Jules, India, Bettina, and Annie are such unique and distinctly defined women. As you were writing, did you find that you had a favorite character? Did you identify with one more than the others?

In this book more than any of my others, all of the characters delighted me, and all of them frustrated me. Which I think means that they’re fully realized. At least, I hope so!

The thing that I identified with most was the thing that ties the four of them together — the longing for what they don’t have; for what, in some cases, they can never have. Bettina and Jules both want their families back; India wants the promise of security, forever; Annie wants to race up the ladder of social status and be the giver instead of the taker. I think that’s universal, the desire for what you’ll never have, or had once and will never get again. Sad, but true.

In the past year, you wrote and co-produced a TV series, “State of Georgia,” which will air on ABC Family this summer. How has writing for television compared to writing a novel? Has it been difficult to go back and forth between the two mediums?

Television’s been refreshing because I have colleagues again. Turns out, I missed working with people, and being in a writers’ room is a lot of fun — you sit around with a bunch of like-minded people and make each other laugh all day long. So I like the camaraderie of television, but I also love the relative quiet of novels, where it’s just me and my thoughts and the characters, and there’s no network giving notes or saying, “Instead of casting the guy you wanted, how about this guy we like?” There’s a lot more independence with writing fiction, where you’re building a universe all by yourself…and then, of course, the excitement when you do get to work with people again — your editor, your publicist, the readers…

This is your first novel to feature a protagonist in a same sex romantic relationship. Did you know when you began writing that Jules and Kimmie would become more than friends?

I had no idea, and it really surprised me! I knew that Jules was a very closed-off, defensive, isolated character, and I knew that, in the course of the story, she’d become more open and more giving, and that the process would begin with her egg donation. I did not see Kimmie coming. Sometimes, you have to let your characters surprise you, and the two of them certainly did!

More so than your other novels, Then Came You tackles issues of class and money head on. Was this an inevitable consequence of writing about surrogacy and egg donation, or was this a deliberate decision?

One of the criticisms of chick lit that’s always bothered me is that the books don’t deal with questions of class and money — that they’re always about upper-middle-class women obsessing about their weight and soothing themselves at the mall. I think that any book about a young woman starting out in the world — first jobs, bad bosses — necessarily takes on questions of economics, whether it’s done in a comical, over-the-top way (see: Shopaholic) or a very poignant, realistic way (see: Free Food for Millionaires).

With Then Came You, I wanted to look at how larger questions of financial inequities inform the process of having a baby by surrogate — how it’s always women of means hiring less-well-off women to perform a physical task; how it is, at its core, a transactional relationship that sometimes morphs into a friendly or even familial one. I’m interested in questions of how people treat each other, and how money, and guilt over having it, or resentment over not having more, comes into play. I loved exploring India’s ambivalence at hiring a woman to do something she couldn’t do, and Annie wondering whether India secretly resented her for being able to do the one thing that she couldn’t.

The scene with Laurena Costovya, the performance artist, and India, is such a compelling and memorable one. What was the inspiration behind this?

I saw Marina Abramovic’s installation at the Museum of Modern Art last year. She performed a piece called “The Artist is Present” where, like Laurena, she sat at a table for eight hours a day, not moving, not speaking, and looked at whoever came to sit across from her. I chose not to be one of the sitters, but I wondered whether being viewed that way would have some kind of impact…whether the people in the hot seat would feel compelled to start blurting out their deepest, darkest secrets, or if they’d feel like they were being known and seen in some ways. It reminded me of the Nietzsche quote, about how when you look into the abyss, the abyss looks into you.

Then Came You is very much about family — how the families we are born into might fail us and how the families we create might save us. Many of your previous novels have tackled this issue as well. Why is this theme so important to you?

