A couple of the men were able to wrench open a car door, and a few people climbed inside. The windows fogged and it was like they were gone. Saved.

And then the wind picked up and began to drive the rain sideways into our ears, and our hair began to drip, and it felt good, but it also felt cold, and we couldn’t help wondering what was next for us, especially after Kolby’s mom began praying, “Dear God, please let there not be another tornado on the way,” and it wasn’t clear if she was actually praying for this or just stating the same fear that had begun to trickle into all of our minds.

Some of the neighbors worked together to prop a piece of wallboard up against the side of what was left of their house, and they huddled under it, their clothes soggy, their feet sinking into the now-saturated debris. Tears began to flow along with the rain as the reality of what had happened to us truly began to sink in.

Kolby’s mom and sister joined them, and soon it was Kolby and me standing in the street alone, blinking at each other through raindrops clinging to our eyelashes.

“There was this guy,” he said, now that it was just the two of us. He blinked off into the distance, took a breath, and turned his gaze back to me. “It was like… like he’d been hit by a bomb. He was in half, Jersey. I didn’t even see where his legs had gone. I think they were buried.”

“Oh my God. What about Tracy?”

“She didn’t see it. Mom kept walking with her. But I can’t stop seeing it, you know? I don’t think I ever will.”

I touched his shoulder lightly, then, embarrassed, pulled my hand away.

“I puked,” he said. “And I feel like such a pussy for puking. It’s…” He shook his head. “Forget it.”

The rain drove into us. I didn’t know what to say to him about the half-man or about his puking. I didn’t know what he wanted from me. Our relationship had always been about playing pickup games of baseball or tag or building forts and riding bikes. We didn’t talk about puking, or crying, or being scared.

And I was. I was so, so scared.

“I’m going inside,” I said, like I’d said to him a million times before. Like I was tired of playing hide-and-seek or wanted to watch TV or eat dinner or something else totally ordinary.

“Inside where?”

I gestured to what was left of my house. “Basement. In case…” In case of another tornado. “In case my mom comes home.”

He shook his head. “You shouldn’t go back in there. It’s not stable. Look how it’s leaning. And the ceiling’s been ripped out.”

“It’ll be okay. It’s better on the inside.” Which was a total lie, but the more the thunder roared above us, the more Kolby’s haunted eyes transferred that image of the half-man into my soul, the more his mom prayed into the wind, the more frightened I became. Please, God, don’t make me have to go through another tornado. Not again. Not alone.

My heart started pounding and I started breathing heavy and I knew I needed to get back into the basement, back to where I’d been safe, right away. “I’ll come out when the rain stops.”

Kolby grabbed my arm and I gently pulled away from him. I smiled. Or at least tried to. It felt like a smile, anyway.

“I’ll be fine, Kolby. You should be with your mom and Tracy right now.”

A bolt of lightning crashed and we both jumped.

“You want me to go with you?” he asked, though I could tell by the way he stared anxiously at the house that he wanted the answer to be no. I could tell he felt torn between protecting me and protecting his mom and sister.

I didn’t want him there. Kolby was a great friend, and a part of me wanted to latch on to him and hope he could keep me safe. But for some reason, the devastation behind that leaning half-wall of my house felt too personal, too embarrassing. It was my family’s life, all bunched up and bundled and twisted into heaps, and I didn’t want him to see it, even though I knew that most of our stuff was probably lying on the street right now, getting turned into mush by the rain, and that most of his stuff was, too.

“It’s okay. I’ll be fine,” I said. “When my mom comes, tell her I’m inside, okay?”

“Okay,” he said reluctantly. “But if you need anything…” He trailed off, probably thinking exactly what I was thinking, which was What? If I need anything, what? What can you do? You lost everything, too.

I nodded and turned back toward my house on shaking legs.

There was more thunder, and my heart pounded as I climbed the steps and slipped in through the front door.

My brain expected to find the scene on the other side of the door exactly like it had always been. Brown carpet, vacuum lines still scratched through it from Monday’s chores. The TV on. The wall of mirrors behind the dining room table—a throwback from when the house was built in the 1970s—reflecting our mismatched garage-sale table and chairs. The white linoleum with the pale blue flowers stretching into the kitchen, the light of the dishwasher blinking to indicate that the dishes inside were clean. The hum of the refrigerator and the air conditioner.

