“I shall stop them,” he says simply. “I shall meet them in the north of England and I shall defeat them.”

“How can you be so sure?” I exclaim.

He flashes a smile at me, and I catch my breath. “Because I have never lost a battle,” he says simply. “I never will. I am quick on the field, and I am skilled; I am brave and I am lucky. My army moves faster than any other; I make them march fast and I move them fully armed. I outguess and I outpace my enemy. I don’t lose battles. I am lucky in war as I am lucky in love. I have never lost in either game. I won’t lose against Margaret of Anjou; I will win.”

I laugh at his confidence, as if I am not impressed; but in truth he dazzles me.

He finishes his cup of ale and gets to his feet. “Thank you for your kindness,” he says.

“You’re going? You’re going now?” I stammer.

“You will write down for me the details of your claim?”

“Yes. But-”

“Names and dates and so on? The land that you say is yours and the details of your ownership?”

I almost clutch his sleeve to keep him with me, like a beggar. “I will, but-”

“Then I will bid you adieu.”

There is nothing I can do to stop him, unless my mother has thought to lame his horse.

“Yes, Your Grace, and thank you. But you are most welcome to stay. We will dine soon…or-”

“No, I must go. My friend William Hastings will be waiting for me.”

“Of course, of course. I don’t wish to delay you…”

I walk with him to the door. I am anguished at his leaving so abruptly, and yet I cannot think of anything to make him stay. At the threshold he turns and takes my hand. He bows his fair head low and, deliciously, turns my hand. He presses a kiss into my palm and folds my fingers over the kiss as if to keep it safe. When he comes up smiling, I see that he knows perfectly well that this gesture has made me melt and that I will keep my hand clasped until bedtime when I can put it to my mouth.

He looks down at my entranced face, at my hand that stretches, despite myself, to touch his sleeve. Then he relents. “I shall fetch the paper that you prepare, myself, tomorrow,” he says. “Of course. Did you think differently? How could you? Did you think I could walk away from you, and not come back? Of course I am coming back. Tomorrow at noon. Will I see you then?”

He must hear my gasp. The color rushes back into my face so that my cheeks are burning hot. “Yes,” I stammer. “T…tomorrow.”

“At noon. And I will stay to dinner, if I may.”

“We will be honored.”

He bows to me and turns and walks down the hall, through the wide-flung double doors and out into the bright sunlight. I put my hands behind me and I hold the great wooden door for support. Truly, my knees are too weak to hold me up.

“He’s gone?” my mother asks, coming quietly through the little side door.

“He’s coming back tomorrow,” I say. “He’s coming back tomorrow. He’s coming back to see me tomorrow.”

When the sun is setting and my boys are saying their evening prayers, blond heads on their clasped hands at the foot of their trestle beds, my mother leads the way out of the front door of the house and down the winding footpath to where the bridge, a couple of wooden planks, spans the River Tove. She walks across, her conical headdress brushing the overhanging trees, and beckons me to follow her. At the other side, she puts her hand on a great ash tree, and I see there is a dark thread of silk wound around the rough-grained wood of the thick trunk.

“What is this?”

“Reel it in,” is all she says. “Reel it in, a foot or so every day.”

I put my hand on the thread and pull it gently. It comes easily; there is something light and small tied onto the far end. I cannot even see what it might be, as the thread loops across the river into the reeds, in deep water on the other side.

“Magic,” I say flatly. My father has banned these practices in his house: the law of the land forbids it. It is death to be proved as a witch, death by drowning in the ducking stool, or strangling by the blacksmith at the village crossroads. Women like my mother are not permitted our skills in England today; we are named as forbidden.

“Magic,” she agrees, untroubled. “Powerful magic, for a good cause. Well worth the risk. Come every day and reel it in, a foot at a time.”

“What will come in?” I ask her. “At the end of this fishing line of yours? What great fish will I catch?”

She smiles at me and puts her hand on my cheek. “Your heart’s desire,” she says gently. “I didn’t raise you to be a poor widow.”

She turns and walks back across the footbridge, and I pull the thread as she has told me, take in twelve inches of it, tie it fast again, and follow her.

“So what did you raise me for?” I ask her, as we walk side by side to the house. “What am I to be? In your great scheme of things? In a world at war, where it seems, despite your foreknowledge and magic, we are stuck on the losing side?”

