“Where do you think they are?” I said at last, giving voice to the thought that had been running a loop in my head ever since Kolby had told me that trucks had made it through.

Kolby looked down at his feet. He knew who I was talking about without me even saying it. “I don’t know. Where were they when it hit?”

“Mom and Marin were at dance. I don’t know where Ronnie was. But…” I trailed off, unable to say what had been weighing on my mind. If they could have gotten through, they would have. Mom would have come to get me. She’d have been scared out of her mind for me.

If they weren’t here, it was because something was keeping them from coming.

“We can go there,” Kolby said. “It’s not that far.”

My hand shook, the water inside the bottle rippling with the motion. “It’s a couple miles, at least.”

He motioned toward our houses. “It’s not like there’s anything good on TV right now,” he said, and though he was joking, neither one of us laughed. Nothing about any of this was funny. “Let me tell Tracy, so my mom won’t worry when she wakes up,” he said.

And before I could say anything in protest, he loped off toward Mrs. Donnelly’s cellar.

Part of me was definitely ready to do this. To go out and find my mom and Marin and Ronnie. If they couldn’t get to me, I’d get to them.

But part of me was scared.

What if I didn’t find them?

What if they weren’t there to be found?

CHAPTER

SEVEN

More and more vehicles were creeping down Church Street by the time we got to it, some of them stopping to pick up people who were still walking toward town, still hoping to find help. Some passengers offered bottles of water and first-aid kits. Others rolled by with cameras, taking photos and gabbing about the devastation as if it were there for their entertainment.

By comparison, all the people who were walking looked filthy and grim. Some wore stony, distant expressions, as if they had no idea where they were or where they were going. Some were carrying children. Some were covered in dried blood. Some were telling stories, and all of the stories were similar—the house fell apart, the wind tugged at us, we got hit with something, our houses are gone, our cars are gone, our streets are gone, our lives, as we knew them, are gone.

“About a half mile that direction will get you out of the storm’s path,” one woman told Kolby, pointing to the east. “It ran north and south, so if you go east, before long you’ll come to regular pavement.”

So we walked east on Kentucky, taking in the devastation there as we headed toward normalcy.

“You smell that?” Kolby said, wrinkling his nose. “Stinks.”

I thought about the hamburger I’d crumbled up in the skillet right before the storm hit. Who knew where it had been flung, but wherever it was, it was rotting in the sun now, along with dinners and the refrigerator guts of hundreds of other houses.

“Smells like the washing machine when I forget to take the wet clothes out,” I said.

“It’s only gonna get worse, you know,” he said. “That smell. All that wet stuff and the heat.”

“Food rotting,” I added.

“And people,” Kolby said, and he said it so matter-of-factly, I stopped walking and stared at him.

“What?” he asked, turning to face me and shrugging. “There are dead people under some of this stuff. And dead animals, too. It’s reality.”

I started walking again. “Yeah, but you don’t have to say it like that. Like it’s no big deal.”

“I don’t like it, either,” he mumbled, following me.

We came up over a hill and could see where the destruction stopped, not too many yards ahead of us. It was strange, seeing how the houses went from totally razed to beat up and broken to lightly damaged to completely fine. Literally, where one house was gone, the neighbor three houses down would only need to replace some shingles.

It was at that end of the street where most of the people were congregating. Chain saws buzzed and whole crowds sifted through rubble, people calling out to one another, offering help and drinks, the effort much more concerted than on our street. Someone had set up a few tents and folding tables covered with food and drinks and tools and supplies. Two of the tents shaded an assortment of lawn chairs, and some women sat there with babies. Little kids squatted on the ground and munched on grapes, watching as Kolby and I scuffed by.

“You all right?” a woman hollered to us from one of the chairs. “You need help?”

“We’re fine,” I yelled back, smiling as if we were simply out on a midday stroll.

“You need something to eat?” she called. “There’s plenty. None of us has power, so we’ve got to eat it while it’s still good.”

My stomach growled, and Kolby and I looked at each other. We diverted to the tent, where I immediately grabbed a banana and Kolby palmed a sandwich, taking a huge bite out of it and closing his eyes while he chewed.

“You’re hurt,” the woman said, softer now as she approached us. “We’ve got bandages. Is it bad?”

