One week later, Emily left work at the Beverly Hills clinic. She walked out with Woodrow and the other intern, the one who’d spent three whole days in Sunshine before coming back.

Turned out she had a vicious allergy to horses.

Emily had talked in great length with Dell about it. He’d told her to stay in Los Angeles, that they’d brought Olivia back from her maternity leave for now, that they’d work it out.

He’d told her all of this before she could say a word.

Not that she knew exactly which word she would say. She had a bunch of them. Such as . . . How was Wyatt? Did he miss her?

She missed him like she’d miss a damn limb.

I’m so sorry, she’d nearly said. Please take me back . . .

But Dell had been happy for her that she was getting what she’d wanted, and . . . he was in a hurry. When he’d disconnected, she’d stared at her phone forever.

Now she swallowed the lump in her throat, the one that felt a whole lot like homesickness. She got into her car and drove. Not to her place—which was a guesthouse in the hills, a lovely little private cottage. Instead she drove herself and Woodrow into the valley, to her dad’s house.

When she let them both in, Woodrow went directly to the kitchen, to the bowl of cat food he’d already discovered was always there just begging to be poached.

Emily plopped down on the couch next to her dad. He was reading Animal Wellness and eating from a bag of baby carrots. He had a blind parakeet on one shoulder, a three-legged cat on his lap, and two geriatric dogs at his feet, all of them clueless to the real world.

“How was work?” he asked.

“Fine. You look like Dr. Doolittle.”

He looked up and narrowed his eyes on her. “Not fine.”

And not so clueless . . .

“How long is it going to take you to realize that L.A. isn’t going to work out for you?” he asked, going back to his magazine.

“Tired of me already?”

“Never.”

Woodrow came into the living room still licking his chops and hopped up onto her dad’s legs, upsetting the balance.

The parakeet squawked. The cat hissed.

And Emily would’ve sworn Woodrow smiled at the chaos. She knew he had to take his jollies where he could get them, as he wasn’t allowed free reins at work the way he’d been at Belle Haven.

And no one had made him a badge or given him a hat.

Her dad tossed his magazine aside and hugged Woodrow. “Does he like carrots?”

“He likes everything but green veggies.”

“Smart dog.” He fed Woodrow a carrot, then looked at Emily. “Talk to me.”

She sighed and leaned her head back, staring up at the ceiling.

“Truth?”

“Yeah, let’s start with that.”

“It’s not that L.A. isn’t going to work out,” she said. “It’s more that I don’t want this life anymore.” She let that sink in. “So what’s wrong with me?”

“You want a list?” he asked.

She blew out a breath. “I’ve been here a week. I get a great stipend and a cute guesthouse to live in. It’s a great practice. I’ve been given the keys to the kingdom, Dad. It’s ‘the life’ on my plan. I go to work and if there’s no smog, I can see all of the city of Los Angeles, and yet all I can think about are the mountains.”

“I’m more of a desert man myself,” he said conversationally.

“Dad. I’m serious.”

“Me too.”

She turned her head and looked at him. “Two months ago this was all I ever wanted. It’s everything . . .” She shook her head. “But it’s not.”

He arched a brow. “Quite an admission, coming from you.”

“What does that mean?”

“Life isn’t in the planning, baby. Life’s in the living.”

She stared at him. “I can’t believe you can say that to me with a straight face. With even a little bit of planning, you could’ve had everything you ever wanted. You have a degree from Tufts, for God’s sake! You could’ve worked with the best of the best but you’re here because . . . well, I don’t know why exactly.”

“Don’t you?”

“No! And then when you didn’t put any money away and Mom got sick, you were wiped out with her medical bills and couldn’t go anywhere.”

He looked around. “I like this place.”

“But Mom could’ve been the one living in the Malibu Hills—”

“And she still would’ve died,” he pointed out gently.

“Yes, but it could’ve been easier,” Emily said, throat thick, remembering those lean, awful years.

“Honey.” Her dad put his hand on hers. “You take great care of me. That’s what you do, you take care of things. People. Animals. Whatever you can. I get that. You make a plan and you go for it, blinders on.”

“You’re missing my point, Dad.”

“No, you’re missing my point. I am living my dream. I’ve got two wonderful daughters, and I’m doing the work I love, and I married the love of my life. We had a great run.”

She stared at him.