Instead, it was raining. Inside my house. The wet plaster of the fallen walls smelled chalky. The only sound was the rumbling of the sky.

I tried to make out something familiar. And finally I did. The television stand was missing. But the television sat there in its place, as if someone had picked up the TV and taken the stand, then set the TV back down. Of course, what use was a TV when there was no outlet to plug it into?

Marin’s purse was still on the chair where I’d left it. I opened it and looked inside, leaning my head over it to try to keep the relentless rain out.

It was filled with three packs of gum and a tube of iridescent pink lipstick that Mom had handed down to her. Marin’s treasures.

I looped the purse over my arm and headed along the path I’d cleared earlier, trying hard not to step on anything sharp or dangerous, picking my feet up high with each step and placing them down carefully. There was so much broken glass.

When I finally made it to the bottom step, I was out of the rain’s reach, so I stood there and stared, squeezing water out of my hair and wiping my cheeks dry with my hands, trying to figure out what to do next.

Trying to figure out how I would survive until Mom and Ronnie came home.

CHAPTER

SIX

There were a dozen bottles of water in Ronnie’s mini-fridge, along with a few beers, some cheese in a jar, and a package of hot dogs. I’d had to dig through broken boards and rubble with my hands to get to the refrigerator. By the time I unearthed it, I was so thirsty, I downed one of the waters while I sat on a clear spot on the floor in front of it, my fingers torn up and sore.

My stomach growled heartily as I spotted the cheese, but I was afraid to eat it, unsure what we would do about food once Mom and Ronnie and Marin came home. I wanted to make sure there was enough for all of us. I wondered when we would get help on our street, and if the helpers would have food. I wondered if our real refrigerator was still upstairs somewhere, and if it still had food in it, and tried to bat away a panicked thought that the refrigerator upstairs could at any minute cave in the floor it was sitting on and bury me. I scooted back from the area where the kitchen had spilled into the basement, into the opposite corner. That section of floor had felt solid.

I sat on the concrete and sipped my water, listening to the thunderstorm, watching as the rain picked up and tapered off, only to do it again, bathing the basement in shadows that got deeper and deeper as night fell full force.

I didn’t hear anything else outside. No voices, no sirens, no cars. Just the tapping of the raindrops, the clap of the thunder.

Eventually, I got up and made my way over to the flipped couch; it was wet on the back side, but the cushions underneath were dry. I pulled them out and carried them to the pool table, which I’d pushed closer to my safe corner. I placed the couch cushions under the table and rounded up my backpack, Marin’s purse, the flashlight, and my cell phone. I rummaged through an old dresser that Mom had stuck in the farthest corner of the basement, and found a blanket we used for picnics and on the Fourth of July to watch fireworks at the park, some beach towels, and a deck of playing cards with the date of Mom and Ronnie’s Vegas honeymoon embossed on the box. I took them all, lumping the towels together like a pillow and covering myself with the blanket. I stuffed the playing cards into Marin’s purse, along with the gum and the lipstick, and then clicked on the flashlight and stretched out across the cushions on my stomach, feeling safer, as if I could wait for everyone down here until morning if need be. I didn’t want to, but I’d be okay if I had to.

The book I’d been reading before the tornado hit—which seemed like forever ago already—was a little damp, and one of the pages had been torn. But for the most part it was all still there, and I decided to finish it to pass the time. I wondered if Miss Sopor’s house had been destroyed, too, and if the high school was still standing.

Surely it was. It had to be. Jane might have been inside it.

I imagined everyone going back to school, with stories to tell about how they’d weathered the storm. About how their houses were damaged or their cars were messed up. What about Jersey Cameron and Kolby Combs? I imagined them saying. They aren’t here. I heard they lost everything. I didn’t want them doing that. I didn’t want everyone talking about how Jersey Cameron, the mousy drama club girl, had nothing now. I groaned and rolled to my back, staring up at the bottom of the pool table, the book slack in my hands. With my free hand, I dug my cell phone out of my pocket and tried to call Mom again. Still nothing. Where are you, Mom? When will you get to me?

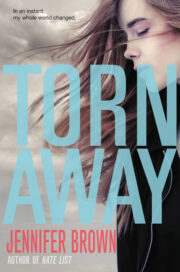

"Torn Away" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Torn Away". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Torn Away" друзьям в соцсетях.