“And he’s lonely,” said Tommy.

I exhaled. This was the truly infuriating part. If our father had serially discarded his wives, trading up for younger, hotter models, we’d have rolled our eyes and agreed that he was getting what he deserved with the world’s Indias. But our mother had left him. After all her time in Manhattan, her years as a stay-at-home mom, a PTA volunteer, a fund-raiser for cancer research and the preservation of historic churches, she’d fallen under the sway of her yoga instructor, one Michael Essensen of Brick, New Jersey, who, after a six-week sojourn in Mumbai, had renamed himself Baba Mahatma and opened a yoga center and spiritual retreat five blocks from our apartment. The Baba, as my brothers and I called him, started popping up in passing in my mother’s conversation: The Baba says Americans should eat a more plant-based diet. The Baba says colonics changed his life. A few months after she’d started taking classes, we would come home from school and find the Baba himself in the kitchen, in all his ponytailed, tattooed, yoga-panted splendor, dispensing wisdom over a pot of green tea. “Oh, hi, guys,” my mother would say, blinking like she was trying to remember our names. The Baba, who had a chiseled chin and an artificial tan and flowing locks inspired by Fabio, would give us an indulgent nod, pour more tea for both of them (never offering me or my brothers a cup), and continue talking about whatever cleanse or fast or ritual he was endorsing that week. At fourteen, I’d been able to identify his spiel as incense-scented nonsense, but my mother had believed every word of it, swearing to her friends (and, eventually, to the strangers she’d corner in the schoolyard or the dentist’s office or the fish counter at Russ & Daughters) that the Baba was magical, and that his ministrations had helped her survive the mood swings and hot flashes of menopause when the hormone therapy prescribed by the top doctors in Manhattan had failed.

My mother had been born Arlene Sandusky in a suburb of Detroit in 1958. She’d married my father at twenty-three, then moved to New York, where she’d had three children and become an enthusiastic baker of cookies and trimmer of Christmas trees, a woman who liked nothing better than taking on some elaborate holiday-related project — assembling and frosting a gingerbread house, or running the schoolwide Easter egg hunt. In the wake of her association with the Baba, she’d ditched her traditions and her Martha Stewart cookbooks. She’d grown her hair long and let it go gray. She’d swapped her designer suits and high heels for embroidered tunics and thick-strapped leather sandals, and traded her Bulgari perfume for a mixture of essential oils that made her smell like the backseat of a particularly malodorous taxicab, sandalwood and curry with hints of vomit. She’d gotten a belly piercing that I’d seen and a tattoo that I hadn’t — I hadn’t even been able to bring myself to ask where or of what—and, eventually, she began slipping the Baba tens of thousands of dollars. When my father’s accountants finally started to ask questions about what the Order of New Light was and whether it was, in fact, a tax-free C corporation, she’d announced her intentions to get a divorce and follow the Baba to Taos, where he was building a retreat offering intensive yoga training, raw cuisine, and a clothing-optional sweat lodge.

I came home from school one afternoon and found luggage lined up in the hall and my mother in her bedroom, packing. “I am renouncing the meaninglessness of the material,” she said, sitting on top of her Louis Vuitton suitcase to get the zipper closed. I pointed out that the meaninglessness of the material did not seem to cover the great quantity of Tory Burch tunics and Juicy Couture sweat suits that she had packed.

“Oh, Bettina,” she said, in a tone that mixed scorn and, unbelievably, pity. “Don’t be so rigid.” She kissed me, taking me into her arms for an unwelcome and musky embrace.

“Be good to your father,” she said, smoothing my hair as I tried not to wriggle away. “He’s a good man, but he’s just not very evolved.”

After that, my mother communicated by letters and postcards, while my father became Topic A in the gossip columns and, when he started dating again, prey for single ladies of a certain age. There was the magazine editor famous enough to have been skewered in a movie, played by an actress who, in my opinion, was ten years too young and significantly too pretty to be a plausible standin. She was followed by a real-estate mogul with a face permanently frozen into a look of startled puzzlement, then a newspaper columnist, similarly Botoxed, who’d made a career out of being bitchy on the Sunday-morning political chat shows. In that realm of gray-suited, gray-faced men, it turned out that even a not-terribly-attractive fifty-two-year-old could pass herself off as a babe if she wore pencil skirts, kept her hair dyed, and made the occasional reference to oral sex.

