“You have been a good wife to me. It is something I shall never forget.”

“And shall always be, William, in the years to come.”

“The years to come …” His expression darkened and he saw the fear leap into her eyes. Again he was satisfied.

“William, you frighten me.”

“We must be prepared for all eventualities,” he said. “I do not go in peace to your father’s kingdom. You must prepare yourself for that. And if it should please God that you should never see me again, it will be necessary for you to marry again.”

“Do not speak of it, William. Such words pierce me to the heart.”

“Then you must steel your heart, for you will be a Queen, Mary, if all goes as it must go for the sake of England and our Faith. I need not tell you that if you marry again your husband must not be a papist.”

He turned away as he spoke for the stricken expression in her eyes moved him as she had never been able to move him before.

“I give you pain by this plain speaking, I fear,” he said quietly. “But I do it only because of my strong convictions. Protestantism must be preserved in England.”

She nodded.

Then she went to him and clung to him; for some seconds he remained unresponsive then he put his arms about her and held her against him.

“I have never loved anyone but you, William,” she declared tearfully; and even as she spoke she saw the reproachful dark eyes of Frances that “dearest husband” who had remained a dear friend; she saw the jaunty ones of Jemmy and for a few revealing seconds she seemed to glimpse a different life, a life of gaiety and adventure which might have been hers if she had married him. She shut out these images. Dreams. Fantasies. Her life with William was the reality.

“William, William,” she cried, “all these years I have been married and have no child. If God does not see fit to bless me with children there would be no reason for my marrying again.”

She delighted him. This failure to produce a child she took upon herself; she did not hint as so many did that William was the one who had failed in that respect. She was a wonderful wife. Only now that he was leaving her did he realize how wonderful.

“I shall pray to God that I do not survive you, William. And if it does not please God to grant me a child by you I would not wish to have one by an angel!”

She was overflowing with her emotions, which on this occasion was pleasant.

“Your devotion pleases me, my dear wife,” said William; and Mary believed she saw a glint of tears in his eyes.

Again she clung to him and he did not resist. His kisses were warmer than they had ever been before.

“You must live, William,” she cried. “You cannot leave me now.”

“If it is God’s will,” he said, “victory will be mine. We will share the throne. God willing, there are good years ahead of us.”

They left the Honselaarsdijk Palace together and Mary accompanied him to the brink of the river and watched him embark.

Throughout Holland the people fasted as they prayed for their Prince’s victory. There was consternation when no sooner had he set out than a tempest rose which scattered his fleet and forced it to return to port.

Mary was frantic with anxiety; her doctors implored her to consider her health; but it was necessary to bleed her and it was a letter from her husband asking her to come to Brill which revived her more than any remedies.

There William spent two hours with her. He told her that there was no real disaster to the fleet and the rumors were being greatly exaggerated in England; he was going to set out immediately but he had wanted to see her once more before he left.

“Oh, William,” she cried, “how happy I am that you should spare me this time … but it only makes the parting more bitter.”

“As soon as I have succeeded in my task I shall send for you.”

She shivered slightly. She saw herself going to England, but she could only go on the defeat of her father. Her exultation in William’s response to her affection had temporarily driven everything else from her mind; but she dreaded returning to the land of her birth, for how would she ever be able to forget her childhood?

“It will not be long, I trust. And should it go against me, you will know what to do.”

He kissed her tenderly once more; and left her.

She went to the top of a tower to see the last of the fleet. Tears blinded her eyes.

It does not matter now, she thought; I can weep my fill for he is not here to be offended by my tears.

“God Save William,” she prayed. “Bring him success.”

She went back to her apartments and shut herself in to pray; but as she prayed for her husband’s success she kept seeing images of her father, and her stepmother; she kept hearing the latter’s voice appealing to her “dear Lemon” to remember her father and all his goodness to her. And she thought too of the newly-born child.

She could settle to nothing. She was continually on her knees. On waking she went to her private chapel and was again there at midday; at five o’clock she was back, and again at half past seven she attended a service.

Her prayers were all for William.

