at it. She could make the words dance. She would tell her stories and then laugh with pure pleasure. And the sound of it was so rare and so unfettered that other heads would turn and whimper with envy. The stories were all about Anna’s childhood in Petrograd before the Revolution, and day by day, month by month, year by year, Sofia felt the words and the stories build up inside her own bones. They packed tight and dense in there where the marrow was long gone, and kept her limbs firm and solid as she swung an axe or dug a ditch.

But now things had changed. As the snow began to fall and whiten the shoulders of the prisoners in front, Sofia turned away from them and faced Anna. It had taken her a long time to get used to the howling of a Siberian wind but now she could switch it off in her ears, along with the growls of the guard dogs and the sobs of the girl behind.

‘Anna,’ she urged, holding on to the rope that bound them together, ‘tell me about Vasily again.’

Anna smiled, she couldn’t help it. Just the mention of the name Vasily turned a light on inside her, however wet or tired or sick she was. Vasily Dyuzheyev – he was Anna’s childhood friend in Petrograd, two years older but her companion in every waking thought and in many of her night-time dreams. He was the son of Svetlana and Grigori Dyuzheyev, aristocratic friends of Anna’s father, and right now Sofia needed to know everything about him. Everything. And not just for pleasure this time – though she didn’t like to admit, even to herself, how much pleasure Anna’s talking of Vasily gave her – for now it was serious.

Sofia had made the decision to get Anna out of this hell-hole before it was too late. Her only hope of succeeding was with help, and Vasily was the only one she could turn to. But would he help? And could she find him?

A quiet and thoughtful smile had crept on to Anna’s face. Her scarf was wrapped round her head and the lower part of her face, so that only her eyes showed, narrowed against the wind. But the smile was there, deep inside them, as she started to talk.

‘The day was as colourless as today. It was winter and the new year of 1917 had just begun. All around me the white sky and the white ground merged to become one crisp shell, frozen in a silent world. There was no wind, only the sound of a swan stamping on the ice of the lake with its big flat feet. Vasily and I had come out for a walk together, just the two of us, wrapped up well against the cold. Our fur boots crunched satisfyingly in the snow as we ran across the lawn to keep warm.

‘“Vasily, I can see the dome of St Isaac’s Cathedral from here. It looks like a big shiny snowball!” I shouted from high up in the sycamore tree. I’d always loved to climb trees and this was a particularly tempting one, down by the lake on his father’s estate.

‘“I’ll build you a snow sleigh fit for a Snow Queen,” he promised.

‘You should have seen him, Sofia. His eyes bright and sparkling like the icicle-fingers that trailed from the tree’s branches, he watched me climb high up among its huge naked limbs that spread out over the lawn like a skeleton. He didn’t once say, “Be careful” or “It’s not ladylike”, like my governess Maria would have.

‘“You’ll keep dry up there,” he laughed, “and it’ll stop you leaping over the sleigh with your big feet before it’s finished.”

‘I threw a snowball at him, then took pleasure in studying the way he carefully carved runners out of the deep snow, starting to create the body of a sleigh with long, sweeping sides. At first I sang “Gaida Troika” to him, swinging my feet in rhythm, but eventually I couldn’t hold back the question that was burning a hole in my tongue.

‘“Will you tell me what you’ve been doing, Vasily? You’re hardly ever here any more. I… hear things.”

‘“What kind of things?”

‘“The servants are saying it’s getting dangerous on the streets.”

‘“You should always listen to the servants, Annochka,” he laughed. “They know everything.”

‘But I wasn’t going to be put off so easily. “Tell me, Vasily.”

‘He looked up at me, his gaze suddenly solemn, his soft brown hair falling off his face so that the bones of his forehead and his cheeks stood out sharply. It occurred to me that he was thinner, and my stomach swooped when I realised why. He was giving away his food.

‘“Do you really want to know?”

‘“Yes, I’m twelve now, old enough to hear what’s going on. Tell me, Vasily. Please.”

‘He nodded pensively, and then proceeded to tell me about the crowds that had gathered noisily in the Winter Palace Square the previous day and how a shot had been fired. The cavalry had come charging in on their horses and flashed their sabres to keep order.

‘“But it won’t be long, Anna. It’s like a firework. The taper is lit. It’s just a question of when it will explode.”

‘“Explosions cause damage.” I was frightened for him.

‘From my high perch I dropped a snowball at his feet and watched it vanish in a puff of white.

‘“Exactly. That’s why I’m telling you, Anna, to warn you. My parents refuse to listen to me but if they don’t change their way of living right now, it’ll be…” he paused.

‘“It’ll be what, Vasily?”

‘“It’ll be too late.”

‘I wasn’t cold in my beaver hat and cape but nevertheless a shiver skittered up my spine. I could see the sorrow in his upturned face. Quickly I started to climb down, swinging easily between branches, and when I neared the bottom Vasily held out his arms and I jumped down into them. He caught me safely and I inhaled the scent of his hair, all crisp and cool and masculine, a foreign territory that I loved to explore. I kissed his cheek and he held me close, then swung me in an arc through the air and gently dropped me inside the snow sleigh on the seat he’d carved. He bowed to me.

‘“Your carriage, Princess Anna.”

‘My heart wasn’t in it now, but to please him I picked up the imaginary reins with a flourish. Flick, flick. A click of my tongue to the make-believe horse and I was flying along a forest track in my silver sleigh, the trees leaning in on me, whispering. But then I looked about suddenly, swivelling round on the cold seat. Where was Vasily? I spotted him leaning against the dark trunk of the sycamore, smoking a cigarette and wearing his sad face.

‘“Vasily,” I called.

‘He dropped the cigarette in the snow where it hissed.

‘“What is it, Princess?”

‘He came over but he didn’t smile. His grey eyes were staring at his father’s house, three storeys high with elegant windows and tall chimneys.

‘“Do you know,” he asked, “how many families could live in a house like ours?”

‘“One. Yours.”

‘“No. Twelve families. Probably more, with children sharing rooms. Things are going to change, Anna. The Tsarina’s evil old sorcerer, Rasputin, was murdered last month and that’s just the start. You must be prepared.”

‘I tapped a glove on his cheek and playfully lifted one corner of his mouth. “I like change.”

‘“I know you do. But there are people out there, millions of them, who will demand change, not because they like it but because they need it.”

‘“Are they the ones on strike?”

‘“Yes. They’re desperately poor, Anna, with their rights stolen from them. You don’t realise what it’s like because you’ve lived all your life in a golden cage. You don’t know what it is to be cold and hungry.”

‘We’d had arguments before about this and I knew better now than to mention Vasily’s own golden cage. “They can have my other coat,” I offered. “It’s in the car.”

‘The smile he gave me made my heart lurch. It was worth the loss of my coat. “Come on, let’s go and get it,” I laughed.

‘He set off in long galloping strides across the lawn, leaving a trail of deep black holes in the snow behind him. I followed, stretching my legs as wide as I could to place my fur boots directly in each of his footsteps, and all the way I could still hear the wind tinkling in the frozen trees. It sounded like a warning.’

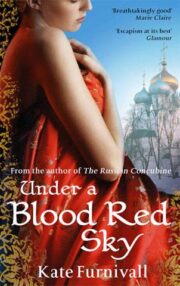

"Under a Blood Red Sky" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Under a Blood Red Sky" друзьям в соцсетях.