Marcus sat back in his chair, his eyes unreadable. I imagined the feeling of a fishing line, formerly taut, going slack in my grip. Shit, I thought. I lost him. Then, unexpectedly, he leaned across the table and took my hands.

“I like you,” he announced. It had the tone of finality, like a manager saying you’re hired, or a groom saying I do. I felt my body uncoil. My head was humming with relief and the wine. His hands were big and warm and strong and dry — all the things you’d hope a billionaire’s hands would be. Even better, they felt no different than the hands of a man my own age, which was encouraging, because I suspected — correctly, it turned out — that his body, while well maintained, would reflect his age. Things drooped — his ass, his balls, the flabby little man-breasts that you couldn’t see underneath his made-to-measure shirts with his monogram in violet thread on the cuffs.

Marcus took me to dinners and on trips that made Kevin’s steakhouses and long weekends look like jokes. Together we went to the best restaurants and the fanciest hotels, spending long weekends in the George V in Paris and on islands you could only reach by private jet. We had tickets to the opera (I guzzled Red Bull in the ladies’ room to keep from dozing off during the arias) and invitations to museum openings and galas. I’d take him places, too, getting us tickets to events that I thought would amuse him and establish my hot-younger-woman-about-town credentials: a rock concert in a club downtown; out for a falafel, which he ate gamely, licking tahini sauce from his fingers, tucking a paper napkin on top of his tie.

His children, when I finally met them, were what I’d expected: overbred, overprivileged trust-fund brats with big white Kennedy teeth, thin lips, and suspicious eyes. One of the boys was in a band (of course, I thought to myself, keeping my smile on my face as he told me about how one of their songs was blowing up YouTube), the other boy was a lawyer working for Marcus (of course, take two), and the girl was an associate in the objet department at Kohler’s. I didn’t like the way she looked at me, narrowly, across the dinner table, then again while I was washing up (Miss Thing, of course, hadn’t bothered to clear so much as a teaspoon). I could practically read the balloon over her head, the one that said gold digger. Let her think it, I told myself. Let her imagine the worst. When it comes down to a battle between two women, whether it’s wife versus mother-in-law or girlfriend versus daughter, the woman who wins is the one he’s taking to bed.

After five dates, Marcus told me he loved me. True, he’d been having an orgasm at the time, but it still counted. I’d wiped off my mouth on his thigh and wriggled toward the headboard until I was cradled in his arms. I would never challenge him, never argue, never behave as if I was his equal. I’d be his comfort, his cheerleader, his appreciative audience, his unconditional supporter. Love you, too, I whispered, kissing his cheek, smoothing his hair off his forehead, acknowledging, to my surprise, that it almost felt like it was true.

One night in June, we went to an opening at the Museum of Modern Art. At the dinner, I was seated across from the honored guest, Laurena Costovya, a Polish performance artist in her sixties who’d come to America for a retrospective of her work. For three months, young artists would re-create some of her most famous pieces — the one where a man and a woman danced a topless tango, bashing their bodies against each other until they bled; the one where a man balanced naked on stilts for ten hours at a time, his face hidden behind an executioner’s black leather hood.

Stately as a statue at the head of the table, Laurena wore a kind of nun’s robe made of raw white silk, with her hair, still brown, in a heavy plait over one shoulder, and no makeup except for a single slash of red on her lips. When she was in her twenties, she’d carved swastikas into her belly with a shard of glass, and done installations where she’d run face-first into pillars until she collapsed. She’d lit her long hair on fire, and stood perfectly still for hours with her partner holding a switchblade to her throat, his thumb hovering over the button that would pop the knife into her neck. Here in New York, she was performing a piece entitled See/Be Seen, where she’d sit at a table for eight hours at a stretch, across from whoever cared to face her. After dinner, there was a preview. I remember the appreciative murmur as she gathered her skirts and crossed the room to take her seat. I thought about how silly the whole thing was, how far from what I thought of as “art,” as she took her seat, arranging the folds of her skirt. To me, art was a painting, a sculpture, a piece of music, not some senior citizen sitting behind a desk.

