In the darkness of the forest the young knight could hear the splashing of the fountain long before he could see the glimmer of moonlight reflected on the still surface. He was about to step forward, longing to dip his head, drink in the coolness, when he caught his breath at the sight of something dark, moving deep in the water. There was a greenish shadow in the sunken bowl of the fountain, something like a great fish, something like a drowned body. Then it moved and stood upright and he saw, frighteningly naked: a bathing woman. Her skin as she rose up, water coursing down her flanks, was even paler than the white marble bowl, her wet hair dark as a shadow.

She is Melusina, the water goddess, and she is found in hidden springs and waterfalls in any forest in Christendom, even in those as far away as Greece. She bathes in the Moorish fountains too. They know her by another name in the northern countries, where the lakes are glazed with ice and it crackles when she rises. A man may love her if he keeps her secret and lets her alone when she wants to bathe, and she may love him in return until he breaks his word, as men always do, and she sweeps him into the deeps, with her fishy tail, and turns his faithless blood to water.

The tragedy of Melusina, whatever language tells it, whatever tune it sings, is that a man will always promise more than he can do to a woman he cannot understand.

SPRING 1464

My father is Sir Richard Woodville, Baron Rivers, an English nobleman, a landholder, and a supporter of the true Kings of England, the Lancastrian line. My mother descends from the Dukes of Burgundy and so carries the watery blood of the goddess Melusina, who founded their royal house with her entranced ducal lover, and can still be met at times of extreme trouble, crying a warning over the castle rooftops when the son and heir is dying and the family doomed. Or so they say, those who believe in such things.

With this contradictory parentage of mine: solid English earth and French water goddess, one could expect anything from me: an enchantress, or an ordinary girl. There are those who will say I am both. But today, as I comb my hair with particular care and arrange it under my tallest headdress, take the hands of my two fatherless boys and lead the way to the road that goes to Northampton, I would give all that I am to be, just this once, simply irresistible.

I have to attract the attention of a young man riding out to yet another battle, against an enemy that cannot be defeated. He may not even see me. He is not likely to be in the mood for beggars or flirts. I have to excite his compassion for my position, inspire his sympathy for my needs, and stay in his memory long enough for him to do something about them both. And this is a man who has beautiful women flinging themselves at him every night of the week, and a hundred claimants for every post in his gift.

He is a usurper and a tyrant, my enemy and the son of my enemy, but I am far beyond loyalty to anyone but my sons and myself. My own father rode out to the battle of Towton against this man who now calls himself King of England, though he is little more than a braggart boy; and I have never seen a man as broken as my father when he came home from Towton, his sword arm bleeding through his jacket, his face white, saying that this boy is a commander such as we have never seen before, and our cause is lost, and we are all without hope while he lives. Twenty thousand men were cut down at Towton at this boy’s command; no one had ever seen such death before in England. My father said it was a harvest of Lancastrians, not a battle. The rightful King Henry and his wife, Queen Margaret of Anjou, fled to Scotland, devastated by the deaths.

Those of us left in England did not surrender readily. The battles went on and on to resist the false king, this boy of York. My own husband was killed commanding our cavalry, only three years ago at St. Albans. And now I am left a widow and what land and fortune I once called my own has been taken by my mother-in-law with the goodwill of the victor, the master of this boy-king, the great puppeteer who is known as the Kingmaker: Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, who made a king out of this vain boy, now only twenty-two, and will make a hell out of England for those of us who still defend the House of Lancaster.

There are Yorkists in every great house in the land now, and every profitable business or place or tax is in their gift. Their boy-king is on the throne, and his supporters form the new court. We, the defeated, are paupers in our own houses and strangers in our own country, our king an exile, our queen a vengeful alien plotting with our old enemy of France. We have to make terms with the tyrant ofYork, while praying that God turns against him and our true king sweeps south with an army for yet another battle.

In the meantime, like many a woman with a husband dead and a father defeated, I have to piece my life together like a patchwork of scraps. I have to regain my fortune somehow, though it seems that neither kinsman nor friend can make any headway for me. We are all known as traitors. We are forgiven but not beloved. We are all powerless. I shall have to be my own advocate, and make my own case to a boy who respects justice so little that he would dare to take an army against his own cousin: a king ordained. What can one say to such a savage that he could understand?

