In desperation he rode toward his capital. When he had seen Anne his faith would be restored. They would stand together; the people loved her; she was a Protestant as William was; they would prefer to see her on the throne rather than this foreigner who had no right to it while Mary and Anne lived.

But in London came the last defeat.

The Princess Anne had left hurriedly with Lady Churchill.

He knew what this meant; his daughter had deserted him.

So they are both against me, mourned James. My little girls. My Mary! My Anne!

He could see them so vividly—one dark, one fair, and he could recall his delight in them.

Charles had envied him his children and they had brought great joy to his life … when they were children and afterward.

He was a family man; the happiest times of his life, he believed, had not been when he was with his mistresses, but in the center of his family.

My daughters, he mourned, whom I loved with all my heart—and they have placed themselves among my enemies.

Mary Beatrice tried to comfort him.

“They cannot succeed,” she cried. “They are so wrong, so cruel. You are the King.”

“They do not intend that I shall remain so.”

“You think they will make William King? Never! He is not the heir. Even if they will not accept the Prince of Wales, Mary comes before him. She is your daughter. She would never agree to take your place.”

“He will set himself up with Mary. It was for this reason he married her. Would to God I had never allowed the marriage.”

“I am sure Mary will never agree to force you from your throne.”

“Mary is his creature … Anne is against me. I have lost both my daughters.”

“You have your wife,” she told him. “You have your son.”

“I bless the day you came to England.”

She closed her eyes and momentarily thought of it; the fear of this roué whom she had grown to love; the years of jealousy; and she was almost glad that he was brought so low for she was the one who could help him now; his mistresses could give him nothing but passing pleasure; she could give him unfaltering love and devotion.

“What should I do without you?” he asked.

“What should we do without each other?”

She saw that a slip of paper had been pushed under the door and withdrawing herself from his arms went to it.

It was a lampoon about the Prince of Wales having been brought to her bed in a warming pan.

She dropped it to the floor with a cry of distaste. James picked it up and read it.

“We are in danger,” he said. “You and the boy must leave England without delay.”

The Queen and the Prince of Wales had fled to France. Before the end of the year James had followed them. This was success beyond that for which they had dared hope. William was in London, and it would not be long before Mary must join him.

She was afraid.

There was no longer need to pray for William’s safety, the revolution was over. The people had accepted William, although Mary was the Queen. William’s position would depend on her, but he had no qualms; nor need he have. All that he desired should be his.

And now Mary must prepare herself for the great ordeal. What would she find on her arrival in England?

She did not want to think too much of it; yet she must make ready.

Elizabeth Villiers would make ready too. She had been calm and self-effacing during the difficult weeks, withdrawing herself from Mary’s society as much as possible. She would of course leave for England when Mary went and both of them could not help wondering what her position would be when she was there.

Would William after the long absence have forgotten his mistress? Mary believed he would; his new responsibilities would be great; and she, Mary, would be the Queen, and he the King, to rule through her grace. He would not forget that; and surely he would not insult the Queen by continuing to keep a mistress?

No, thought Mary, this would be the end of Elizabeth’s influence.

Elizabeth knew otherwise. While he lived, she was certain, he would never do without her.

She, far more than Mary, eagerly awaited the call.

Elizabeth and her sister Anne had not been on good terms since Bentinck had quarreled with William over his treatment of Mary; Anne had of course sided with her husband, which Elizabeth looked upon as treason in the family. They had tried to turn William away from her toward his own wife. She could not forgive that.

She envied Anne her children—there were five of them—and her happy married life; but of course she would not have exchanged her own lot for that of her sister, for although her position was precarious the adventure and ambition involved delighted her.

Anne had been ill for the past year; she had suffered great pain and one evening this so increased that all those about her knew she was near her end.

She asked for Mary who went to her at once and when Mary saw her friend’s condition she was horrified.

She sank on her knees by the bed and took Anne’s hand.