The new moon is rising, a small sickle of a moon. Without a word spoken, we both wish on it; we bob a curtsey, and I hear the chink as we turn over the little coins in our pockets.

“I raised you to be the best that you could be,” she says simply. “I didn’t know what that would be, and I still don’t know. But I didn’t raise you to be a lonely woman, missing her husband, struggling to keep her boys safe; a woman alone in a cold bed, her beauty wasted on empty lands.”

“Well, Amen,” I say simply, my eyes on the slender sickle. “Amen to that. And may the new moon bring me something better.”

At noon the next day I am in my ordinary gown, seated in my privy chamber, when the girl comes in a rush to say that the king is riding down the road towards the Hall. I don’t let myself run to the window to look for him, I don’t allow myself a dash to the hammered-silver looking glass in my mother’s room. I put down my sewing, and I walk down the great wooden stairs, so that when the door opens and he comes into the hall, I am serenely descending, looking as if I am called away from my household chores to greet a surprise guest.

I go to him with a smile and he greets me with a courteous kiss on the cheek, and I feel the warmth of his skin and see, through my half-closed eyes, the softness of the hair that curls at the nape of his neck. His hair smells faintly of spices, and the skin of his neck smells clean. When he looks at me, I recognize desire in his face. He lets go of my hand slowly, and I step back from him with reluctance. I turn and curtsey as my father and my two oldest brothers, Anthony and John, step forwards to make their bows.

The conversation at dinner is stilted, as it must be. My family is deferential to this new King of England; but there is no denying that we threw our lives and our fortune into battle against him, and my husband was not the only one of our household and affinity who did not come home. But this is how it must be in a war that they have called “the Cousins’ War,” since brother fights against brother and their sons follow them to death. My father has been forgiven, my brothers too, and now the victor breaks bread with them as if to forget that he crowed over them in Calais, as if to forget that my father turned tail and ran from his army in the bloodstained snow at Towton.

King Edward is easy. He is charming to my mother and amusing to my brothers Anthony and John, and then Richard, Edward, and Lionel when they join us later. Three of my younger sisters are home, and they eat their dinner in silence, wide-eyed in admiration, but too afraid to say a word. Anthony’s wife, Elizabeth, is quiet and elegant beside my mother. The king is observant of my father and asks him about game and the land, about the price of wheat and the steadiness of labor. By the time they have served the preserved fruit and the sweetmeats he is chatting like a friend of the family, and I can sit back in my chair and watch him.

“And now to business,” he says to my father. “Lady Elizabeth tells me that she has lost her dower lands.”

My father nods. “I am sorry to trouble you with it, but we have tried to reason with Lady Ferrers and Lord Warwick without result. They were confiscated after”-he clears his throat-“after St. Albans, you understand. Her husband was killed there. And now she cannot get her dower lands returned. Even if you regard her husband as a traitor, she herself is innocent and she should at least have her widow’s jointure.”

The king turns to me. “You have written down your title and the claim to the land?”

“Yes,” I say. I give him the paper and he glances at it.

“I shall speak to Sir William Hastings and ask him to see that this is done,” he says simply. “He will be your advocate.”

It seems to be as easy as that. In one stroke I will be freed from poverty and have a property of my own again; my sons will have an inheritance and I will be no longer a burden on my family. If someone asks for me in marriage, I will come with property. I am no longer a case for charity. I will not have to be grateful for a proposal. I will not have to thank a man for marrying me.

“You are gracious, Sire,” my father says easily, and nods to me.

Obediently I rise from my chair and curtsey low. “I thank you,” I say. “This means everything to me.”

“I shall be a just king,” he says, looking at my father. “I would want no Englishman to suffer for my coming to my throne.”

My father makes a visible effort to silence his reply that some of us have suffered already.

“More wine?” My mother interrupts him swiftly. “Your Grace? Husband?”

“No, I must go,” the king says. “We are mustering troops all over Northamptonshire and equipping them.” He pushes back his chair and we all-my father and brothers, my mother and sisters and I-bob up like puppets to stand as he stands. “Will you show me around the garden before I leave, Lady Elizabeth?”

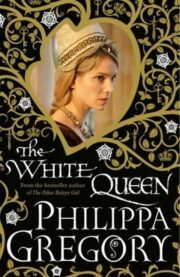

"The White Queen" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The White Queen". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The White Queen" друзьям в соцсетях.