“Go on,” said Marcus, urging me toward the empty space across from the artist. I crossed the floor, heels clicking, and sat down, my smile firmly on my face, my hair swept into an updo, my makeup professionally applied (at two hundred dollars a pop it was an unwelcome expense, but I couldn’t skip it, not with photographers on hand).

Laurena regarded me. I looked back, legs crossed, hands folded in my lap. My eyes were on hers, but my mind was wandering. I was thinking about how many calories I’d consumed that day and whether the walk I’d taken at lunchtime, twenty blocks up Fifth Avenue with a circle around Bryant Park, had burned most of them off. I was wondering how soon Marcus would ask me to marry him, whether he’d ask me what kind of ring I wanted or just buy something himself, and thinking about my little apartment and whether I’d keep it, whether he’d give me the kind of allowance that would let me slip twenty-three hundred dollars to the landlord each month unnoticed, and whether there was anything besides my clothes that I’d take with me. Probably not, but I wanted to keep that apartment. It was my secret lair, my bolt-hole, my hideaway, in case I ever had to run, to go to ground. Thoughts like this were running through my head in a pleasant, lazy loop when suddenly the artist’s gaze caught me and pinned me. My face flushed, and my eyes widened. I felt as if I was being X-rayed, like my skin had been stripped off, like this woman with her plain, strong-boned face knew not only everything I was thinking but everything I was, and everything I’d done to turn myself into the woman who was sitting before her, all the parts I’d manipulated, reduced or amplified, edited and changed.

Before I could stop myself, before I knew that I even intended to speak, I found myself blurting, in a husky whisper that hardly sounded like my voice, “It wasn’t really a baby.”

Her eyes widened almost imperceptibly. The moment seemed to spin out forever. I felt my skin prickle and my mouth go dry as I sat there, trembling, every muscle tensed, waiting for. . what? For her to say something? To stand up and yell liar, or fraud? For her to proclaim, in the accented voice I’d heard on tapes of the performances she’d given, that she knew my real name? She couldn’t speak, I reminded myself. Silence was part of her shtick — her performance, to use a nicer word, but shtick was what it was. She sat. She observed. She could see and be seen, but she would never say a word.

I sat, forcing myself to hold still until my heartbeat had slowed and my legs weren’t shaking, until I was sure I had control and that no one in that well-dressed crowd had heard what I’d said. You might see things, I told the artist in my head. But I go out, I walk in the world, I do, I change. Then I gave her a smile — more of a smirk, really — and rose from the chair. With my head held high and my face composed, I crossed the enormous room, gliding over the marble floor, feeling the lights that had been set up for the taping burn against my skin. Marcus slipped his arm around my waist. “Welcome back, gorgeous,” he whispered into my ear, and I felt adrenaline surge through my body. I win, I thought. I win.

A few days later, we woke up in bed together, and I put my arms around his neck and murmured, in my sleepiest, sexiest voice, “You know, we can’t keep doing this. It’s not a good example for your children.”

“Well, then,” he said, and reached across me, opening the drawer of the bedside table and pulling out the little velvet box I’d been waiting for since I’d spotted him in Starbucks: my diamond as big as the Ritz. “I know it’s early days,” he said, his voice curiously humble, “but I’m sure about you.”

I spent three months planning a wedding — his kids, my friends, a few of his business associates and all of his assistants, who probably knew him better than any of us. Then there was the honeymoon, moving into his place, which spanned two entire stories of the San Giacomo, one of New York City’s grand old apartment buildings that stood along Central Park West. It was months before I had occasion to think of the artist again, the way she’d looked at me, the mocking curl of her lips, the way her eyes had widened as she’d stared and seemed to say without speaking, I know what you are. I know exactly what you are.

I was in the basement of T.I., one of the eating clubs on Prospect Avenue, standing in a circle of three other couples with a beer in my hand, nodding while my boyfriend Dan Finnerty talked about a hockey game. Whether this was a game he’d played in or merely a game he’d seen I wasn’t quite sure, and it was too far into the conversation to interrupt and ask him, so I nodded and smiled and laughed when laughter seemed required. When my telephone buzzed in my pocket, I tried not to look too eager as I grabbed for it.

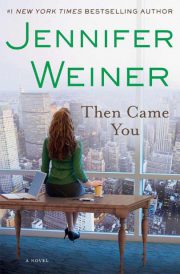

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.