The weekend after I’d met Jared Baker of the Princeton Fertility Clinic, I made my monthly trip home. I left at four, after my last class on Friday, stopping at the Wawa, the convenience store at the edge of campus where students could buy cheap hot dogs and hoagies after a night of drinking. I filled my thermos with hot coffee and bought a ticket for the Dinky, the little train that ran from campus to Princeton Junction. At Princeton Junction I’d catch a New Jersey Transit train to Philadelphia. In Philly, I’d walk from Suburban Station to the bus terminal and buy a bottle of water and a roast pork sandwich at the Reading Terminal Market, standing in line with rough-handed construction workers and puffy-faced nurses on their way to work, and catch the Greyhound home.

When I got to Pittsburgh early the next morning, my mother was waiting for me at the station, the sounds of NPR filling the car. NPR was my father’s station — my mother favored country music and AM call-in shows. All those years later, after his hospitalization, his trips through detox and rehab, his trial for driving under the influence and attempted vehicular manslaughter and the six months he’d eventually spent in jail, she still listened to his radio stations, still kept one of his coats in the closet and cooked his favorite things for dinner, as if, someday, he’d walk back through the door, the same man she’d fallen in love with.

It would never happen. My father had lived at home briefly after he’d been paroled. Then the drinking had started again. My mother had given him a version of the speech it was rumored Laura Bush once delivered to her not-yet-presidential husband—“It’s me or Jack Daniel’s”—and kicked him out. My father had rented a studio apartment and, once that lease ran out, he’d moved in with another woman.

My mom could have forgiven my father for what he’d done, for driving drunk, for hitting an innocent woman and child, but she couldn’t forgive him for Rita Devine. It had soured my mother, who’d always been so sweet, delighted by the smallest things: a trip to the shore, a bouquet of sunflowers, a mug of mulled cider in the backyard while my brother and I raked leaves.

I dropped my backpack in the trunk, kissed my mom’s cheek, and buckled myself into the front seat. My mother drove with a light hand on the wheel, steering the car through the morning sunshine, along the familiar streets, until we merged onto the freeway that would take us from downtown to Squirrel Hill. “Classes okay?” she asked.

“Classes are fine,” I told her.

“And how is Dan?”

“Dan’s great.” Dan and I had been a couple for four months, but sometimes I thought I didn’t know him any better than I had the first night we’d hooked up. He was good-looking, well-mannered, a rower with formidable shoulders, and had a fondness for 1990s-era grunge rock…and that was it. “Well, you look great,” said my mom and I nodded.

My mother and I have the same fair skin and pale eyes, and I know, from pictures, that her hair was once like mine. But now her skin was etched with hundreds of tiny lines, blotched and splotched with souvenirs of the summers when she used to gild herself in Johnson’s Baby Oil and lie in a bikini on a beach towel in her backyard. The pink of her lips had faded to beige, her hair was a too-bright lemony color, her fingertips were permanently stained from hair dye and cigarettes, and her body was slack and soft beneath her clothes.

“I hope you’re hungry. I made a chicken pot pie for dinner.” She gave me a quick once-over when traffic slowed. “You look great.”

“I’ve been running a lot. Five miles yesterday.”

“Five miles. Wow. Good for you.” She looked at herself ruefully. “I bet I couldn’t run a mile. Not even if someone was chasing me.”

“You just start slow. Run for thirty seconds, walk for two minutes. Start with twenty minutes a day…”

She shook her head, smiling. She’d heard this before, my prescriptions for healthy living, advice about diet and exercise, and she’d listen with a smile, then ignore whatever I’d suggested. As far as I knew, she’d never been on a date since my father had left. “I’m just not interested,” she’d told me the one time I’d asked.

My father and his girlfriend lived in an apartment complex, a place called Oakwood Towers that boasted no oak trees and where the buildings topped out at three stories. The three-building complex, shaped like an H, was Section 8 housing, with a parking lot full of secondhand cars held together with Bondo and tape and baling wire, and apartments full of new immigrants and newly single men, families who’d cram eight or ten people into a one-bedroom unit, tired-eyed grandparents with babies and toddlers. My mother would drive into the parking lot, but no farther.

“See you at two?”

I nodded, leaving my backpack in the car, taking the plastic bag full of stuff I’d brought for my father. On the scraggly lawn in front of his building, two boys in corduroy pants and Tshirts kicked a soccer ball back and forth and chattered to each other in a language I didn’t recognize.