Some author — I can’t remember who — said that fiction is born from a disordered mind’s desire to create order. I think that my fixation with “found families” comes from that place. Life is messy; the family you’re born into doesn’t always function the way you wish it would, but when you grow up you get to pick the people who you’ll spend your life with. That idea’s always comforted me, and I think it’s one that resonates with readers, who might identify with Annie, and her rivalry with her sister, or Bettina and Jules, who each wind up parenting their own parents, or India, whose family failed her so completely. There was something so satisfying about a scenario in which all of the women get a second chance, to build a better family, and I liked exploring the choices that each one of them made.

When you begin crafting a character, what tends to come first for you — their name? Personality? Physical attributes?

Usually, it’s knowing how they sound that comes first. I start hearing their voices. Then I figure out their names. Then — belatedly and badly — I come up with their physical attributes. Then my first readers point out that every woman in the book is tall and blond. Then I go back and fix it.

In the past year, you have been an outspoken critic of the New York Times Book Review for what you see as their bias towards covering “literary” versus “commercial” fiction, as well as their tendency towards reviewing books by male authors more frequently than those by women. How related are these two issues, in your mind? In the ten years since you published your first novel, have you seen any changes in the way that commercial fiction or female authors are covered by major review outlets?

Ah, yes. My ill-advised quest for equality in book reviewing, which began with a guy who does interviews about what kind of hand-sewn shirts he prefers calling me a fake populist, peaked when a quote-unquote literary novelist said I had no right to be reviewed because I “churn out” a book every year and sell them at Target (shocking!), and ended with the editor of a highbrow publishing house making fun of my made-up German in the New York Times. What a fun-filled few months it was.

Honestly, it seemed like such a basic thing to point out: the Timesreviews bestselling mysteries and thrillers and genre books that men read and write. Shouldn’t the paper of record cover genre fiction written by and for women, too? Turns out, the answer is “no!” And also, the answer is “ur boox suck!” And that was just what I was hearing from my family. Being a standard-bearer? Not a lot of fun.

All kidding aside, there’s two issues. One is that genre fiction by women does not get the attention that genre fiction by men does. The second, in my mind related concern, is that literary fiction by women does not get the attention that literary fiction by men does. A woman can write a brilliant literary book, get two great reviews, and maybe, like Mona Simpson, get profiled in the Times’ Styles section, where much will be made about her apparel and her hairstyle. A man can write a brilliant literary book, and the double review is only the beginning — there’s the long, loving magazine profile (the Sunday TimesMagazine rarely writes up female authors, and, when it does, instead of the warm embrace, they are held at arm’s length—“The Strange Fiction of Suzanne Collins,” anyone?), the op-ed pieces and book reviews he’ll be asked to contribute, the talk shows and magazine covers he’ll end up on.

After Jodi Picoult and I raised the issue, Slate ran the numbers and found that of the 545 books reviewed between June 29, 2008 and August 27, 2010, 62 percent were by men. Of the 101 books in that period that were reviewed twice, a whopping 71 percent were written by men. A few months later, an organization named VIDA did a study revealing that the ratio of men to women published was even worse in literary magazines and quarterlies like The New Republic and The Paris Review (edited by Mr. Made-to-Measure. Who was quickly profiled in the Times).

The depressing part is that, even after bestselling female authors pointed out the issue, even after the numbers confirmed that, yes, Virginia, there is a problem, the Times hasn’t changed…in fact, the paper seems to have dug in its heels and gotten even worse (double reviews for Elmore Leonard and John le Carre, nothing at all for Terry McMillan; feature on guy who wrote dopey self-help book The Four-Hour Work Week, no profile of Karen Russell, whose Swamplandia! has been one of the most-praised novels this year). When Jennifer Egan won the National Book Award, the Los Angeles Times decided that big news wasn’t that she’d won but that Jonathan Franzen had lost. The paper illustrated its story about Egan’s victory with a shot of Franzen, later offering the explanation that it simply couldn’t find a current shot of Egan. Because…its Internet was broken?

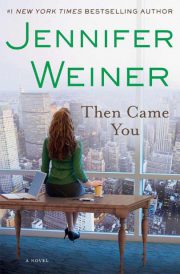

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.