“My dearest friend,” she cried, “let me pray with you.”

Anne said: “If I could but see my husband …”

“Our husbands are together, Anne. I would I could bring yours to you, but he left Holland in the service of the Prince.”

“They are in England now. Oh … do you remember …?”

“I remember so much of England.”

“I am going, Your Highness …”

“Let us pray together, Anne.”

“Later. There is much I have to say. My children …”

“Do not fear for them. I will see that they are cared for.”

“I thank you. I shall go in peace since you promise me that. Commend me to my husband and the Prince …”

Mary looked up and through her tears saw Elizabeth Villiers standing some distance from the bed.

She went to her and said: “Your sister is dying. Should you not make your peace with her before she goes?”

“I do not know if that is her wish.”

Mary went back to the bed. “Elizabeth is here. She wishes to be friends. You must not die unreconciled.”

“Elizabeth …” murmured Anne.

Mary beckoned Elizabeth to come to the bed, and she stood on one side, Mary on the other.

“Elizabeth,” said Anne, “do you remember the days at Richmond?”

“I remember.”

“Come closer, so that I may see you.”

Elizabeth knelt by the bed.

“There is so much to remember … Richmond … Holland … I found great happiness in Holland. Elizabeth, you too, but you will not if …”

She was finding her breathing difficult and Mary whispered: “Rest, dear Anne. Do not disturb yourself. All is well between us all.”

The eyes of Elizabeth and Mary met across the deathbed of Anne Bentinck. Mary’s were appealing; Elizabeth’s as enigmatic as ever.

But later, when they were still there and they knew that the end was very near, Mary saw the tears silently falling down Elizabeth’s cheeks.

It was February—three months since she had said good-bye to William.

There was no excuse for a longer delay. Admiral Herbert had arrived with a yacht to take her to England. And this was good-bye to Holland; this was the end of one phase of her life. She was going to England to be a Queen and she was uneasy.

She had to take a Crown which, in truth, was her father’s; it was only because it had been forcibly taken from him that it was hers.

What would she find in England? How would the people receive an ungrateful daughter?

I shall be with William again, she told herself. What greater joy could there be for me than that?

No sooner had she stepped aboard than a storm arose and it was necessary to stay in the Maas for the rest of the day; but at last they set sail and she stood on deck watching for the first glimpse of her native land.

With what emotion she saw those cliffs; she tried to tell herself that this was the utmost joy.

Then she was aware of Elizabeth Villiers; her eyes were fixed on the approaching land with a smile as though she too were asking herself what the new life would bring, and she was confident of her future.

Mary dressed with care, for the first meeting with William. She wore a purple gown with a low bodice about which muslin was draped; her petticoat was orange velvet; there were pearls at her throat and her dark hair was piled high above her head and its darkness accentuated by the orange ribbons she wore.

She was pleased with her appearance. She looked like a Queen returning to her Kingdom. There was no hint of sadness. There must not be, for that was something which would displease William.

They were sailing up the once familiar river and there was the great city spread out before them. At Whitehall stairs William would be waiting to greet her.

There was music coming from the banks, but she kept hearing the words of a lampoon which had reached her even in Holland and she asked herself how many of those people who had clustered on the banks to watch her arrival were singing it now.

Yet worse than cruel scornful Goneril, thou;

She took but what her monarch did allow

But thou, most impious, robbest thy father’s brow.

“Father,” she murmured, “it had to be. It was for William. You are to blame … you only. It need never have been. But now it is and I fear that even if William loves me as he seemed to promise—for have I not brought him what he most desired—I shall never forget what we have done to you.”

Away melancholy thoughts!

How gay was the scene—the air bright with frost and gay with music. Cheers for the Queen who had come from Holland to rule them!

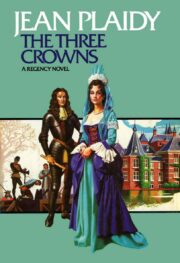

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.