I pressed the buzzer, waited until the door opened, and then walked past the empty fountain in the lobby (sometimes there was a girl in a football helmet sitting on the lip of that fountain, rocking and drooling), down a disinfectant-scented, green-carpeted hallway to apartment 211.

Rita wasn’t there — she worked on weekends, a part-time job at a sporting-goods store. My dad was waiting for me at the door. He’d gained weight since his time in jail, and now his face was red, his fingers thick, his hands and cheeks swollen as he hugged me and said my name in his hoarse, raspy voice. He smelled like cigarette smoke, but nothing worse: sometimes when I’d hug him I could catch a whiff of whiskey or the strange, chemical odor I could only guess was drugs, but not today.

“Come in,” he said, leading me through the cluttered living room. Coffee mugs and sections of newspaper and DVD cases sat on every table; clothes were piled on the couch and the chairs. The windows were streaked with dirt; the pillows on the sofa were squashed; the knickknack shelf where Rita kept a few framed family photographs and some china plates and crystal glasses was dusty. My dad walked to the little kitchen, where there was a frying pan on the stove and three teacups beside it, one with cut-up onions, one with green peppers, and one with grated cheese. “I’m making a Denver omelet.”

“That sounds good.” I watched as he scooped a spoonful of margarine from a tub and put it in the pan to melt. His hands were shaking, but this could have meant almost anything: some of the drugs he’d been prescribed had tremors as a side effect, or he could have been going through withdrawal, or he could have been high, right at that moment, for all I knew. After all the years, I’d never gotten any good at telling.

I found forks and knives in a drawer, plates in a cabinet, and two juice glasses in the dishwasher. My father was concentrating hard on the pan. He’d dumped in the onions, which were cut in large, ragged chunks. He shook his head, then picked up a spatula, the end still crusted with melted cheese. I poured us small glasses of generic orange juice — as part of his disability payments, my father got food stamps, although they weren’t stamps anymore, just what looked like a regular debit card to use at the grocery store — and found paper napkins and a loaf of wheat bread for toast. I was starting to straighten up the living room when he called me in for breakfast. Feeling uncomfortable and out of place, the way I always did in his apartment, I took the seat across from him at the table. The eggs were burnt dark-brown in places, and he’d forgotten the peppers.

“It’s really good,” I told him.

My father sighed. “Ah, I’m no cook. That was your mother.”

I didn’t answer, watching as he maneuvered a bite into his mouth. If he missed us, this was as close as he’d come to saying so. An onion fell off and got stuck in his beard. “Dad,” I said quietly, pointing, and waiting until he’d used his napkin to get it out.

If you saw my father on the street, walking or sitting on the bench outside the duck pond behind his building, you wouldn’t cross the street to avoid him. Maybe you’d think that he was just a regular guy enjoying the sunshine, a man with a job and a family and a house to come home to. If you looked a little closer you’d see the thumbprints smeared on his glasses, the way one of the earpieces was mended with duct tape, the way his skin was unnaturally red and his eyes filmy. If you noticed that, maybe you would pick up your pace and try to put the sight of him out of your mind. You wouldn’t want to think about how many people like him there were out in the world, unsupervised, untethered, unloved. At least you’d want to believe they were untethered and unloved, that they didn’t have wives, or sons, or daughters, because you certainly wouldn’t want to think about that.

I put my fork down on my plate. “Hey, Dad,” I said, “if I could pay for you to go to rehab, would you go?”

He didn’t answer right away. I looked at him, his swollen face, his greasy hair. He used to be handsome. He used to wear suits on the first day of school, no matter how hot it was. He used to kiss my mother in the kitchen when he came home from work, grabbing her around the waist and lifting her briefly into the air as she laughed. He used to live in a house with three bedrooms and an above-ground swimming pool. . but I stopped those thoughts before they got too far.

He pulled off his glasses and turned them over slowly. “It’s not your job,” he finally said. “Not your job to take care of me.”

“I’m almost done with school,” I said, pulling out the pages that I’d printed and passing them across the table. Willow Crest: A Community of Care. I’d done enough research to show that the place was conveniently located and well-regarded, with a respectable success rate. The intake counselor I’d talked with the day before said that they’d have a bed available within the next three weeks. “I’ve got some money to spare. Would you go?”

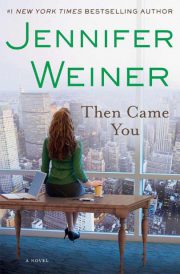

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.