He squeezed her hand. “Do you want to know why I loved Sunshine for you? Because it wasn’t on your plan. It wasn’t even on your radar. And every time I talked to you, you sounded alive.”

She sighed. “L.A. will work out, too. Even if I did treat a purple poodle today.”

“Honey,” he said in an amused tone, but there was something else there, something behind the laughter.

She was afraid it was a little bit of horror about the purple poodle, and also the knowledge that they both knew her life wasn’t exactly going as planned, L.A. or not.

“Emily, I’m happy with my choices. Can you say the same?”

She opened her mouth, and then closed it.

“If your mom taught you one thing,” he said. “It’s to follow your heart. Always. No regrets. Yes?”

Yes. But she also knew that following her heart caused pain. So much pain. She’d watched him suffer so much when her mom had been dying, had watched him grieve . . . “I didn’t follow my heart,” she admitted. “I followed my brain.”

And her calendar.

Yeah. So many regrets.

“You can change that,” he said. “It’s not too late. It’s never too late.”

“I can’t.”

“Why?”

Because Wyatt didn’t care that she was gone. Her heart squeezed hard at that, and she rose to her feet. “I’m going to get us dinner. Thai or Mexican?”

He met her gaze but didn’t answer.

“Dad, if you say follow your heart on this, I’m going to—”

“Italian.”

“Okay, then.” She and Woodrow headed back to the car. The dog jumped in, knocking her purse to the floorboard. She had to crouch down and reach beneath the driver’s seat to gather everything—

She stared down at the napkin lying there next to her purse. It was a small square napkin with the words Sunshine Bar on it, but that wasn’t what had her heart stopping.

No, that honor went to the scrawled penmanship— horrible penmanship—that she immediately recognized as Wyatt’s. The first line read:

Dear Emily,

Don’t fucking go.

That line was crossed out.

Twice.

She stared at the words, let out a choking half laugh, half sob, and covered her mouth with a hand as she read the rest, which wasn’t crossed out.

I want you to have everything you want, even if it’s not what I want. But I can’t let what I want come before what you want.

Ever.

But. . . I want you to stay. Please stay.

Love, Wyatt

She stared at it until the words blurred.

“Honey.” Her father stood in the doorway. “Your cell phone rang and I picked up. Work wants to know if you’ll go in early tomorrow.”

She tore her gaze off the note. “No,” she said. “I can’t.”

“It’s your job,” he said.

She clutched the napkin to her chest. “My job’s in Sunshine.”

Thirty

Still sulking?” Darcy asked Wyatt.

They were in the front yard of the house, Wyatt and his two sisters. It had been a mandatory Saturday clean-the-yard day. He was on a mission to get as much done for them as he could, because he’d hired an architect and gotten a building permit on his land. It was going to happen.

Zoe understood.

Darcy, not so much. She was still pissed off at him. “I don’t sulk,” he told her. “And you’re the one barely talking to me. Even after you lied and said you wanted me to move out.”

“I get why you want your own place,” she said, ignoring this. “We cramp your style.”

“You cramp his style,” Zoe broke in. “I’m not the one who told Emily he wet the bed until he was twelve.”

“Five,” Wyatt said through his teeth. “Only until I was five.”

Darcy was lying flat on her back in the grass that was turning brown for winter, staring up at the sky. He nudged her foot with his.

She nudged back.

That she even could was a miracle, and he crouched at her side. “I’ll be only three minutes down the road,” he said.

“Maybe that’s not far enough.”

There hadn’t been much to smile at this week, but he smiled now. “You’re going to miss me. That’s why you’re being such a shithead.”

“I’m going to miss the lobster ravioli.”

“That’s not what I’m going to miss,” Zoe said.

They both looked at her.

“I miss you being happy,” she said to Wyatt.

His smile faded. When he’d first come back to Sunshine, he’d let the familiarity, the sense of community, fill him. He belonged here, and it felt right. That rightness had only grown as he’d worked at Belle Haven. Settled into friends and a routine. Hell, even living with his sisters had given him a sense of belonging.

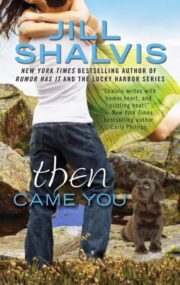

"Then Came You" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "Then Came You". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "Then Came You" друзьям в соцсетях.