“It’s okay,” Kolby said, but I overrode him.

“It’s pretty bad. How big are your bandages?”

The woman rifled through the first-aid kits, then disappeared into her house. Kolby and I snacked while we waited, shoving crackers and cheese cubes into our mouths greedily. She came back out with a roll of gauze and some tape.

“It’s kind of old, but it’s going to be better than that,” she said, handing me the gauze.

We made our way over to the chairs and Kolby peeled off the bandanna and clothesline from his arm. I winced when I looked at the cut, the skin around the edges swollen and angry red.

“You’re gonna want to keep that clean,” the woman said, making a pained face. “It looks pretty bad. What did you cut it on?”

“Glass,” Kolby answered.

“Good, at least it wasn’t rusted metal. You’re probably gonna need a tetanus shot anyway. Although I don’t know where you’d go to get one right now,” she said. “I suppose the Elizabeth Clinic was spared yesterday, but it’s probably packed. And nobody has power.”

“I’m sure it’ll be fine,” Kolby said as I wrapped the gauze around his arm and secured it with a strip of tape. “How far did the tornado go, do you know?” he asked.

“My husband drove around this morning,” the woman said. “About seven miles or so. Hit some of the schools, the library, the hospital, the police station, fire station. Hit everything. You two need a ride somewhere? I’m sure Jerry’ll take you.”

“We’re going to Janice’s Dance Studio,” I said. “That’s where my mom was. She hasn’t come home yet, and I’m trying to find her.”

The woman’s face paled. “On Sixth?” I nodded. “Oh, honey, he won’t be able to get you in there. Sixth got hit bad.”

“Oh. Okay,” I said, trying to ignore the lump that had suddenly formed in my throat. “We’ll walk.”

The woman offered a smile that didn’t quite hold up the corners of her mouth. “I hear they’re setting up tents at some of the churches,” she said. She looked at Kolby and lowered her voice, as if I weren’t standing right there. “They’ll be starting to compile lists. There’s a Lutheran church right around the corner on Munsee Avenue.”

Kolby nodded and grabbed my elbow, pulling me back into the street.

“What kinds of lists?” I asked when we got a little way down the road.

He took a long time to answer. “Of missing people,” he finally said. “And… you know…”

My heart went cold. “I know what?”

He stopped, still holding my elbow, his knuckles grazing my side. Ordinarily, I would be mortified at a boy touching my side, afraid that he’d feel the wobbly skin there. But I was too intent on hearing him say it aloud—that they would be compiling lists of the missing and the dead—to worry about something so stupid as whether or not I was stick-skinny. “Come on, Jersey, it doesn’t matter,” he said. “We’ll go to Janice’s and see what’s up before we worry about what kind of lists they’ve got at the churches. Just because she said it doesn’t make it true.”

When we turned onto Sixth Street, we navigated in the direction we’d come from, making our way back into the heart of the destruction. Under normal circumstances, I knew this part of town like the back of my hand, but the farther west we went, the harder it was to recognize anything. The woman had been right—Sixth Street had been hit bad, most of the buildings ripped right off their foundations, no leaning walls here. There were no signs, no street markers, no landmarks at all. Other than a handful of people determinedly digging through debris where Fenderman’s Grocery used to be, there weren’t even any people.

“I think it was here,” I said, stopping and facing a mostly bare rectangle of concrete. Around the concrete was mud; even the grass had been stripped. It was almost as if the tornado had tried to dig down into the ground with its twisting fingers and scoop Janice’s off the earth.

Kolby walked over to the concrete and bent to pick up something. It was a small ballet shoe. Too small to have been Marin’s, but still the sight of it brought tears to my eyes.

“They aren’t here,” I said. Kolby dropped the shoe. I tried to remember where the cloak closet was—it had been a while since I’d come to the studio with Mom and Marin, and I was turned around by everything being gone. I stumbled across the concrete to the far corner. Where walls had once been anchored into the floor, now just a few splintered boards stuck up from the ground. There were a couple of empty gym bags caught on a ripped-off piece of stud, but otherwise there was nothing.

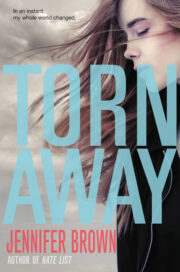

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.