My boys, Thomas, who is nine, and Richard, who is eight, are dressed in their best, their hair wetted and smoothed down, their faces shining from soap. I have tight hold of their hands as they stand on either side of me, for these are true boys and they draw dirt to them as if by magic. If I let them go for a second, then one will scuff his shoes and the other rip his hose, and both of them will manage to get leaves in their hair and mud on their faces, and Thomas will certainly fall in the stream. As it is, anchored by my grip, they hop from one leg to another in an agony of boredom, and straighten up only when I say, “Hush, I can hear horses.”

It sounds like the patter of rain at first, and then in a moment a rumble like thunder. The jingle of the harness and the flutter of the standards, the chink of the chain mail and the blowing of the horses, the sound and the smell and the roar of a hundred horses ridden hard is overwhelming and, even though I am determined to stand out and make them stop, I can’t help but shrink back. What must it be to face these men riding down in battle with their lances outstretched before them, like a galloping wall of staves? How could any man face it?

Thomas sees the bare blond head in the midst of all the fury and noise and shouts “Hurrah!” like the boy he is, and at the shout of his treble voice I see the man’s head turn, and he sees me and the boys, and his hand snatches the reins and he bellows “Halt!” His horse stands up on its rear legs, wrenched to a standstill, and the whole cavalcade wheels and halts and swears at the sudden stop, and then abruptly everything is silent and the dust billows around us.

His horse blows out, shakes its head, but the rider is like a statue on its high back. He is looking at me and I at him, and it is so quiet that I can hear a thrush in the branches of the oak above me. How it sings. My God, it sings like a ripple of glory, like joy made into sound. I have never heard a bird sing like that before, as if it were caroling happiness.

I step forward, still holding my sons’ hands, and I open my mouth to plead my case, but at this moment, this crucial moment, I have lost my words. I have practiced well enough. I had a little speech all prepared, but now I have nothing. And it is almost as if I need no words. I just look at him and somehow I expect him to understand everything-my fear of the future and my hopes for these my boys, my lack of money and the irritable pity of my father, which makes living under his roof so unbearable to me, the coldness of my bed at night, and my longing for another child, my sense that my life is over. Dear God, I am only twenty-seven, my cause is defeated, my husband is dead. Am I to be one of many poor widows who will spend the rest of their days at someone else’s fireside trying to be a good guest? Shall I never be kissed again? Shall I never feel joy? Not ever again?

And still the bird sings as if to say that delight is easy, for those who desire it.

He makes a gesture with his hand to the older man at his side, and the man barks out a command and the soldiers turn their horses off the road and go into the shade of the trees. But the king jumps down from his great horse, drops the reins, and walks towards me and my boys. I am a tall woman but he overtops me by a head; he must be far more than six feet tall. My boys crane their necks up to see him; he is a giant to them. He is blond haired, gray eyed, with a tanned, open, smiling face, rich with charm, easy with grace. This is a king as we have never seen before in England: this is a man whom the people will love on sight. And his eyes are fixed on my face as if I know a secret that he has to have, as if we have known each other forever, and I can feel my cheeks are burning but I cannot look away from him.

A modest woman looks down in this world, keeps her eyes on her slippers; a supplicant bows low and stretches out a pleading hand. But I stand tall, I am aghast at myself, staring like an ignorant peasant, and find I cannot take my eyes from his, from his smiling mouth, from his gaze, which is burning on my face.

“Who is this?” he asks, still looking at me.

“Your Grace, this is my mother, Lady Elizabeth Grey,” my son Thomas says politely, and he pulls off his cap and drops to his knee.

Richard on my other side kneels too and mutters, as if he cannot be heard, “Is this the king? Really? He is the tallest man I have ever seen in my life!”

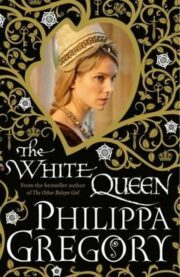

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.