“But,” she cried to her chaplain, “what a severe and cruel necessity lies before me! I must forsake a father or forsake my husband, my country, character, and God himself. It is written Honor thy father.… But should not a wife cleave to her husband, forsaking all others?”

She wept. Never, she declared, was a woman confronted by such a cruel decision.

But her dreams came to her help. Why should not her father continue to wear the crown and William be set up as Regent? Thus her father would not be deposed; her husband would rule, and England be saved from popery.

This dream helped her through those dark days.

William had landed safely at Torbay, and the news filled James with alarm. In desperation he sought to win the approval of those whom he had offended. Catholics were not to stand for Parliament; he would support the Church of England; he would restore officials in Church and State who had lost their places due to their opposition of his will.

He appealed for support against the Dutch invasion.

But James was as ineffectual as he had ever been. It was too late to turn his coat now. There were many in the country who, while they deplored his Catholic leanings, did not approve of his son-in-law’s actions. They were asking themselves why William of Orange should be the one to take the crown which, if James and the Prince of Wales were to be dismissed, rightly belonged to his daughter Mary. There were some who did not care to see a daughter working for her father’s downfall, however much the actions of that father were to be deplored.

But James failed to see that he still had a chance.

He was concerned for the safety of his wife and the Prince of Wales; in his anxiety he was ungracious. He sent the young Prince to Portsmouth and kept his wife in London, and decided to march west and deliver a knockout blow to the forces assembled there.

His daughter Anne was popular, and he was sure he would have her support; and he would never believe that Mary, his best loved, would work against him. No, he decided, this was the work of his nephew Orange, whom he had always hated. He cursed the day he had ever agreed to that marriage in which he saw the seed of all his troubles.

He rode to Salisbury.

The shock of the invasion had been too much for him. Everyone else it seemed had been expecting it, except him. He had refused to believe the Dutch had set sail even when his trusted spies told him so; and when the fleet had been scattered he had assured himself that that was the end of the fine dreams of the Prince of Orange!

Now William was actually in England and he was marching to destroy him. At Salisbury James’s nose suddenly began to bleed so violently that he was forced to rest there before joining the army under Churchill at Warminster.

Churchill and Grafton were reckoned to be two of the finest soldiers in England. The Orange would not be able to stand up long against them.

He should be at Warminster now, conferring with Churchill, but must lie on his bed while they tried to stem the bleeding. He could rely on Churchill, who had received great good through Anne, whose great friend was Churchill’s wife, Sarah.

He had good generals; he had his dear daughters on whom he would rely, for nothing would convince him that Mary did not deplore what her husband was doing. It had been an unhappy marriage; Orange had deceived her with Elizabeth Villiers. My dear Mary, he thought, when Orange is my prisoner, when he is no longer in possession of his head, you shall tell your old father of your troubles and he will seek to make you happy.

A messenger to see the king. A messenger from Warminster!

“Show him in. Doubtless he comes from Churchill.”

“Your Majesty, Churchill is no longer at Warminster. He has left with his men …”

“Left? For what destination?”

“Torbay, Your Majesty. He is joining Orange. Grafton is with him. They have gone over to the enemy.”

James lay back on his pillows.

He saw defeat very near.

Churchill gone! Grafton gone! And there was one other. Prince George of Denmark, husband of the Princess Anne, had joined with Churchill and Grafton. They no longer served the King of England but had gone to Orange.

“There is a conspiracy in my army,” said James.

“Sire,” was the answer, “you no longer have an army.”

He must return to London, he must see his daughter at once.

She would comfort him. His dear Anne! Her husband was a traitor, even as Mary’s was; but George had always been a weak fellow, never much use.

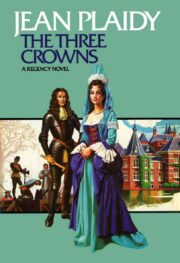

"The Three Crowns" отзывы

Отзывы читателей о книге "The Three Crowns". Читайте комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.

Понравилась книга? Поделитесь впечатлениями - оставьте Ваш отзыв и расскажите о книге "The Three Crowns" друзьям в соцсетях.