Even when my father was technically attached, it didn’t stop other women from trying. There would be a hand that lingered on his forearm, a cheek kiss that ended up grazing his lips, a business card with a cell phone number scribbled on it, pressed into his palm at the end of a night. My father had resisted them all, the waitresses and the young divorcees and the actress-slash-models… which was why it made no sense that he’d fall for this hard-edged, new-nosed, fake-named “India,” who was no more in her thirties than I was the winner of America’s Next Top Model.

“Are you worried she’s going to spend our inheritance?” Tommy asked, spinning the wheel of his lighter.

“It’s not about the money,” I said, ignoring the twinge I felt at the thought of this stranger squandering what should have been mine. I had a trust fund, worth ten million dollars, that I’d be able to access on my twenty-first birthday, which was coming in two months. My father had already told me he’d buy me an apartment after I graduated, in whatever city I ended up working. Needless to say, I had no student loans. I’d most likely get a job that offered health insurance, and I’d inherited all the clothes, shoes, furs, and jewelry that my mother hadn’t sold before decamping to New Mexico. Even if my father married some grasping bitch (unlikely) and didn’t sign a prenup (even more unlikely), my brothers and I would be fine. I knew, for example, that my dad had already set up a trust for Trey’s daughter, Violet, and that he’d bought new amps for Dirty Birdy, which specialized in thrash-metal covers of female singer-songwriter ballads.

I ground my cigarette under my heel. “It’s not the money, it’s the principle of the thing. This woman just thinks she can waltz on in here and have. .” I waved my hands out at the lawn, which rolled, lush and green, down a gentle slope to the ocean. “… all of this, and she didn’t earn any of it.”

“Well, when you think about it,” Tommy said, “we didn’t exactly earn any of it, either.”

“We survived Mom and Dad,” I reminded him. I’d given the matter of what we were and were not owed considerable thought. . sometimes while I was walking into what passed for downtown Poughkeepsie so my roommates wouldn’t see me being picked up by a driver.

“I think we need to give her a chance,” said Tommy.

“Do we have a choice?” I inquired, and Trey, who’d been looking at his BlackBerry again, shook his head and said, “We do not.”

I sighed. Tommy finished his cigarette. Trey put his telephone back in his pocket. “Dad knows enough to be careful.”

I didn’t answer. My brothers had both been away at school when my mom had left. I’d been the only one home. What happened to my dad hadn’t been dramatic. . he’d just gotten quieter and quieter, more and more pale. Prior to my mother’s departure, he was rarely home before eight o’clock at night, but, after she left, he started returning at five, then four, then three in the afternoon, locking the bedroom door behind him, saying that he needed a nap. My mother had left in September. By Christmas he’d stopped sleeping. He’d take his naps, then sit up all night by the windows, not eating, not drinking, not talking. I’d ask him, over and over, if he was all right, if he wanted anything. He’d shake his head, trying for a smile, unable to manage more than a few words. I’d talked about therapists; I’d mentioned antidepressants — half the kids I knew had been on some kind of medication for something at some point in their lives. I’d called my brothers, who’d told me — brusquely, in Trey’s case, kindly, in Tommy’s — that Dad would be fine, that this was just something he had to get through. Easy for them to say. They weren’t the ones who saw him frozen in an armchair, underneath a de Kooning on one wall and a Picasso etching on another, not noticing the art, or the sunsets over the park. They didn’t see the way his pants sagged around his shrinking waistline and flapped around his diminished legs, or the silvery stubble glinting on his chin.

One dark day in February, I came home from choir practice and found every dish in the kitchen smashed and my father shin-deep in the shards of china and porcelain. My parents had had half a dozen sets of dishes, and the mess was considerable. My father stood there, blinking, a dish with a blue bunny painted in its center in his hand. When I ran to him, I could feel the jagged edges of shattered bowls and plates and coffee cups biting at my ankles, ripping at my tights. “Daddy?”

He gave me a wavering smile. “I. . well. That felt better. That felt pretty good.” Together, we swept up the mess, filling a dozen garbage bags with the wreckage. Things improved after that. By spring, he was, as he put it, “stepping out,” whistling as I attached cuff links to the starched cuffs of his shirt, taking women to the benefits and balls my mother used to dread.

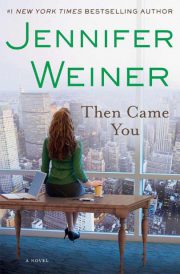

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.